“I waked one morning in the middle of last June from a dream, of which all I could recover was that I had thought myself in an ancient castle (a very natural dream for a head filled like mine with Gothic story), and on the uppermost banister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour,” wrote Horace Walpole in a letter to the antiquary William Cole dated March 9 1765. “In the evening I sat down and began to write without knowing in the least what I intended to say or relate. The work grew on my hands and I grew fond of it.”

Barely two months after that dream, Walpole had finished writing The Castle of Otranto, the book that spawned one of the most popular, consistent and adaptable literary genres of the last 300 years: the Gothic novel.

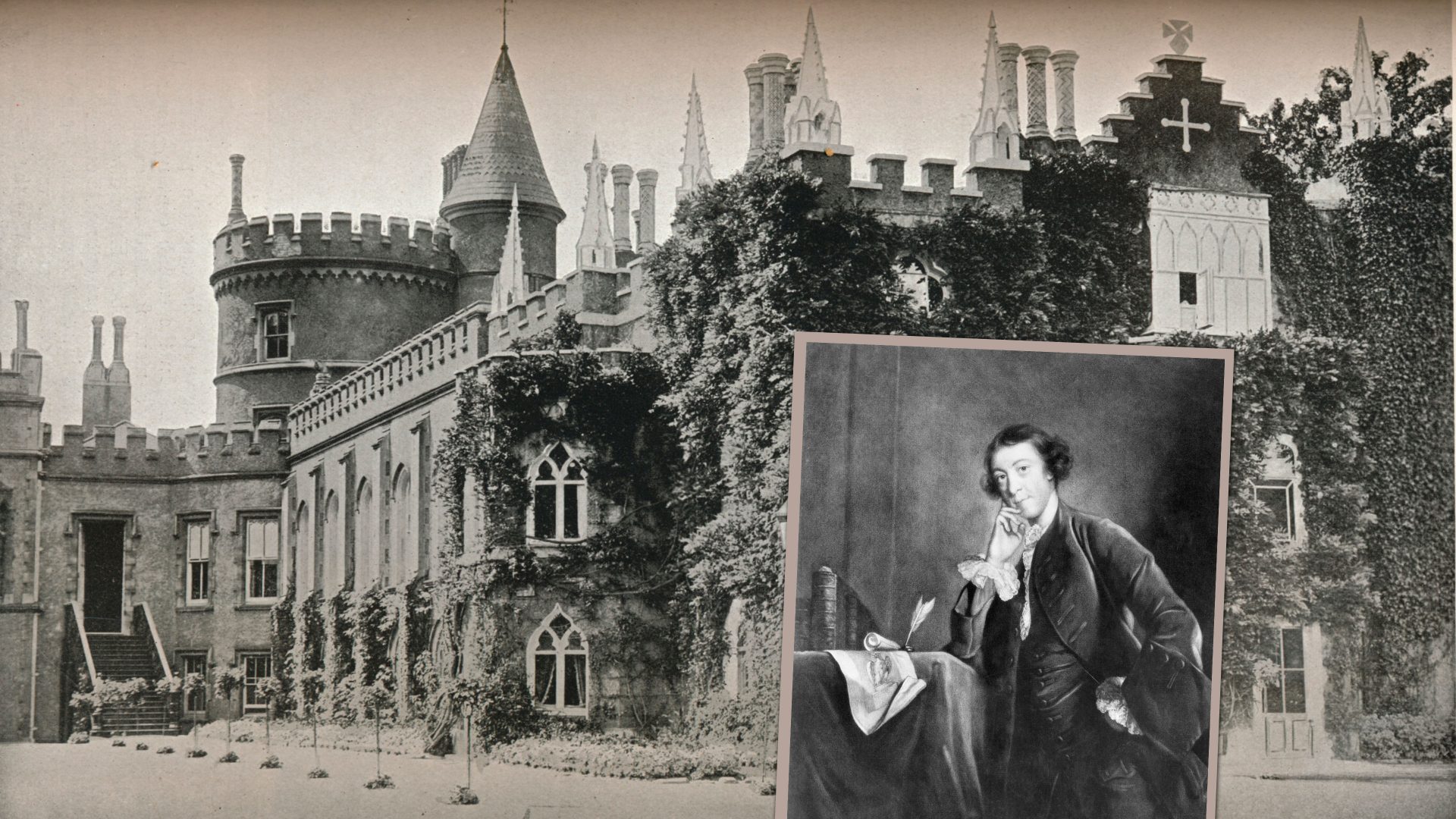

This Halloween week sees a preponderance of spooky imagery and stories, most of whose common themes and tropes can be traced back directly to one 18th-century novel written by the dilettante son of Britain’s longest-serving prime minister and a man arguably most famous for creating a preposterously ostentatious Gothic home at Strawberry Hill, near Twickenham – his deliciously overwrought tangle of spires, turrets and arches.

Written in a hurry by an author with little track record as a writer, there can’t be many books that have gone on to define a genre as thoroughly as The Castle of Otranto. Almost the entire future of Gothic fiction is already in place, fully formed: haunted castles, secret passages, ruined abbeys, clanking chains, the mournful tolling of bells in the night, thunder and lightning, dark forests, mysterious groans, skeletons, sighing portraits, secrets kept and revealed, ancient prophecies and vengeance. From Dracula to Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, from the ghost stories of MR James to The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, all spectral roads lead back to Walpole’s groundbreaking, dreaminspired European fantasy.

That’s not to say The Castle of Otranto is a brilliant book. It really isn’t. The

plot creaks like an ancient door on a rusty hinge and his characters are

superficial enough to make Liz Truss look like Simone de Beauvoir. Where it

succeeds is by rattling along at a terrific pace, keeping the reader guessing with twists and turns, some startling, some utterly ludicrous, on a rip-roaring literary voyage into fantastical excess. Otranto was the antithesis of the works based firmly in reason, realism and rationality that prevailed at the time, whopping word-thickets like Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa that made Walpole despair.

“A god, at least a ghost, was absolutely necessary to frighten us out of too much senses,” he wrote. And frighten he did: just a week after publication, his friend, poet Thomas Gray, wrote to Walpole that reading the book made “some of us cry a little, and afraid to go to bed o’nights”.

Otranto seems unsophisticated to the point of hilarity today, but its novelty and willingness to bring the supernatural into the mainstream was revolutionary for its time. Sir Walter Scott praised the book for its “happy combination of supernatural agency with human interest” as well as the excitement Walpole induced in the reader through “passions of fear and beauty”.

Nearly 60 years after its publication Lord Byron called Walpole “the Ultimus Romanorum, the father of the first romance and of the last tragedy in our language, and surely worthy of a higher place than any living writer”.

The book is set in medieval Italy where Manfred is Prince of Otranto thanks to some murderous chicanery on the part of his grandfather and is unaware of the existence of Theodore, a rightful heir to the title living as a peasant in a nearby village ignorant of his noble birth. Manfred is determined to marry off his son Conrad to Isabella, related to the genuine princely line, but on the morning of the ceremony, Conrad is killed when “an enormous stone helmet, an hundred times more large than any casque ever made for human being, and shaded with a proportionable quantity of black feathers”, lands on him from a great height. The helmet is from a statue of the man murdered to make way for Manfred’s ancestor, the evocatively named Alphonso the Good.

Intending to marry the bereaved fiancée himself to secure his position, Manfred imprisons Isabella in his castle only for her to escape to a nearby convent via a secret passage and trigger a succession of dramatic twists involving identities mistaken, unsuspected and revealed, an ancient curse, ghostly happenings in eerie locations and an ultimate happy resolution that usurps the usurpers, avenges the ancestors and satisfies the spirits.

Walpole published The Castle of Otranto on Christmas Eve 1764 but did not identify himself as the author. Instead, he claimed in a preface that the story was a translation of a document that appeared in Naples in 1529 and was found hidden in the library of a Catholic house in the north of England. The preface posits that Otranto was written sometime between the first crusade at the end of the 11th century and the last, in the 13th, the title page ascribing authorship to a priest named Onuphrio Muralto of the Church of St Nicholas in Otranto, translated by a William Marshal.

Alleged ancient provenance only served to heighten the mystery and eeriness surrounding the story, making it more plausible as a depiction of apparently true events, but when the first edition sold out in weeks after positive reviews, Walpole decided it was safe to out himself as the author.

In February 1765, just weeks after publication, he wrote to a friend of “a little story book that I published some time ago, although not boldly with my own name, but it has succeeded so well that I do not entirely any longer keep the secret”. The second edition, published that Easter with the added subtitle A Gothic Tale, identified Walpole as the author and featured a new preface explaining his intention to return the fantastic to fiction amid the contemporary tedium of realism.

“It was an attempt to blend the two kinds of romance, the ancient and the modern,” he wrote. “In the former, all was imagination and improbability: in

the latter, nature is always intended to be, and sometimes has been, copied with success. Invention has not been wanting; but the great resources of fancy have been dammed up, by a strict adherence to common life.”

The Castle of Otranto could not have happened without Walpole’s extensive

travels in Europe. The third son of Sir Robert Walpole, prime minister from

1721 to 1742, Horace was educated at Eton where he became friends with Gray, the future composer of the Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, and

Cambridge University.

Thanks to some well-compensated honorary political titles assigned to him by his father, Walpole became massively wealthy the day he turned 21. He left Cambridge without completing his degree and in March 1737 embarked with Gray on the grand tour of Europe taken by many rich young men of his era. He would be away for more than two years.

The pair made the most of Paris, then spent three months in Reims learning French, from where an excursion to Geneva left Walpole in awe of the Alps long before they became one of the touchstones of the Romantic sublime and an essential backdrop to much Gothic fiction.

“Precipices, mountains, torrents, wolves, rumblings, Salvator Rosa,” he gushed in a letter to a friend, “here we are, the lonely lords of glorious desolate prospects!”

In Italy, Walpole passed through Turin, Genoa, Bologna and dallied in Florence where he met the British envoy there, Horace Mann, whose long

residence in the city and hospitality to Grand Tourists made him a legendary

figure among travellers. While Gray busied himself among the city’s many art galleries and concert halls, Walpole preferred to indulge himself in Florentine society with Mann, causing a rift between the travellers that led to them returning home separately but producing a meeting between Walpole and aspiring architect John Chute, who would become Strawberry Hill’s “oracle of taste” in its transformation into a Gothic fantasy home.

As well as the breathtaking scenery of the Alps and the Tuscan hills, Walpole’s travels exposed him to some of the art that would fire his love of the Gothic – Rosa, Poussin, Lorrain – as well as the succession of ancient castles in various stages of decay that dotted the landscape throughout his

travels. The Castle of Otranto would be a work informed by the landscape,

history, art and culture of Europe that would change the course of the history of the novel. Walpole himself hoped it would endure, even if he

couldn’t have foreseen its extraordinary influence.

“It was not written for this age which wants nothing but cold reason,” Walpole wrote in a 1767 letter. “I wrote it in defiance of rules, critics and

philosophers and it seems to me all the better for that. I am even convinced that in some later time when taste resumes the throne from which philosophy has pushed it, that my poor castle will find admirers.”

• Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida deservedly won the Booker Prize last week. Its first review was in these pages in July, where I described it as a “wonderful book about Sri Lanka, friendship, grief and the afterlife”.