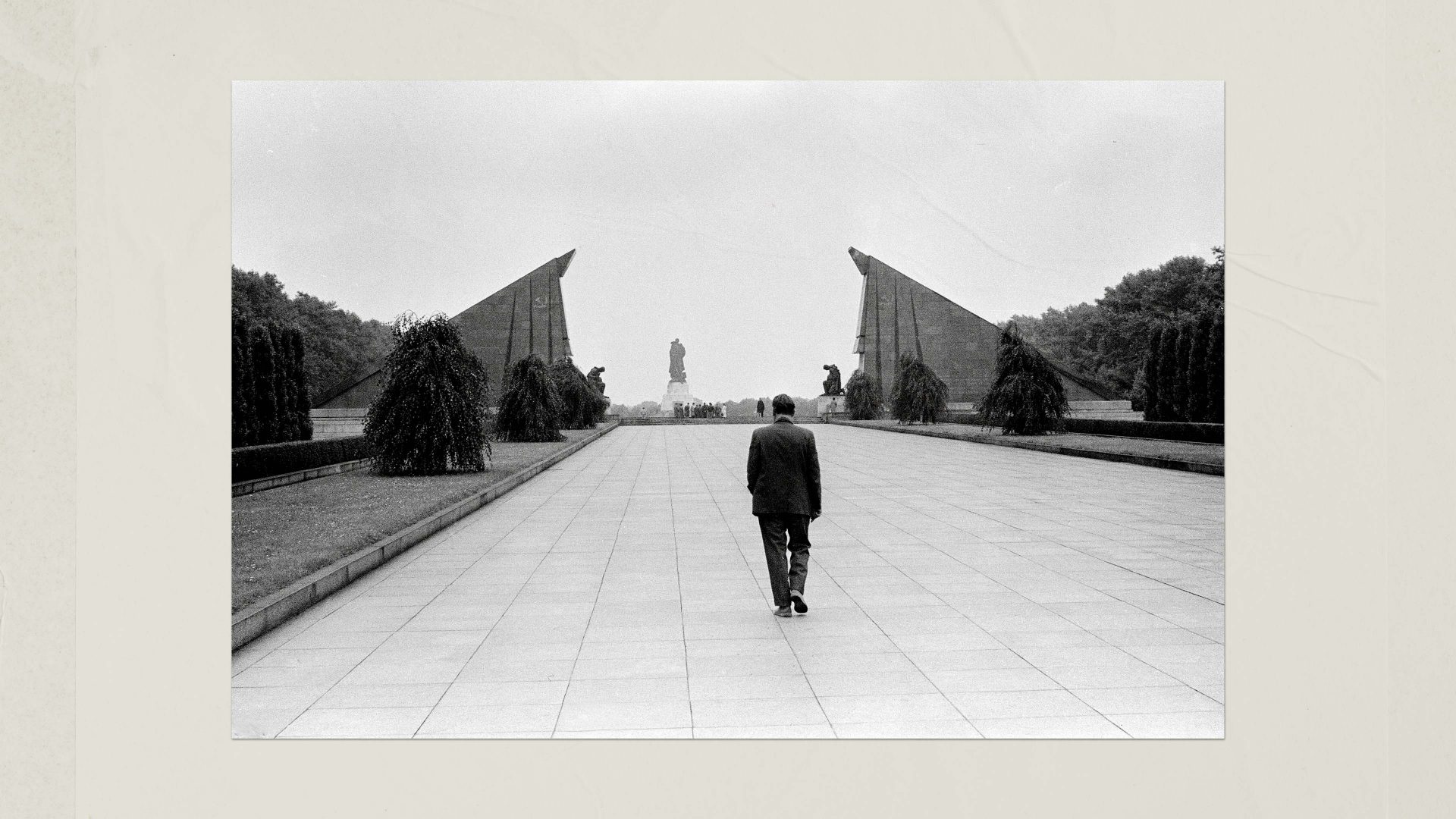

The gilded tiles that spell out the word “Glory” in Russian have been placed so that the morning light makes them shine, even on a drab day.

They lie at the centre of a mosaic at the Soviet war memorial in Treptower Park, in the east of Berlin. It is dedicated to the Red Army, which “saved the civilisation of Europe from fascist destroyers”.

The architecture is the height of Soviet military style. The visitor arrives between statues of two burly soldiers. They kneel, heads bowed in tribute to fallen comrades. Stalin’s words of praise for his troops are set in stone along the edges of the site, in Russian on one side, German on the other.

Nothing had prepared me for the way history weighs so heavily on Berlin. I had only been once before, a few years ago, passing through by train on my way to Russia. On that trip, I visited Volgograd, site of the Battle of Stalingrad, the turning point in the second world war and the starting point of the Red Army’s victorious march on Berlin. The monuments here belong to the same era and tell the same story of Soviet glory as those on the banks of the Volga.

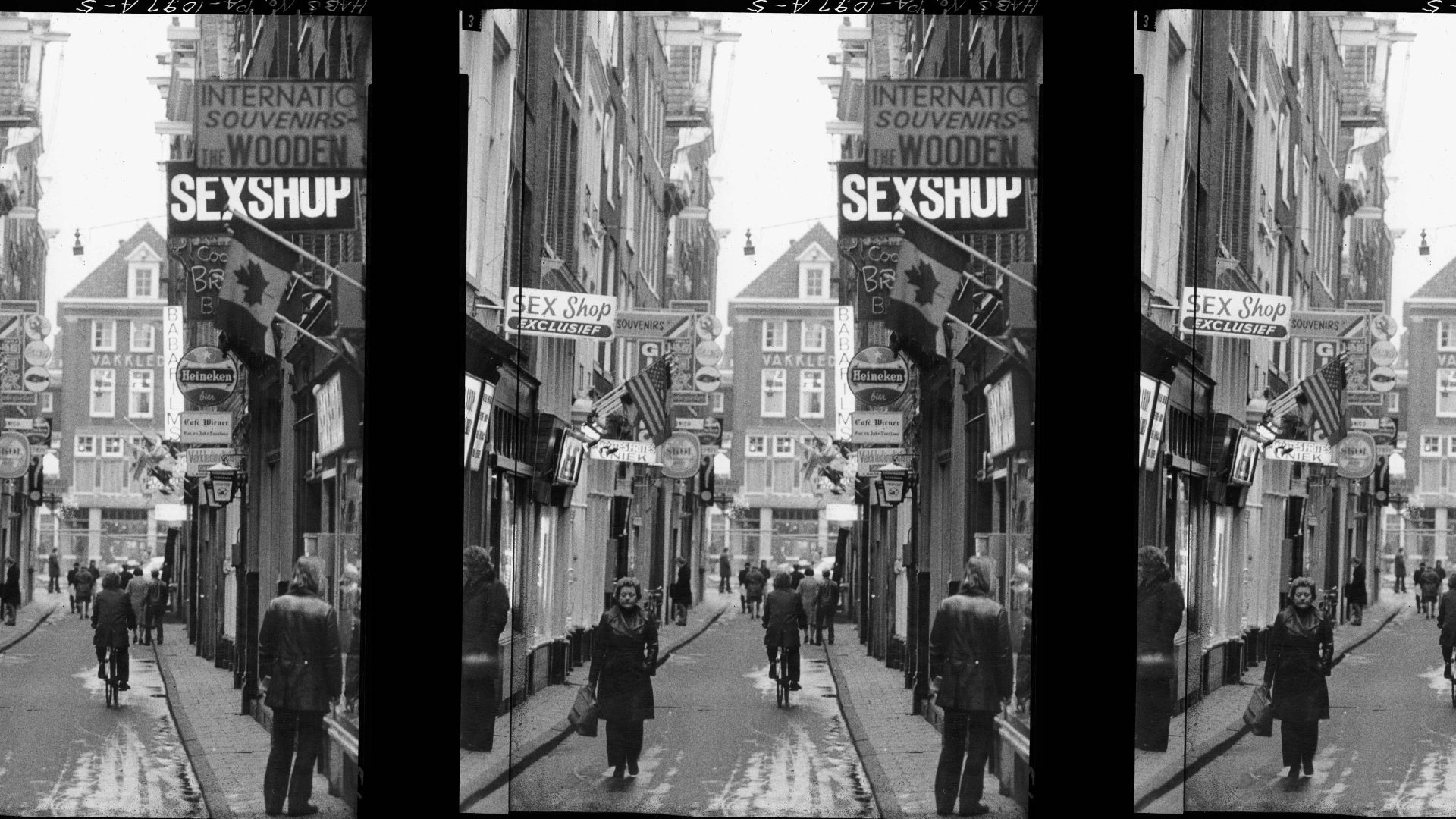

Berlin is lively, welcoming. But there are signs of the horrors of the last century – Holocaust, war, and wall – all across the city. That includes the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the Brandenburg Gate and remnants of the brickwork, watchtowers and barbed wire that once divided the city – and Europe. Berliners live among these reminders of evil.

But the 21st century has brought a new war to the streets of Berlin. The Russian embassy is a short distance from the site of Yevgeny Khaldei’s iconic image of the red flag raised over the ruined Reichstag. Now hoardings opposite the embassy bear the slogan “Brave Enough to be Ukraine”. A Ukrainian soldier’s face stares defiantly across the road.

Outside the embassy’s fortified entrance a small protest proudly flew Ukrainian flags. There are Ukrainian flags all over the city, and pro-Ukrainian graffiti is sprayed across a redundant section of the wall. It is a reminder of the fragility of peace.

I lived in Russia for many years as a journalist in the 1990s and again from 2006-2009. Perhaps I may one day be able to return there on friendly terms. It is hard to imagine when that might be, given that the Kremlin has taken to locking up journalists as spies.

The gilded letters in Treptower Park may shine whatever the weather, but, for the generations living today, Russia’s historical reputation is tarnished – however magnificent the mosaics praising Moscow’s military glory of the last century.

Back in London, I attended a service held at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral to remember victims of the war. Four hundred and sixty-one paper angels had been suspended above the heads of the congregation. Each represented a child killed in Ukraine in the previous 12 months.