It was by far his greatest performance. At the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, Jürgen Straub ran from the front, determined to break the field before the final sprint, a brave strategy that deservedly earned him the silver medal in the men’s 1500 metres.

It was an unexpected but gritty performance and an exceptional result. First because he split the two finest middle-distance runners of their era, losing to Briton Sebastian Coe by a mere four-tenths of a second, but also defeating Coe’s countryman and rival Steve Ovett into third. But what was truly remarkable was that Straub was an East German who earned his medal without resorting to doping. Unlike most of his teammates, he ran clean.

Not so Waldemar Cierpinski, the winner of the men’s marathon, Lutz Dombrowski, winner of the men’s long jump, Bärbel Wöckel, winner of the women’s 200 metres, Ilona Slupianek, winner of the women’s shot put, or Barbara Krause, winner of the 100 and 200 metres freestyle swimming. Like the majority of East Germans who won medals that year, they were part of the most comprehensive state-sponsored sports doping system the world has ever witnessed.

In Moscow, the so-called German Democratic Republic won 47 gold medals, ranking second in the overall table, an incredible – in all senses of the word – achievement for a nation of only 17 million. That medal haul followed previous record-breaking success at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, where 40 golds were won. Eight years previously, in Mexico, they had won only nine.

From the outside, it seemed the GDR had instigated a revolution in identifying, training and supporting its athletes. Dedicated sports schools handpicked children with innate talent and – in many cases separated from parents – coaches honed their skills, so by adulthood they were ready for international competition, and ready to win.

Victorious runners, swimmers, skaters and gymnasts became the public face of their nation. The government declared their success a triumph of Marxist-Leninism, the ascendancy of communism over capitalism. What they didn’t admit was that it was actually down to cheating.

This win-at-all-costs mentality sometimes led to absurdity. At the 1976 Olympics, East German swimmers had air pumped into their colons through their anuses to improve buoyancy. “Cheating through farting,” quipped one West German newspaper. But mostly it was deadly serious.

Winning the East German way involved drugs. Lots of them. And it would come at a disturbing cost.

Children as young as 10 were recruited, most often girls because anabolic steroids and hormones such as testosterone – delivered in the form of the drug Oral Turinabol produced by the state-run pharmaceuticals company Jenapharm – had a greater impact on female performance. Steroids can shave 0.4 seconds off a female sprinter’s 100 metres time as opposed to 0.2 off a man’s. The GDR also realised other nations invested less in women’s sport, so that’s where the medals lay. Positive discrimination with malevolent motivation.

The drugs were often administered without athletes’ knowledge. Muscle mass increased, athletes could train longer and harder and recovery times were shortened. But victory had a price tag.

When their careers were over, the years of abuse began to show. Male hormones gave women deeper voices, and male hair-pattern growth. But these were minor ailments alongside early-onset liver, kidney and heart disease, infertility, miscarriage and mental health issues. And terminal cancer.

Volleyball player Katharina Bullin says: “The pills and injections were normal to me. I thought all athletes everywhere did the same. But I wasn’t aware how much I was changing. I began to be mocked, called a transvestite or a man.”

But the medals rolled in. At the World Swimming Championships in 1973 in Belgrade, the GDR’s female swimmers won 18 medals, almost half of those available. Of the 40 gold medals available to female swimmers at the Olympics of 1976, 1980 and 1988 (the GDR boycotted the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics) they won 31. They also set 127 world records between 1973 and 1989.

It was a proverbial golden era. But that gold is now tarnished. Swimmer Rica Reinisch, who was 15 when she won three titles in Moscow, says: “We were guinea pigs. And they took away from me the opportunity to ever know if I could have won without steroids.”

In later life, Reinisch has suffered miscarriages and recurring ovarian cysts. And there was little doubt, as she says, that the athletes were guinea pigs.

Joseph Tudor, author of Synthetic Medals: East German Athletes’ Journey to Hell, says: “Each athlete had a secret personalised plan where every gram of doping was weighed against a physical training programme.” But how did doctors know what dosages to prescribe? “They didn’t,” says Tudor. “In fact it was a rare and rather cruel case of human experimentation.”

The very first guinea pig was shot-putter Margitta Gummel, given 10mg of testosterone daily in the weeks preceding the 1968 Mexico Olympics. Her putting distance increased by two metres and she won gold. Scientists were then set to work across all sports where muscular intervention would improve performance.

In 1974 swimmer Birgit Meineke-Heukrodt was struggling to get results. But under coach Rolf Gläser she improved dramatically.

She was told the changes in her body, and chronic acne, were caused by the swimming pool humidity. When she discovered the truth about the “vitamin drinks” Gläser was giving her she gave up swimming. But it was too late. Meineke-Heukrodt developed liver cancer. “Why weren’t the people doing this put in prison?” she asks.

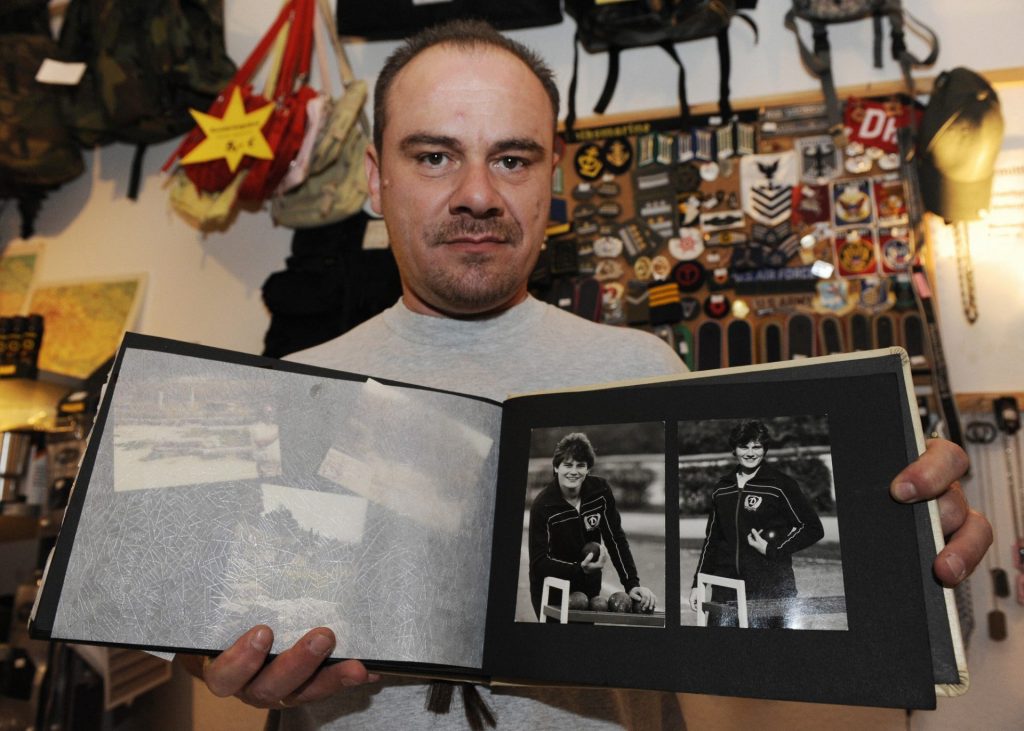

Shot-putter Heidi Krieger won gold at the European Championships in 1986, but the accretion of steroids and hormones in her body – her testosterone levels were 37 times higher than those in an average woman – had a dramatic effect. By 1997, Krieger was effectively male, through no choice of her own. She now lives as Andreas.

He carries a photograph of himself as a young girl to remind people how he looked “before they started to pump me with drugs, and unleash the hell,” he explains in Tudor’s book. Like some other female athletes, Krieger had seen his clitoris grow into a small penis.

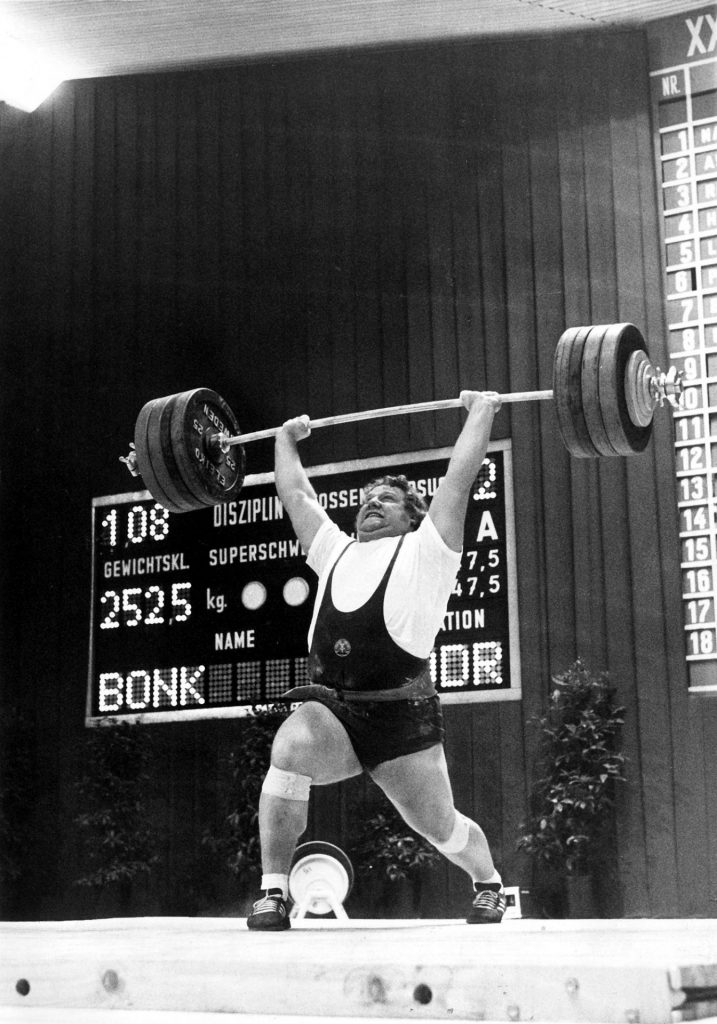

One athlete who did attest to knowingly taking steroids was weightlifter Gerd Bonk, often regarded as “the world champion of doping”. In a one-year period in the 1970s, he took 12,775mg. By comparison, the sprinter and infamous doping cheat Ben Johnson of Canada took only 1,500mg.

Bonk’s doctor, Hans-Henning Lathan, admitted he would give him untested, unapproved drugs. Even worse, Lathan knew Bonk had developed diabetes but continued to dispense new drugs without informing him.

The weightlifter’s kidneys failed, leaving him unable to walk. He died in 2014, in his words “destroyed by the GDR”.

But it wasn’t just the athletes who suffered. The baleful legacy passed to the next generation. Swimmer Martina Gottschalt’s son was born in 1984 with clubfoot, as were both children of teammate Barbara Krause. Anabolic steroids can shrink the uterus, meaning foetuses cannot grow properly.

Other athletes, their foetuses severely malformed, needed abortions, while swimmer Jutta Gottschalk’s daughter was born blind. There are hundreds, possibly thousands of other stories relating terrible outcomes. From baldness, to heart arrhythmia, mental illness to anorexia, acne to cancer, the malignancy drags on.

Although the GDR had long been suspected of running a state-sponsored programme, it was only after documents were discovered following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and then, in 1990, the confessional revelations in popular news magazine Stern by Dr Manfred Höppner, director of the sports research centre in Kreischa, that its true extent was revealed.

Staatsplanthema 14.25 began officially in 1973 and was administered by hundreds of scientists and doctors, watched over by more than 3,000 East German secret police – or Stasi – officers.

But the athletes’ suffering was not assuaged by scientists and doctors’ eventual mea culpae. They wanted retribution and remuneration. Gold medals on the mantelpiece were no recompense for heart failure, infertility and cancer.

In 2005, 160 former East German athletes sued Jenapharm, presenting evidence unearthed from the Stasi files by researchers Brigitte Berendonk and Werner Franke. The athletes were keen to emphasise that in most cases they were victims, not culprits, but even those who suspected or knew insist it was impossible to refuse.

Swimming coach Michael Regner said he was appalled to discover the women he was coaching were being given drugs without consent. “They dissolved steroids in their drinks without saying anything,” he told Der Spiegel in 1990.

Earlier hearings in the 1990s had led to some doctors and administrators receiving convictions.

Lothar Kipke, who was regarded as the architect and implementer of the programme, received a suspended sentence, which the athletes’ lawyer Michael Lehner described as “embarrassing”.

Höppner received a similar sentence, as did Manfred Ewald, the GDR’s former minister for sport. All were decried as inadequate.

Following the Jenapharm trial the athletes received compensation of €9,250 each. Considering their health problems it was paltry, somewhat alleviated in 2016 by the German government awarding a further €13.65m to be divided between all athletes deemed to have suffered under the Staatsplanthema.

But cash cannot compensate for ruined lives. Ines Geipel was a sprinter whose career was terminated when the Stasi discovered, from her own father, she was considering defecting to the west. Under the guise of an appendix operation, doctors sliced through the muscles of her abdomen, ensuring she could never compete again.

She later became honorary chair of the organisation distributing government money to former athletes, and says: “We reckon as many as 500 athletes have died because of the Staatsplanthema. Doping killed more East Germans than guards at the Berlin Wall did.”

Perhaps one of the greatest tragedies is that because the GDR took sporting endeavour seriously, with training methods, technical and performance analysis far in advance of most western nations, its athletes might have won without chemical intervention. Instead, they cheated.

“They stole my childhood, my health, my family, my trust in authority and, ultimately, they stole my life,” says Gottschalt.

It may be that Jürgen Straub too was doping – one of the lucky ones who didn’t get caught or chose not to confess. For what it’s worth, he’s not on the comprehensive list of steroid users compiled by Dr Hartmut Riedel, a leading figure in the doping programme.

Certainly there are commentators, some better informed than others, who believe everybody who entered the GDR’s athletics programme doped – it was an unavoidable obligation.

But in Straub’s favour, he never suffered the pernicious effects so many of his teammates endured, living out a healthy post-athletics life as a coach and sports-rehab physiotherapist. Aged 70, he now lives in Potsdam.

Nine years after Straub won his silver, the most extensive, most corrupt sports doping programme the world has ever seen ended when the Berlin Wall fell. But a quarter of a century later it still casts a shadow across international sport and, more tellingly, over those who participated, witting and unwitting.

Michael O’Hare is a freelance journalist, author and editor