In 1994, a version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream was stolen from Oslo’s National Gallery. The thieves demanded $1m for its return. Thirteen years later, crooks broke into the Museu de Arte in São Paulo and removed paintings by Picasso and Portinari. Their ransom fee was $2m.

Clearly they had never heard of Kempton Cannon Bunton.

In 1961, the pensioner from Newcastle entered the National Gallery in London and nabbed a Goya. But it wasn’t cold hard cash he was after. His demand for its safe return was somewhat different.

Bunton was miffed. He thought it unfair that pensioners such as himself, struggling on his bus driver’s pension of £8 a week, should be forced to pay the BBC’s compulsory £4 licence fee. He had twice been imprisoned for refusing to pay. Then he heard that Francisco Goya’s 1812 Portrait of the Duke of Wellington, painted during the Peninsular war, had been purchased for £140,000 at Sotheby’s by Charles Bierer Wrightsman, an American oil entrepreneur turned art collector.

But the painting, long held by the dukes of Leeds, was considered a national treasure. It was unthinkable it might disappear across the Atlantic.

The Westminster government, aided by the Wolfson Foundation charity, matched the sale price (the equivalent of more than £3m today) to keep it in the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square.

Bunton figured if the government could stump up such a sum for a bit of paint on a canvas, it could pay the licence fee for indigent pensioners.

His attempted solution gripped the nation and beyond. On August 21, 1961, only 19 days after the painting had gone on display, it vanished. It was the first time a painting had been stolen from the gallery and Sir Philip Hendy, its director, offered his resignation (not least because embarrassing newspaper reports wrote of him luxuriating in the bath as the painting was being removed).

“You lose a Goya, then this comes out,” he said. “Makes you look a bloody fool.”

A £5,000 reward was offered for the portrait’s return. Trains, planes and ships were searched.

It seemed certain the theft was the work of a professional, a criminal aesthete at the top of his game.

Who could have gained access to the gallery with its infrared detection systems, alarms and locked doors, and walked away, even as night guards patrolled the building? A Raffles-like figure, thought some. Maybe the thief had military training, suggested others.

Except he hadn’t, and it was easy. Bunton, noting that the toilet windows always seemed to be left unlocked overnight, had chatted to gallery guards about the security system, seemingly innocently asking them how paintings were cleaned without the alarms sounding.

He learned that the system was switched off in the morning before the public was allowed in. Bunton claimed he simply climbed through the window, unhooked the Goya and left the same way, before driving to Newcastle.

Then the ransom notes started to arrive. First the news agency Reuters, then the gallery, received letters demanding a charitable payment of £140,000 for elderly people in need.

The letters accused the wealthy of loving art more than humanity and insisted the work would not be damaged or sold, all that was required was the donation.

When it was not forthcoming, the Daily Mirror was next to receive a letter. “The Duke is safe,” it read, “his temperature cared for, his future uncertain. The painting is neither to be cloak-roomed or kiosked as such would defeat our purpose and leave us open to arrest. We ask that some non-conformist type with the sportitude of a Butlin and the fearless fortitude of a Montgomery should start a fund for £140,000.”

The nation was hooked, front-page headlines covered little else. People went to see the empty space on the gallery wall. Comedian and writer Spike Milligan declared his sympathies. The story was so ubiquitous that it featured in Dr No, the first James Bond movie, released in 1962. After Bond is captured, he is seen walking through No’s underground lair. There, on an easel, is Wellington. “So there it is,” murmurs Sean Connery, in a scene guaranteed to flummox contemporary viewers of the film.

“Three pennyworth of old Spanish firewood in exchange for £140,000 of human happiness,” mused Bunton’s final note.

Then, for four years, the trail went cold until, out of the blue, the Mirror received another letter saying the painting was in a luggage locker at Birmingham New Street railway station.

And it was – rolled in a cardboard tube without its frame.

Six weeks later, on July 19, 1965, Bunton turned himself in. He had been concerned, according to his confession, that he’d “had a few beers and given too much away”. He believed somebody unscrupulous would try to claim the reward.

The painting, he said, had been behind his wardrobe. He hadn’t told his wife because he didn’t want her implicated and “all the neighbours would have known”.

Bunton, it turned out at his trial, was something of a self-educated polymath. He had written essays and plays on the condition of the working class, and penned an unpublished novel. He had a deep knowledge of political history and had read widely, even teaching himself German and French so he could read novels in their original languages.

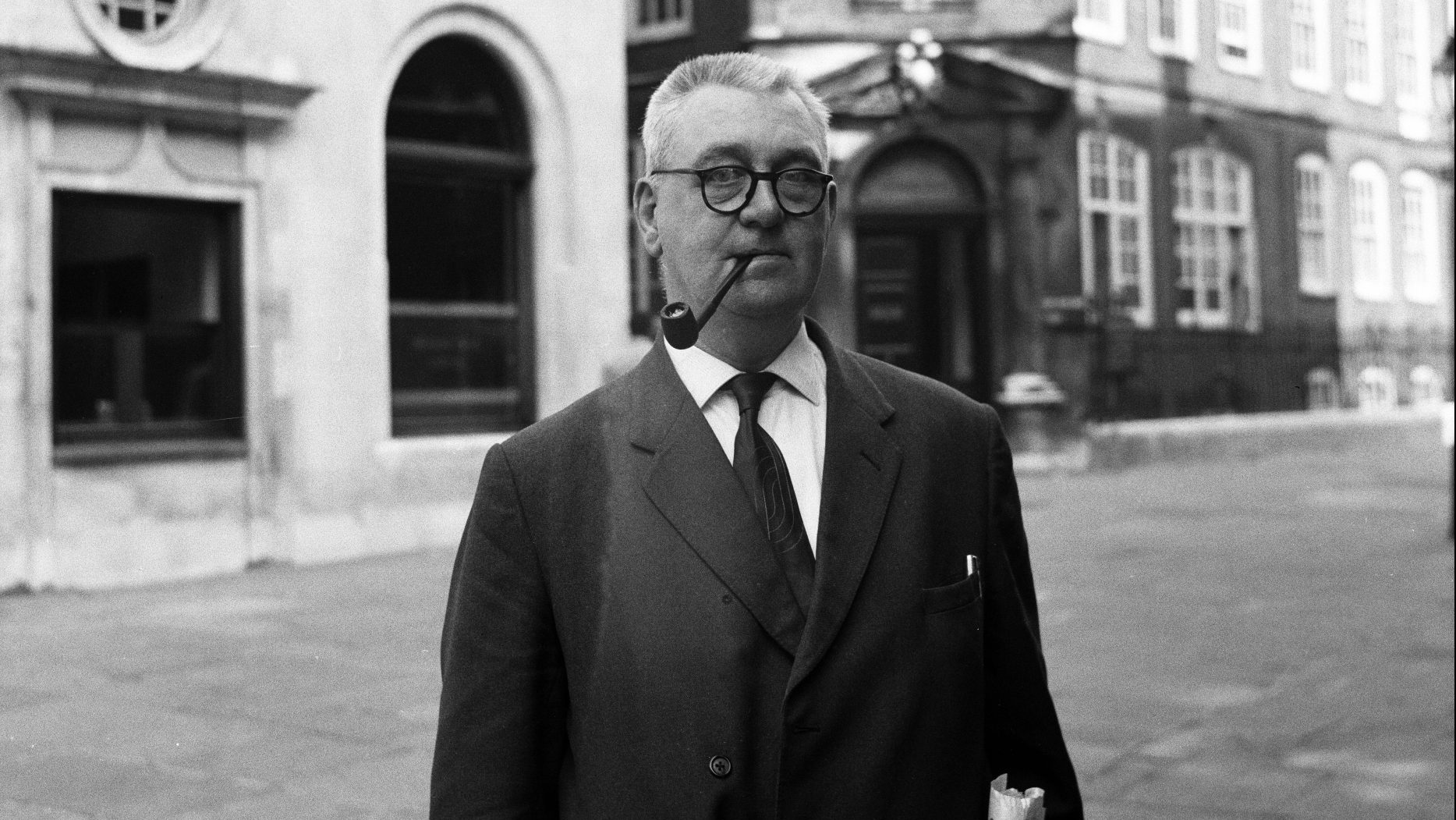

The 61-year-old grandfather emerged at his trial as the quintessential underdog, fighting for those who had little and expected less. He was lionised in the popular press as a hero, “a dreamer in a crumpled suit” for whom matters of principle were his guiding ethos and who would share his last penny and last teabag with somebody worse off than himself.

And he was acquitted of the theft of the Goya.

His legal team – led by Jeremy Hutchinson, who defended the publisher Penguin in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover case – contended that because Bunton didn’t want to keep the painting, or profit from it, he could not be convicted of stealing it. Hutchinson also argued that the painting had been described by the former president of the Royal Academy, Sir Gerald Kelly, as “incompetent and vulgar” and maybe not even painted by Goya. So didn’t Bunton have a point saying it was immoral for the government to fork out £140,000 when that could be better spent elsewhere?

But despite Bunton’s Robin Hood-esque popularity with the public, the authorities – and the trial judge – were less impressed by this warrior for social justice. The frame of the painting was never returned – Bunton said he had left it behind in London. So he got three months for the theft of the frame, the maximum for such a “crime”. And the law was changed to make it an offence to remove objects displayed in public spaces for the enjoyment of the wider populace.

His case was a cause célèbre, but here’s the kicker… it turns out it was the son wot done it. Well, maybe.

Bunton senior weighed 17st (110kg) and was registered disabled. Climbing through a small window unaided was likely to be beyond him. Not quite your usual cat burglar.

The police had mentioned it at his trial, but Bunton had confessed and the authorities were desperate to convict. However, his more lithe son, Jackie, most certainly could have slithered through the window. He would have been 20 at the time and was living in London.

In 1969, after having his fingerprints taken by police in Leeds for stealing a car, he decided to come clean, believing his dabs would have been all over the National Gallery in August 1961. Except they weren’t.

Nonetheless, released National Archive files report that the Metropolitan Police took the younger Bunton’s claims seriously, especially after he correctly described the parking metre he stood on to reach the window, determining that he probably committed the crime for which his father took responsibility. Certainly they accepted that he – and his brother Kenneth – knew about it, had helped his father to distribute the ransom notes and had taken the painting to Birmingham.

Not wanting to dredge up the case again, especially considering the anti-establishment sentiment it had roused, the Crown Prosecution Service took no further action.

Kempton Bunton died in his native Newcastle in 1976 almost unnoticed. But his wish would become reality 24 years later when TV licences were made free for the over-75s.

Of course, the world has moved on since 1961. In 2021, the level of security in public buildings would make it almost impossible for a member of the general public to walk into a gallery and steal a major work of art. The public interest, driven by more prosaic concerns, would probably pay far less attention to the story of a maverick campaigner for social justice smoking a pipe and dressed in an ill-fitting suit.

But maybe there’s an opening for another Bunton because, of course, TV licences for pensioners are once again no longer free.

It’s not something to recommend – the law has changed, remember – but if one were tempted to not steal it again, Wellington sometimes hangs in Room 39 of the National Gallery.

The Duke, a film based on the Kempton Bunton case, opens on February 25