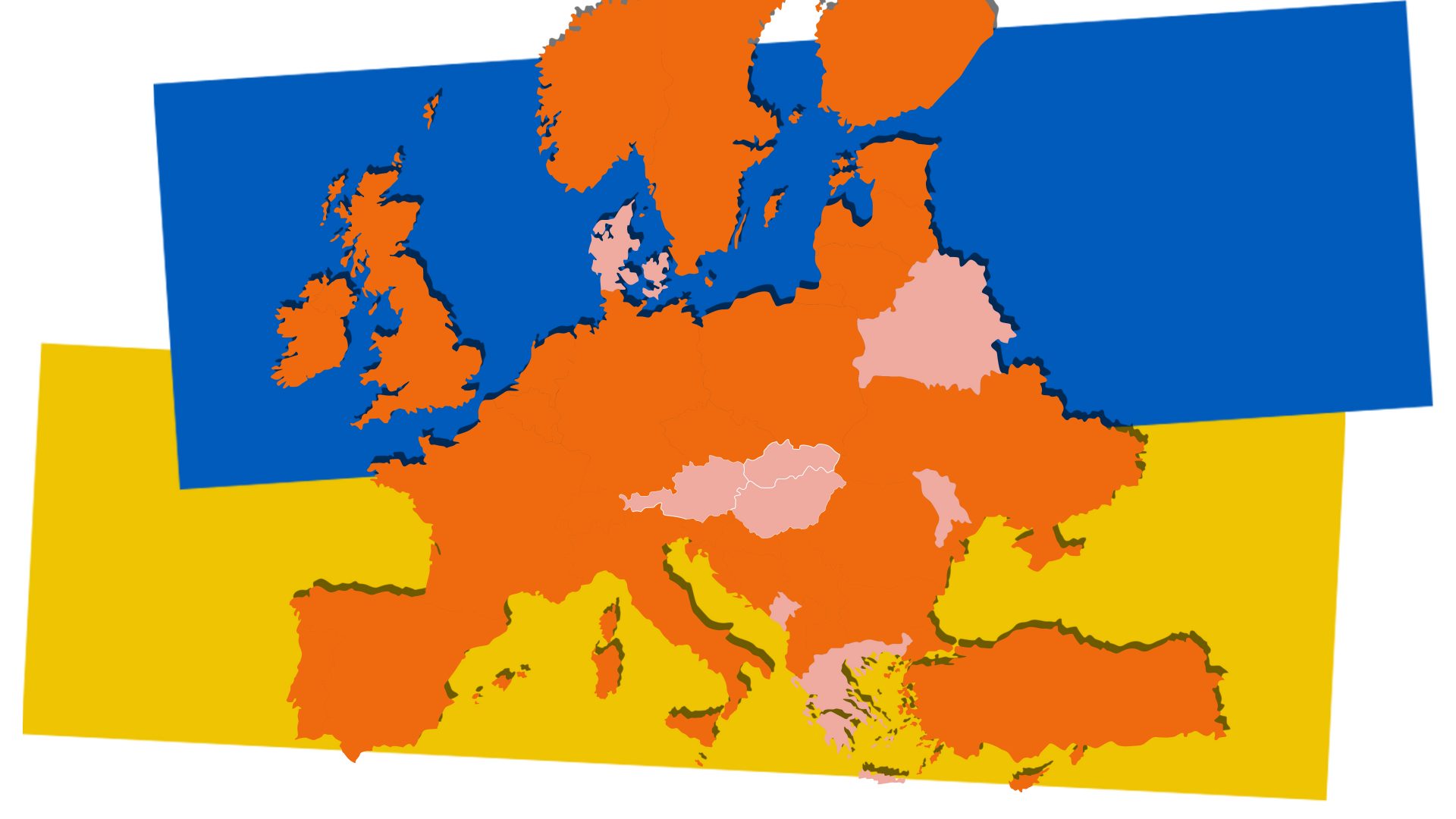

Denmark

At the Baltic Sea Energy Security Summit, held in late August in Denmark, the eight nations on the Baltic Sea agreed to restructure the region’s energy system, based on offshore wind. The leaders are planning a new distribution network between the countries of the Baltic coast, with the aim of increasing offshore power production seven-fold by 2030, and to reduce reliance on Russian gas.

Austria

Putin has always been close to Austria’s ruling elite, so close, in fact, that in 2018 he was given a personal invitation to the wedding of Austria’s then-foreign minister. After the 2014 invasion of Crimea, Putin’s first state visit was to Austria. A full 80% of Austrians are against joining Nato, and the current chancellor, Karl Nehammer, who visited Putin in April, is committed to Austrian neutrality. Austria has reduced imports of Russian gas, but attempts to act as a power broker and its continued neutrality have been criticised by both Nato and Ukraine. The country now faces a choice – follow other nations, including Sweden and Finland, and ditch neutrality, or play the mediator and risk being left out in the diplomatic cold.

Slovakia

In 2021, Putin’s approval rating among Slovaks was 55%. Now it’s less than half that figure. Slovakia has a land border with Ukraine and has registered more than 400,000 war refugees. As it does each year, Slovakia recently commemorated the anniversary of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. Eduard Heger, prime minister of Slovakia, remarked that “It is horrible, that today again, a free and democratic country faces violent occupation.” But even so, a June poll showed that only 51% of Slovaks blame Putin for the war. A substantial percentage still blame the west and Ukraine, an indication that Russian disinformation has succeeded – a challenge that the Slovakian government must confront.

Montenegro

The invasion of Ukraine has deepened divisions in Montenegro. The small nation on the Adriatic split from Serbia in 2006 and joined Nato in 2017, but remains culturally close to Serbia and Russia. Russia is the largest foreign investor in the country. In 2016, Russia tried to oust the current pro-western Montenegrin government in a coup, but failed. Now, pro-Serbian party the Democratic Front wants the country to remain neutral on Ukraine, but as a Nato member, that is not possible. Ethnic Serbs have held pro-Putin rallies, while the rock star Nikola Radunović has led anti-war counter demonstrations. The Ukraine war has given Monetenegro a political and cultural identity crisis.

Greece

Athens has tried to avoid military engagements, but Ukraine is different. Greece was one of the first nations to send arms to Ukraine, despite objections from Syriza, the opposition party, and protests from Russia, a traditional ally. There are tens of thousands of ethnic Greeks living in Ukraine, many of whom live in Mariupol, which has been terrorised by Russia. Volodymyr Zelenskyy has addressed the Greek parliament in a speech that stressed the historic links between the two countries. Greece’s stance on the Russian invasion is a historic break with Moscow.

Belarus

Back in 2020, Alexander Lukashenko was rescued by Putin when protests across Belarus nearly ended his regime. But the failure of Putin’s war and disgust at Lukashenko has stirred up Belarus’s opposition parties and encouraged a new, militant strain of anti-war activity.

Saboteurs in Belarus have attacked rail infrastructure to disrupt the movement of Russian troops across Belarus. Lukashenko has threatened these activists with the death penalty, a sign that he is rattled. Putin saved him back in 2020, but support for Putin’s war could be the beginning of Lukashenko’s end.

Hungary

Viktor Orbán is the most pro-Putin leader in Nato and the EU. Orbán condemned the invasion of Ukraine, but then argued against sanctions on Russian energy firms and oligarchs. This has allowed the Kremlin to portray the “west” as divided. Orbán’s stance is working at home and in April he won a fourth term in office. Entirely reliant on Russian energy and yet entwined in the structures of western power, Hungary could be the country that urges peace talks with Putin.

Moldova

Since the 1990s, Russia has had troops stationed in the Moldovan region of Transdniestria, there to “protect” a minority of ethnic Russians. Moldova’s army of 6,500 is too small to kick them out.

It is able to exert some influence – now that Ukraine’s border is sealed, Russia has tried to move troops and arms across from Moldova, but to Moscow’s fury, the Moldovan government said no. Moldova has deep cultural ties to Romania, an EU member, and is itself now on a fast-track to membership. But the deepest worry is that, if Putin gets his way in Ukraine, Moldova could be next.