As apologies go, the one published in The Times in February 2007 was loaded with subtext. “It was not our intention to suggest, as some people may have understood it, that the Barclays frequently exploit vulnerable people in financial difficulty in an underhand and unfair way for commercial gain or to impugn their business ethics or integrity.” It did not add “nod, nod, wink, wink” but might as well have done.

Quite what the paper intended to suggest with a headline that declared: “Twins who swoop on owners in distress,” remains unclear, but the mealy-mouthed apology was sufficient to provide David and Frederick Barclay, the owners of The Telegraph, with the necessary cover to withdraw the libel action they had launched in the French courts.

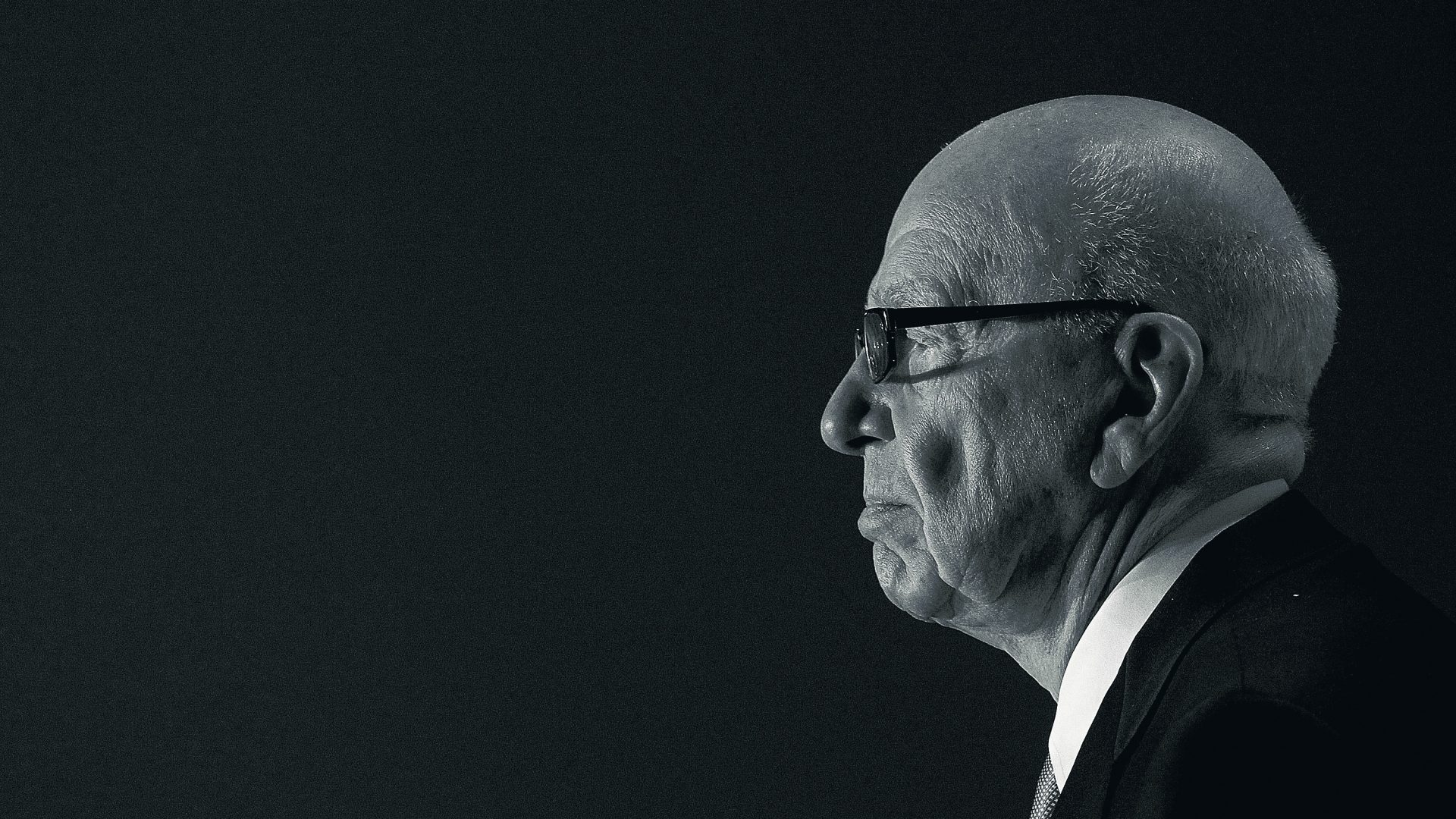

Now, in a turn of events that must be causing a degree of schadenfreude at The Times’s publisher, News Corp, The Telegraph has been snatched from the Barclay family by Lloyds Bank, as it appears that the family is unable, or unwilling, to pay the interest on loans that may be as much as £1 billion. The Telegraph, Sunday Telegraph and the Spectator magazine are now up for sale. Rupert Murdoch is – it seems – mulling a bid for the Spectator.

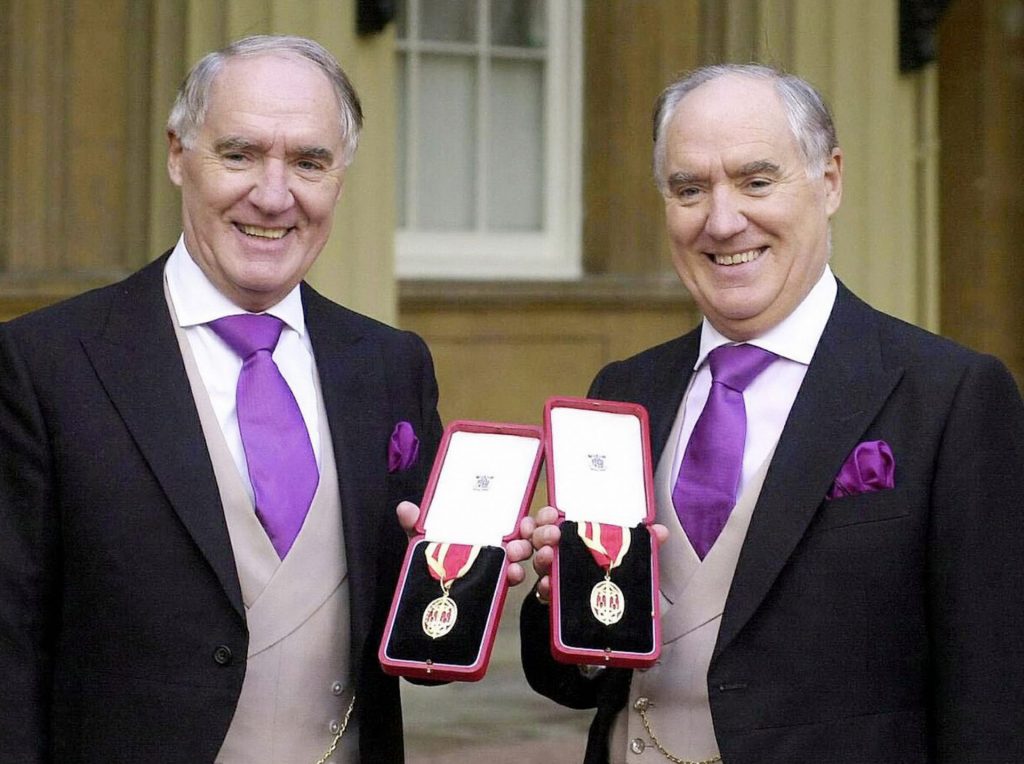

Newspaper proprietors usually stick to the unwritten code that says personal attacks on one another are off limits, so the libel spat was a highly unusual occurrence. The Barclay twins, though, did not fit the conventional mould of media magnates. Highly secretive, living in a specially built fortress on the desolate island of Brecqhou, just off Sark in the Channel Islands, they made extensive use of offshore tax arrangements – The Telegraph’s holding company of which Lloyds has now taken control is actually based in Bermuda.

The Telegraph would surely have been horrified at any British corporate leader behaving in such a way. It is, after all, a paper that upholds traditional values. Its righteous indignation over the way some MPs had milked the parliamentary expenses system kept it on its high horse for weeks in 2009, as it set out the highly-embarrassing revelations about MPs and their claims. That the information about expenses had been stolen and The Telegraph had nevertheless paid a significant sum for it was judged, probably correctly, to be justified in the public interest, although it is highly likely that the information would eventually have come to light anyway through various Freedom of Information requests. There is little doubt, though, that the manner in which the paper treated the information played a part in diminishing the public’s respect for politicians.

By the time The Telegraph was enjoying its expenses scoop, the twins had stepped back from day to day running of their various business interests, which ranged from shipping to hotels and retail as well as media, and handed the reins to the next generation of Barclay brothers, David’s sons Aidan and Howard.

The Barclay’s publishing group is more commercial than content driven, and subscriptions are now up at 750,000. The group has been at pains to point out that, despite Lloyds’ action, it generates an operating profit. There will be no shortage of potential buyers, although they may not be prepared to go as far as the £665 million the Barclays paid in 2004. Murdoch’s specific interest in the Spectator suggests that the group of titles could be broken up.

Various wits have tried to characterise newspaper readers. The brilliant authors of “Yes Minister”, Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn, allowed the hapless prime minister, Jim Hacker, to remark that “The Times is read by the people who run the country; the Daily Mail is read by the wives of the people who run the country…The Morning Star is read by people who think the country ought to be run by another country ; and The Daily Telegraph is read by people who think it is.” Although that was in 1987, there is still a ring of truth in the pithy summing up, at least of The Times and The Telegraph.

The Telegraph has always been a conservative and Conservative Party paper. Whether newspapers influence the thoughts of their readers or reflect the thoughts of their readers, the Telegraph and its audience were ardent Brexit supporters. The paper’s views chimed with those of the Barclay family, both ita senior and junior generations, and, at the crucial moment, also became those of the then Prime Minister, the Telegraph’s former high profile, and very highly remunerated, columnist, Boris Johnson.

But in recent years, the Telegraph’s reputation for good journalism, albeit from the right, has become tarnished by its increasingly extremist output. Its coverage of Covid became a continuing rant against “lockdown madness”. One headline from last November screamed that: “Pro-lockdown fanatics don’t deserve an amnesty.” Talk of transgender rights causes apoplexy at Telegraph towers, where the list of pet-hates extends from wokery, to the Civil Service “Blob” and on to the BBC.

And despite all the evidence to the contrary, the paper refuses to accept that Brexit might have been a misjudgment. “Brexit has been vindicated – and our dismal elites can’t bear to accept it,” was the way Allister Heath, editor of the Sunday Telegraph saw things as recently as April this year. The embrace and promotion of these outlandish views suggests that The Telegraph is in danger of being no longer the House journal of the Conservative Party but that of the Brexit party.

Ironically, in 1992, the Barclay family had bought The European, a paper launched in 1990 by Robert Maxwell with ambitions to be “Europe’s first national newspaper”. Maxwell had been keen on the idea of pan-European unity which flowered as the Berlin Wall came down, but he died in 1991. The Barclay brothers had obviously decided there was money to be made from media but the readership for The European did not materialise and, in 1998, it closed down.

By then, they had also bought The Scotsman, which they later sold, and Sunday Business, which was eventually folded into The Spectator.

It was the acquisition of The Telegraph from the disgraced Canadian, Conrad Black, that made the Barclays serious players in the media market. It brought them clout with the Conservative Party, which they clearly valued, and they were generous hosts to Margaret Thatcher, accommodating the former prime minister at The Ritz hotel towards the end of her life.

The family, though, continued to eschew the spotlight. Whereas the proprietor of the Evening Standard, Evgeny Lebedev, delights in having his photograph grace the paper’s pages, pictures of the Barclays had been rare. When David died in January 2021, the family took care that the details of his gravesite were kept from the public. But then their privacy was blown apart by successive legal actions, both concerning family disputes.

One involved the sale of The Ritz, which was sold to a Qatari billionaire but became a cause of friction between Frederick and his nephews whom he alleged had used sophisticated bugging equipment to record his conversations. The allegations were eventually admitted to be true and the case was settled out of court. This left some people who had been involved with the Barclays wondering how they gleaned their intelligence on other matters. I was editor of The Sunday Telegraph for a period in 2006-7. During that time, an occasional feeling of unease would sometimes encourage me to hold certain conversations outside my glass-sided office.

And then there were more personal matters – ever since their divorce in 2021, after 34 years of marriage, Sir Frederick’s former wife, Hiroko, has been trying to extract cash from him. A judge has ordered him to hand over £100 million, but he has failed to do so. For a family that is regularly referred to as “billionaires”, the hesitancy over such a sum is surprising. In theory, with assets including Yodel, the delivery company, and Very, the online shopping business, the Barclays should not be strapped for cash.

But the complicated structure of their empire, spread across various jurisdictions and using a complicated array of trusts, means it is unclear what level of debts they have amassed. Certainly, Lloyds’ apparent frustration over the failure to meet interest payments on its loans points towards a lack of ready cash.

Aidan, who, despite a public school education sometimes seems to model himself on Del Boy from Only Fools and Horses, doesn’t have the love for newspapers that, for instance, Rupert Murdoch still has. Even so, he would not have enjoyed the indignity of being ousted from his chairmanship of The Telegraph. His younger brother, Howard, a milder character who works alongside Aidan, tends to cede the floor to him – but he too has been ousted from the board.

Neither of them will have a say in who takes over The Telegraph. While the publishers of the Daily Mail would undoubtedly like to add it to their stable, the competition authorities might not allow it. Other contenders include Axel Springer, the German group that owns Politico and was a rival to the Barclays back in 2004. Two individuals with strong Telegraph history are mulling bids. The former chief executive, Murdoch MacLennan, has the advantage of being involved with the Belgian group, Mediahuis. William Lewis, a former editor of The Telegraph who spearheaded much of its online development before heading off to work for Murdoch in the US, is said to be seeking finance for a bid.

Whoever ends up buying The Telegraph and the Spectator will have a strong input into the UK’s political scene. Ofcom must ensure that whoever has the cash to win the paper also meets the definition of “fit and proper” that is required of media owners. Tory billionaires, keen to enhance their influence over government, might not clear that hurdle.