Europe has spoken and it has spoken with an ugly voice.

Four days of voting in 27 nations have produced an unequivocal outcome – the rise of the far right. Yes, mainstream parties, between them, still retain a majority. Yes, the various nativist-populist parties are split into different groupings and will fail to unite on important issues, such as Ukraine.

Yes, in some countries they had a slight setback. However, these caveats provide scant consolation.

They cannot hide an unavoidable truth – political forces that the world hoped had been dispensed with in 1945 are back on the march. In some parts of Europe, they are already governing; in others they are breathing down the necks of those struggling to govern.

The upheaval is equivalent to that caused by Donald Trump’s election and by Brexit in 2016 and – with key national elections looming – worse is set to come.

The damage is greatest in the two most powerful nations. In France, president Emmanuel Macron responded to a humiliating defeat for his Renaissance party by calling snap parliamentary elections. The risk is enormous.

Within a month, after two rounds of voting on June 30 and July 7, France could have a government led by the far-right National Rally, most likely under the 28-year-old rising star, Jordan Bardella. Marine Le Pen will bide her time until the presidential elections in April 2027.

Ever since 2022 and his previous electoral reverse, Macron has been governing without a majority in the National Assembly. Ever the Jupiterian, the man for the grand gestures, he had hoped his forays on the world stage – in the last week alone hosting the D-day 80th anniversary commemorations in Normandy, and presidents Zelensky and Biden in Paris – would have propped up his prestige. The reverse has been the case.

The situation in Germany is just as grave. In contrast to Macron, chancellor Olaf Scholz could hardly be described as relying on charisma. His Social Democrats suffered their worst performance in living memory, their demise matched by that of the other two parties in the ruling coalition; the Greens’ vote collapsed to 11% while the liberal FDP are hovering on the point of parliamentary elimination with 5%.

The victors were both the mainstream right, the Christian Democrats and the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD). Odds will have drastically shortened on the next chancellor being Friedrich Merz, a political survivor who has yanked the CDU away from the centrism of Angela Merkel towards a more traditional conservative position.

He has been unapologetic in arguing that the only way to take on the AfD is to engage on their terms, particularly on immigration and law and order (in the minds of many of their voters one and the same thing).

A series of scandals in the first six months of the year – money from Russia, spying for China and their leader suggesting that the SS weren’t so terrible – did not harm the AfD as much as some had hoped. With 16% of the vote, the AfD ended up in second place.

Their strategists are relishing the prospect of elections in three former Länder of the communist GDR in September, where they could emerge on top in one or possibly two of the states.

Another far right group, established by Sahra Wagenknecht, a former leader of the Left party, achieved just under 6%, a creditable result for a first timer, demonstrating the horseshoe effect of extreme left and right converging.

With France and Germany in turmoil, enter stage right Giorgia Meloni. As I wrote last week, she is now a pivotal figure in European politics. Everyone – from Commission president Ursula von der Leyen to the soon-to-depart Rishi Sunak to Le Pen – has been wooing her. Her decisive victory on Sunday will enhance her position within Italy and across Europe.

The radical right – far right, alt right, extreme right or however they may be described – has become a permanent fixture in the heart of European politics. The term “fringe” is redundant.

A new generation of leaders, from Meloni to Bardella, to the coming woman in Spain, the leader of the Madrid region Isabel Díaz Ayuso, are far more sophisticated and savvier than the clowns and thugs of a decade ago.

Talking of thugs, Trump may be elected again in November, but his successors will be even harder to beat as social democracy and Christian democracy founder.

For the past decade the approach of most mainstream politicians was to try to ignore the populists, to deny them “the oxygen of publicity”. In 2000, when Jörg Haider, the leader of Austria’s far right Freedom Party, joined a coalition government, the EU’s other leaders shunned the country for months.

The cordon sanitaire, or the firewall as the Germans called it, has been smashed.

Von der Leyen’s pre-election love-in with Meloni produced fury from many mainstream politicians. The SPD’s lead candidate on its parliamentary list, Katarina Barley, reiterated the pledge made by the various centre left groups to “never cooperate nor form a coalition with the far right and radical parties at any level”.

They may still hold to that promise, but the centre right has no such compunction.

Not all is gloom. In several countries of central Europe, where many voters had embraced populism in protest at economic hardship they attributed to globalisation, mainstream parties staged a small recovery.

The Smer-SD party of Slovakia’s prime minister, Robert Fico, who was nearly killed a few weeks ago in an assassination attempt, was beaten by the Progressive Left. The Fidesz party of Ur-authoritarian Viktor Orbán, may have emerged in first place in neighbouring Hungary, but the 31% achieved by a new group was remarkable.

Promising to shake up politics and combat cronyism, ally-turned-foe Péter Magyar set up his new Respect and Freedom party as recently as February. He also ended up with 31% of the vote.

Other crumbs of comfort came from the failure of the far right Flemish separatist Vlaams Belang to become Belgium’s largest party in national and European elections (held on the same day) and by strong showings for centre left and Green parties in Denmark and Sweden.

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party (which performed stunningly in recent parliamentary elections) this time came only second, while Austria’s party of the same name came out as winners, but only narrowly.

In Poland, Donald Tusk’s staunch pro-Ukraine and anti-authoritarian position held up well – which will have come as an enormous relief to Zelensky and Biden.

So, what to expect from the European Parliament? It is a sign of the times, and how habituated the world has become to the emergence of the far right, that the results across the continent were pretty much in line with opinion poll predictions.

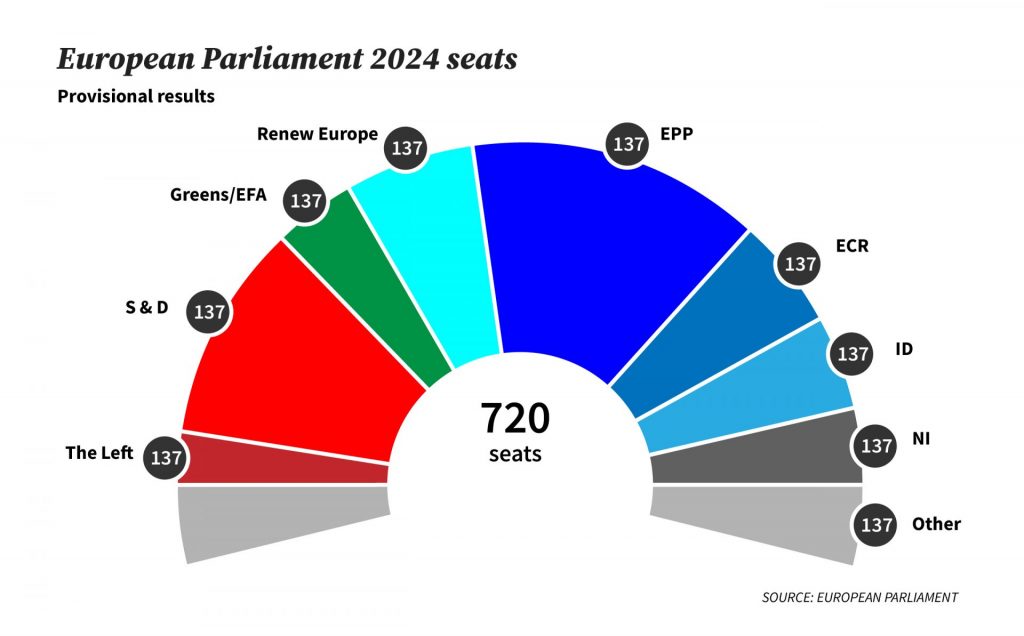

With 184 seats, the centre right European People’s Party (EPP) remains the largest force, followed by the Socialists and Democrats on 139. Even though its vote haemorrhaged, Renew Europe, the liberal grouping, is still in third place with 80.

Then come the European Conservatives and Reformists (the Meloni-style bloc) on 73, with Le Pen’s Identity and Democracy on 58.

The numbers are inexact as different groupings and individual parliamentarians jump allegiances (for example, currently the AfD and Fidesz are currently homeless).

Far more important is the overall trend. Expect more Fortress Europe on immigration. The European Union already offshores much of its refugee problem to Turkey and to countries of the Maghreb. This is almost certain to intensify.

During the election campaign, Meloni visited a former Albanian air base called Gjader, 50 miles north of the capital, Tirana. Standing alongside her host, Albania’s prime minister, Edi Rama, she promised an “extremely innovative” plan for holding centres that would process up to 3,000 migrants a month after they are intercepted at sea.

Expect also a retreat or deceleration of climate-change measures. Five years ago, a green wave in the 2019 elections spurred Europe’s leaders to pledge a radical restructuring of the economy aimed at making the EU climate-neutral by 2050.

Russia is the biggest point of division. Some parties, like Alternative for Germany (AfD), are open fans of Russian president Vladimir Putin. Others like Meloni’s Brothers of Italy or Poland’s Law and Justice party are, for reasons of conviction or convenience, among his staunchest opponents.

In just a few weeks, on July 1, Hungary takes over the six-month presidency of the EU Council. The role is not quite as crucial as it used to be – summits now largely take place in Brussels rather than a spruced-up palace provided by the host country. But the presidency is still important.

Orbán’s penchant to cosy up to Putin is long established, which is why von der Leyen and Macron have been keen to try to kickstart talks with Ukraine on EU accession as soon as possible.

The relatively strong performance of the EPP may have won von der Leyen the second term that she has so ardently sought, particularly as two of her strongest detractors, Macron and Scholz, are not in a position to put up a fight.

“The centre is holding, but it is also true that the extremes on the left and on the right have gained support,” she declared, trying to put the best possible gloss on the outcome. She will now work with whoever is prepared to work with her.

Around four in five of the current commissioners are likely to be replaced, a turnover that is relatively normal, but which can involve months of horse-trading between the various blocs.

The position of high representative (foreign minister) is potentially one of the most important and has attracted some high-profile candidates. Kaya Kallas, the current prime minister of Estonia, would provide fresh impetus to efforts to show a united front towards Ukraine camp.

Another possible is Poland’s foreign minister, Radek Sikorski, an equally strong figure in dealings with the Kremlin. He may instead be given a new post under discussion, that of defence commissioner.

Authoritarians and populists around the world, not least Putin himself, will have watched last weekend’s events in Brussels and beyond with glee. Russia has been accused of funding variously Brexit, Le Pen, Orbán, even Jacob Zuma’s new party in South Africa – anyone anywhere who can help to destabilise the existing order.

Ever since it was founded, the EU has looked to Paris and Berlin for leadership (with the odd pivot to London while the UK was a member and a serious player). That central axis is seriously weakened.

Macron is hoping that his daredevil election call could awaken the French to the dangers of Le Pen and Bardella. He is taking as his inspiration the decision by Pedro Sánchez, the Spanish prime minister, to call a snap election in 2023 after suffering a big defeat in regional polls.

That worked then, just, but it is a very big gamble. If Macron is forced to work with a hostile government, his last two and a half years will be truly grim.

Last autumn, rumours were flying in Germany that Scholz’s “traffic light” coalition might collapse. It didn’t happen because all three parties concluded they would be punished even further by voters.

This time, with a general election due by autumn 2025, the FDP and even the Greens might take a leaf out of Macron’s book and conclude they have little to lose. Politics in Berlin is about to enter a period of high turbulence. As for Scholz, his party surely couldn’t go into the next elections with him as its candidate for chancellor.

As he pinned medals on those few veterans still alive, Biden spoke movingly about the need to stand up to tyranny. He drew parallels between the second world war and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Western democracies may have begun to counter the enemy without. What they are spectacularly struggling to do is to withstand the enemy within.