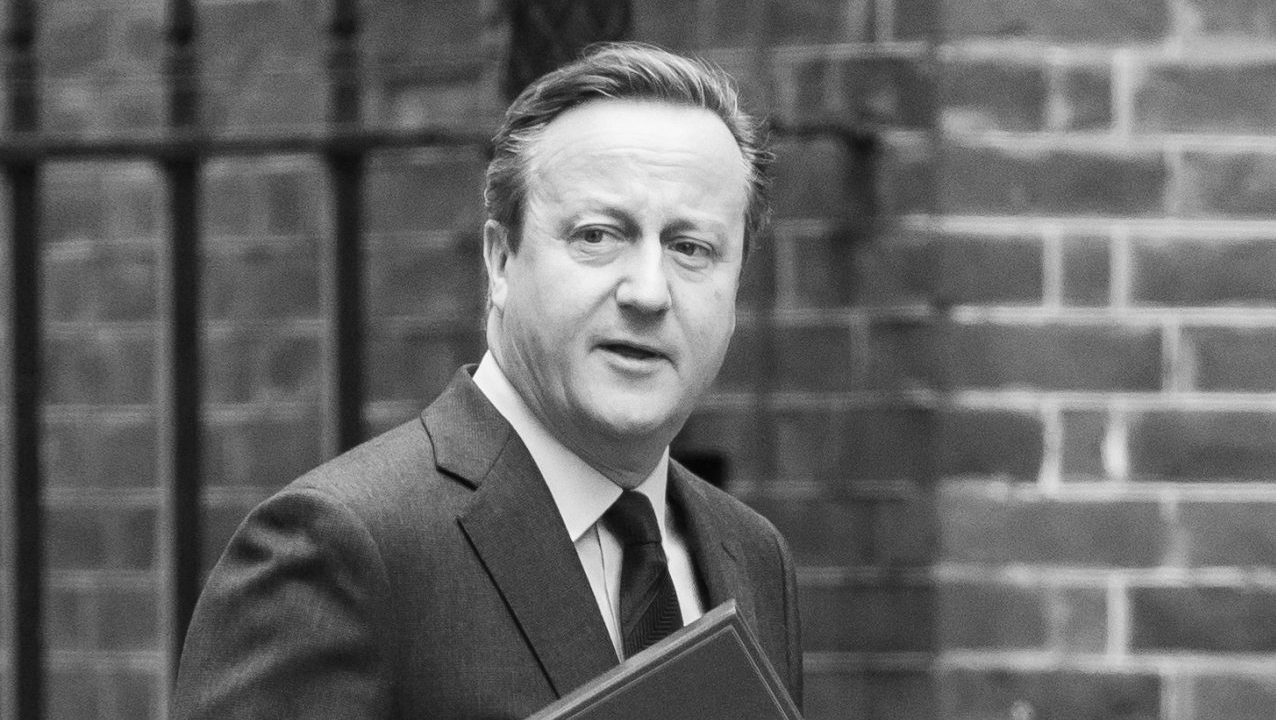

Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton sounds like a sarcastic sobriquet that Private Eye might have chosen for the former British prime minister, a snide reference to his liking for hanging out with the horsey Cotswold set. Instead, it is the title he chose on being appointed to the House of Lords in order to take on the role of foreign secretary.

He has settled into his new job with consummate ease, assuming the air of an elder statesman as he jets around the world for meetings with his international counterparts. Just how effective he has been may be a moot point, but it is arguable whether anyone representing the UK could carry a great deal of weight on the world stage, given the country’s parlous state.

Israel’s government, the focus of much diplomatic attention at the moment, has made it clear that it will do whatever prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu wants to do in Gaza, irrespective of what Cameron or others urge him to do.

Nevertheless, Cameron is at least given an audience and a degree of respect wherever he touches down.

Meanwhile, the people at the Foreign Office are said to be relieved to have at the helm someone who seems determined to be on top of his brief and work hard, despite a previous reputation for insisting on plenty of “chill-out” time.

Their positive reaction to his arrival is understandable, given that his predecessors in the last dozen years have included Boris Johnson, Dominic Raab and Liz Truss.

Cameron is not without fault. His most egregious failing was to submit to the bullying tactics of the Conservative Party’s right wing and call a referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union – and be so confident of winning that he did not orchestrate an effective campaign to ensure the result would be remain.

He was said to suffer from a degree of arrogance not uncommon among those who progress from Eton to Oxford’s notorious Bullingdon Club.

Defeat in the referendum, followed by what he saw as a need to step down from the premiership, must have been a somewhat humbling experience. The onslaught of criticism over his ill-judged involvement with the now-defunct Greensill Capital must also have been a massive blow to his ego, and the issue has the capacity still to inflict further damage on his reputation.

But Cameron is now intent on rebuilding that reputation and is making the most of the opportunity he has been given.

At this point, I should say that it was Cameron who asked me to become a member of the House of Lords. I cannot forgive him for presiding over the UK’s disastrous decision to leave the EU, nor for then leaving the way open for Boris Johnson to become prime minister. That is why I moved from the Conservatives to the Crossbench.

Nevertheless, I was pleased to see Cameron’s re-emergence on the political scene. After the chaos that has characterised British government since he left, this looked like a grown-up arriving at a children’s party.

Summoning the former PM back to government looks like one of the few good decisions that Rishi Sunak has made as prime minister, albeit Cameron was only second choice for the job, after former foreign secretary Lord William Hague turned it down.

Sunak must have looked at the available talent within his collection of Conservative MPs and concluded that a crucial role that demanded a significant personality who could carry some clout in international meetings simply could not be adequately filled from the pool available.

Any headhunter asked to fill a crucial global job from the motley collection of people Sunak leads would surely refuse, despite having to forgo the fee. Mark Menzies is just the latest Tory MP in a long line to demonstrate what appears to be total stupidity, irrespective of questionable morals.

These people are simply not equipped to deal with the hugely complicated issues that face the country.

Michael Gove, currently the secretary of state for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, memorably once remarked that the country had had enough of “experts” – but the amateurs have been a disaster.

So surely it makes sense for a sensible government to bring in all the expertise it can recruit. Cameron is an encouraging step in that direction.

When he was prime minister, Gordon Brown set about creating a “Government of All the Talents” and recruited experts in fields such as medicine and defence to take on government roles. Inevitably, they took on the acronym and were known as Goats.

But because they were made ministers, they had to be in parliament, so they were given peerages and had to perform in the House of Lords, answering questions that related not just to their area of expertise, but also to the broader remit of the department they represented. Few enjoyed the experience and most drifted away.

Now, with the drastic problems the UK is facing – whether in health, housing, productivity or social care – it is clear the country needs experts to lead programmes that will quickly deliver results. Most won’t want to be in parliament: they will be interested in achieving outcomes, not sitting in the Lords.

So why can’t they be appointed to lead a team with a specific task, within a government department? The minister they report to would be accountable to parliament for what they do, but they would be left to get on with the work.

This is what the UK needs. Lord Cameron’s appointment is not a blueprint for the future, but it is a start.