There’s a scene in Succession, the multi-award-winning TV series about a rich media family firm, which says it all about the tipping point at which America finds itself when it comes to work. After the sudden death of their founder, executives at Waystar Royco, a huge, fictional media corporation, are at risk of a hostile takeover by a Swedish tech startup, GoJo.

The people at Waystar are worried: they might lose their jobs. But they need the deal, and they fly off across the Atlantic to meet their opponents.

The atmosphere on the flight is tense. Geri, the long-suffering consiglieri, leans forward in the plush leather of the private jet to calm their nerves. “They’re Europeans,” she says. “They’re soft. Hammocked in their social security nets, sick on vacation mania and free healthcare. We’ve been raised by wolves.”

The wolfish American way of work has no statutory maternity or paternity leave, is unique among industrialised countries in linking healthcare to employment benefits, and ranks near the bottom of the league for holiday time. Americans are lucky to get 10 days off a year, including major holidays. Britain, Finland, Spain, Austria – in comparison with the US, we appear to have a “mania” for holidays.

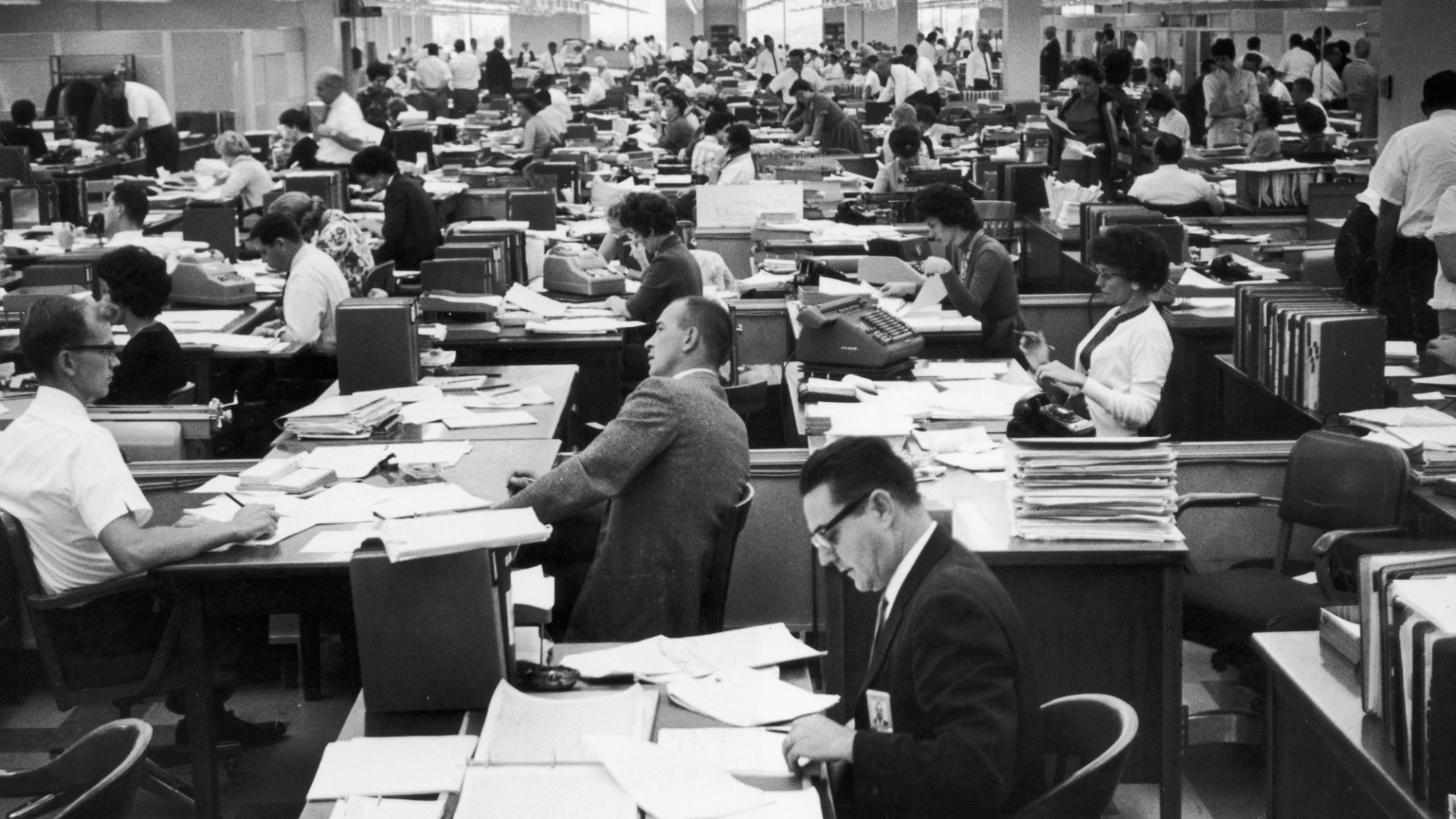

But for well over a century, the American way of work has worked. The always-in and always-on work ethic has kept it at the top of the economic tree. The largest economy in the world got there by exporting everything the rest of the world wanted – the car, the credit card, the computer, the assembly line and the internet. Indeed, the rest of the world lives and works on foundations that were born in the USA.

But the American way of work isn’t working for everyone: specifically, its own workers. Stress, including high rates of alcohol dependency and drug addiction, including mass opioid abuse, cost the US economy $300bn (£239bn) a year.

You see the toll that the American way of work takes on its workers most clearly in its popular culture, in particular its TV, movies and pop songs. Towards the end of the exhausting, adrenalin-fuelled terrorist drama Homeland, which ran to just under 100 episodes, one of the characters – a CIA officer named Saul – says wearily: “Work: it’s my Achilles’ heel”.

His colleague Carrie has a similarly troubled relationship with her job. A bipolar, workaholic spy, she can’t live with her work and she can’t live without it.

America’s Achilles’ heel has been hiding in plain sight. It can be seen in the tragi-comic conveyor belt scene from Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 movie Modern Times (which currently plays on a loop at the top of the Museum of Modern Art in New York); or in Jack Lemmon’s anguished face in The Apartment, which won best picture in 1960.

More recently, 2022’s Everything Everywhere All At Once, the first post-pandemic movie to win best film at the Oscars, was an AI-infused drama about a very American story of work: a small-time laundrette owner plagued by bureaucracy and taxes – 99% of US businesses are small. These so-called “mom and pop” businesses account for nearly half of all US employment.

Over in the big corporate world, a drama of a very different kind has been playing out, not so much a Great Resignation – people still need to work – but a Great Re-evaluation. More people now want flexible work, a symbol of a desire to live differently. It’s more affordable, financially and emotionally, and not very wolfish. Perhaps it’s a bit more European.

In the US, companies ranging from Nike to Apple to Google have been struggling to find a coherent post-pandemic policy on getting workers back into the office, let alone one that actually works. Instead, there is a lot of rather general talk of “culture” and “cohesion” rather than what people want: a decent work-life balance.

Certainly, every working person everywhere, not just in the US, can be forgiven for feeling exhausted, burnt out, struggling to process the changes that have happened since the twin shocks of Covid-19 and generative AI converged on working life in such quick succession.

The massive, Covid-induced shift to hybrid working has had a vast knock-on effect on office space, on the corporate idea of “team culture” and on city design. But at the same time, schisms have opened up between those who can and cannot work remotely. Productivity levels swing wildly about. Is it up because of remote technology, or is it down because of poor work culture?

Arguments over work are swayed by people’s political persuasion and by their age. The Flex Index, which collates data on 25,000 office locations and 100 million working people in America, shows that 82% of companies founded after the year 2000 offer flexible working, compared with 53% of those founded before. For all the corporate titans who want presenteeism, a three-year study by Bain, the consulting firm, found that flexible working policies can boost growth by a fifth.

Nowadays, just under a third of paid working hours in the US are for work done from home, and the polls consistently show that hybrid working remains a firm priority for workers. America has fallen out of love with the old patterns of work – or at least it seems to have stopped believing in them quite so much.

That has led to a certain anxiety. I was recently interviewed by a Boston radio station and asked bluntly if my approach to flexible work was designed to do anything other than undermine the economy “which already has more debt than it can handle”. I responded to this with what I believe is true of not just America but the world: workplaces cannot afford to ignore shifts in technology or the widespread desire to work differently.

It’s 50 years since the US social commentator Studs Terkel wrote Working, in which he talked of a “Monday-to-Friday kind of dying”. That sense of American drudgery has been pushed down and away, but the pandemic brought it back into the conversation. It’s no accident that during the pandemic the Netflix show most streamed by Americans was – guess what – the US version of The Office.

By contrast, in the UK the Flexible Working Act came into force in April, making “the right to request” flexible working mandatory from day one. The EU Work-Life Balance Directive has been law since 2022, and even Singapore has just followed suit with similar legislation.

In America, there are moves towards the four-day week, with senator Bernie Sanders the latest to propose a 32-hour week. That might be too inflexible, although I can see it working well in factory-floor work, and all its modern variants.

The global approach to running businesses has had to become more local, and specific, and that also goes for managing workforces. Any company or country that uses US-style business practices might need to rethink – the US is the largest corporate employer in the world beyond its own borders.

These changes are exciting and important, but I can see how they throw a spanner in the works of an entire generation of leaders brought up on a globalised diet of MBAs and other qualifications and standards.

If I sound sneery it’s because I am. There is nothing wrong with creating models or applying them, but that only goes so far because, inevitably, emerging challenges require innovation.

There are plenty of good leaders doing this – in Japan they call their flexibility policy “Work Your Way”. My friend and mentor Charles Handy, author of many business bestsellers including The Empty Raincoat, says: “We are all prisoners of our past. It is hard to think of things except in the way we have always thought of them. But that solves no problems and seldom changes anything.”

The corporate world is littered with the corpses of leaders who did not listen. BlackBerry, Blockbuster and Kodak are just three examples of 20th-century companies that rode huge technological waves, but tried to shut out the future, and failed as a result.

It’s true that hybrid work can be hard for managers to deal with, as different employees will invariably want different things – CEOs often grumble about how hard it is to implement. They have a point. White- and blue-collar jobs have always been separated by different uniforms, by the manual/clerical divide and by different working hours. And now the new hybrid workplace has created an all-new set of class divisions.

Presenteeism is political, because some people see it as a penalty, others a choice. I sat on a London tube in the summer of 2023 and listened to the primary school teachers on their way to a march demanding improved pay and conditions. “My flatmate works from home three days a week,” one said. “That doesn’t feel fair.”

You can hear the butterfly wings of chaos theory flapping. Teachers are not normally counted as remote or flexible workers – but that was before the pandemic, when day-to-day classroom teaching in schools was done in person, not remotely. Ditto medical help – it turned out that you could provide video conferencing to far-flung places that could not be accessed.

There now has to be a reason to be there in person, a reason that everyone agrees is valid, on both sides of the table – manager and worker alike. According to their annual Workforce Report, LinkedIn saw a 52.4% rise in hybrid role postings in August 2023.

This means that if you want your workforce to be physically present, you have to tell them why and you have to compensate them. Just giving people work isn’t enough.

Working Assumptions: What We Thought We Knew About Work Before Covid and Generative AI by Julia Hobsbawm is published by Whitefox