One of the unexpected delights of the Cop27 climate conference was the Indian activist Licypriya Kangujam’s dogged questioning of Britain’s climate minister, Zac Goldsmith, about the UK’s jailed climate protesters. She chased him along corridors and through the doors that his entourage were trying to close in her face. Afterwards, she said, importantly: “We need to hold lawmakers accountable for their political decisions.”

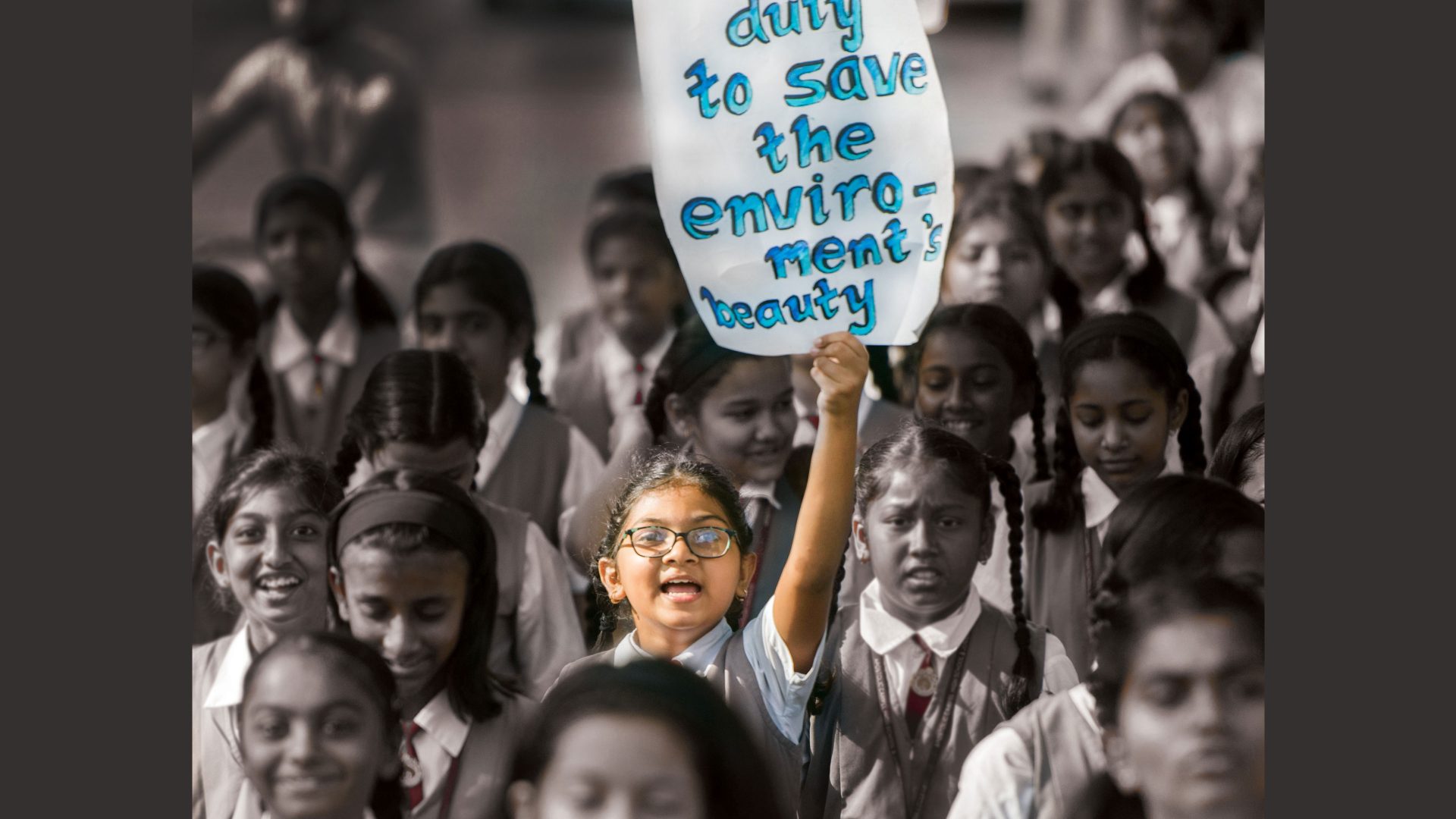

Kangujam is 11. She is part of the newest generation of climate activists who are putting adult politicians to shame with their straight talking and persistent demands, and they’re getting louder and angrier as the world’s temperatures reach catastrophic tipping points.

Amid the push for more action in the small window the world has left to avoid the worst, 2023 is set to be the year of youthful activists from the global south who, like Kangujam, are at the frontline of the climate emergency, in countries bearing the brunt of the changes they had almost no role in causing. Their dramatic, powerful stories of living through global warming-induced disasters, their savvy lobbying and increasing protest campaigns will make their mark after a year of yet more foot-dragging by national leaders determined to deprioritise armageddon.

Sweden’s climate action wunderkind, Greta Thunberg, who has long dominated the limelight, has vowed to “hand over the megaphone” to those in countries already suffering who have campaigned since their earliest days with a fraction of the publicity.

“I started almost as soon as I could speak. For us, it’s a matter of survival,” said Ayisha Siddiqa, a prominent climate activist from Pakistan, now 23. Long under siege from rising global temperatures, in 2022 a third of Pakistan’s land was engulfed by the worst floods in its history, following a severe heatwave. It cost more than 1,700 lives, affected another 33 million people, destroyed or damaged around 1.3 million homes and left 10 million children in immediate need of lifesaving support. “Worlds came to an end,” Siddiqa said. “My village doesn’t even exist any more. This kind of disaster will happen again and again.”

But the damage began much earlier. As a small child, Siddiqa – now in the US after her father won a visa lottery – saw her own community “condemned to multiple infrastructure projects, mining, dams,” all of which damaged the ecosystem and the livelihoods and health of those who lived there. The local river became dangerously polluted, affecting drinking water – she blames this for her grandparents’ deaths. “When the water they drank killed them, I knew I had to do something. I had to start speaking in public.”

There have been “tears in the room” at Siddiqa’s heartfelt speeches, but she emphasises that the world won’t change through a “public speaking tournament – panels, talks, yapping”. It needs money, action, and a refusal to bow to lobbyists, and the young campaigners need to work out how to play the negotiations, and get closer to forums where decisions are made.

Now, like Siddiqa – who campaigns for financial resources for the global south and fossil fuel non-proliferation – the new generation of campaigners such as Uganda’s Vanessa Nakate, Iranian-American Sophia Kianni and Kenya’s Eric Njuguna are knocking on the doors of political power. They were out in force at Cop27 in Egypt in November, some serving as part of the Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change, working with António Guterres. The United Nations secretary general is increasingly outspoken in his calls for leaders to act, saying that the world is “on the highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”, and that “we are in the fight of our lives – and we are losing”.

“People often applaud António for his speeches. I can tell you that the reason the secretary general is so radical and so morally competent and headstrong is his young advisory group,” Siddiqa told me.

Younger activists can be different because they won’t negotiate on vital issues, as they don’t have the leeway and time to compromise that the older generations did. They ask for the stars, and hold firm.

One non-negotiable for them has been the 2015 Paris Agreement target of keeping global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – a figure chosen because beyond that is the extinction point of nations such as the Maldives, the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu. The world is currently around 1.2 degrees warmer, and is on course to wildly overshoot, so debates have begun on whether to set a new, more realistic target. But the young activists argue that if the target shifts, the urgency will reduce and the ultimate warming levels will probably be higher still. So far, it remains.

Another issue on which youth campaigners – together with indigenous activists – have persisted is the “loss and damage fund”, which was finally created at Cop27 to provide financial assistance to nations most vulnerable and affected by climate change. And it’s from these nations that the most heart-rending stories emerge, bringing to life what has become an argument by numbers, of cynical trade-offs, of “but, what about the economy?”

When Kangujam’s escapades attract attention, she shifts focus to her own story, which reads like an odyssey through climate damage. Born in Manipur, a “small carbon-negative state of India, full of rich biodiversity and alluring atmosphere”, she went to school in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, where two large deadly cyclones hit in successive years. Delhi, supposedly safer, had dangerously high pollution levels and extreme heatwaves. India could soon become one of the first countries whose heatwaves exceed human survivability limits, according to a new World Bank study.

In 2019, aged six, Kangujam met world leaders, scientists, policymakers and other activists at the UN Disaster Conference in Mongolia, before founding the Child Movement – pushing for an Indian climate law, mandatory climate change education for all children, and for each of India’s 350 million students to plant 10 trees.

Aged nine, she told an interviewer: “As per historical data of the global carbon emissions, the global south is responsible for less than 10% of it but we’re the biggest victim of global climate crisis today… We deserve our voices to be heard by the world, and the world leaders to act on it.”

She’s very busy in 2023 – a schedule posted on her Twitter feed shows her attending “town hall” meetings in Delhi, Goa, Dubai and Berlin in the first three months of the year, with “school final exam” squeezed in between.

Kangujam and the other junior activists face adult lives of trying to survive and mitigate the effects of a crisis others did little to stop. They have had to grow up fast, getting to grips with complicated science, and learning how to brush off the usual backlash from those who object to being “lectured” by schoolchildren, especially when the earnest, pint-sized activists – far from being naive and unrealistic – are more informed.

As Revan Ahmed, a 12-year-old from Libya who was the youngest Unicef delegate at Cop27, said at the conference: “If you don’t listen to us now, when will you hear us? We are living the disasters now. We, the children, will not be victims. We want to change the situation.”

It’s an inspiring, but at the same time incredibly sad picture of young people working hard on both a local and international scale to push leaders of stature in the right direction, losing their innocence and childhood because of it, spurred on by the horrors they’ve seen.

Kianni, now 22, began her life in activism when at middle school. One night in Tehran the smog was so powerful she could not see the stars. Her Iranian relatives had no notion of the pollution caused by dirty energy, so she translated information for them. Later, she skipped school in the US to join Extinction Rebellion protests and held a hunger strike outside the offices of the then US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. In 2020, she became the UN’s youngest youth climate adviser. Shocked that the vast majority of scientific climate research – even the UN’s definitive IPCC reports – was in languages that many people could not understand, she founded the youth-led NGO Climate Cardinals, which features translations into more than 100 languages by 8,000 student volunteers.

“Just six years ago, two out of five adults had never heard of climate change,” Kianni explained in a TED talk. “(They) deserve to have access to the resources they need to make sense of these disasters destroying their communities. The more people are informed about the climate crisis, the greater chance we have to coordinate collective efforts in protection of the future of our planet.”

Some of those most affected by climate change now – and increasingly vocal about it – are indigenous communities around the world, numbering around 370 million people globally, from the Ecuadorian Amazon’s Sarayaku people to the Saami people living in northern Finland, Norway and Sweden, the Miskito community on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast to the Baka tribe living in the rainforests of Cameroon.

Martina Fjällberg, a 22-year-old reindeer herder and environmental activist from Sweden’s Saami community, is taking a degree in order to make scientists and politicians take her knowledge of nature more seriously. Swedish reindeer herders have long noticed the deterioration of nature – they now have little use for at least a quarter of their 200 words for snow as their lands warm – and work hard to sustain, defend and restore the biodiversity essential for their survival.

“Indigenous peoples’ tangible experience of nature’s decline gives them more insight than most into the threats facing our planet, so why are they still being forgotten in these debates?” she wrote in a joint article for Reuters with Princess Esmeralda of Belgium, an indigenous rights activist. “91% of (indigenous peoples’) lands (and those of local communities) are considered to be in good or fair ecological condition….”

Despite the immediacy of climate change for the global south, the spotlight is still mostly on the global north which, even considering the drought and wildfires in Europe over the summer, is less affected.

When I speak to Eric Njuguna, the 20-year-old activist from Kenya, he points out that more people in the capitals of the world’s richest countries have talked about campaigners throwing tomato soup on priceless artworks (protected by glass) than the thousands dying in Kenya and Somalia through ongoing droughts: “The fact that stories from the global south are not being amplified has led to a huge disconnect between the reality on the ground – what the true reality of the climate crisis means,” he said, “and those making decisions on issues such as mitigation finance playing down the urgency.”

I ask him what stories negotiators should be hearing now. “Stories of mothers who have lost children in their arms because they haven’t been able to feed them,” he said, without hesitation. “Stories of the ongoing drought in the Horn of Africa… which is affecting communities with the least role in causing the crisis. They’re bearing the brunt, losing families, losing the animals they depend on as a result of multiple failed rainy seasons.”

An activist since his early teens after severe droughts in Nairobi affected his school’s water supply, Njuguna organised the group Zero Hour and then Fridays for the Future Kenya, inspired by Thunberg’s school strikes. Last year he co-authored an essay with Thunberg and others for the New York Times, highlighting Unicef’s 2021 report that found 2.2 billion children were at “extremely high risk” of experiencing the consequences of climate change. He has met international politicians, including ministers. “But each time talking to them I feel there’s nothing new I can ever tell them – they have access to the best possible climate science, they have access to media sources, including the stories of journalists from here… But there’s the fact that they still want to continue the fossil fuel era when the science is clear that we need to stop oil and gas exploration.”

A record 600 fossil fuel industry lobbyists were allowed at Cop27, in effect negotiating on behalf of corporations with governments to water down declarations. According to the financial think tank Carbon Tracker, Shell, TotalEnergies, Chevron and other oil majors recently approved $166bn (£138bn) of investment in new oil and gas fields, more than a third destined for sites that will only be needed if fossil fuel demand reaches levels that push warming above 2.5C.

Young activists I spoke to see 21st-century capitalism as a huge barrier to successful climate action, in the face of energy companies trying to extract just another couple of decades of profit before they must throw in the towel. Even new measures such as carbon credit-trading enable big polluters to buy the right to pollute from poorer nations, they complain, which are then left with little room to manoeuvre with their own emissions. As for the loss and damage fund, this is an “empty bucket”, they say, and even if eventually filled, the donors will preen about helping the poor – yet should understand they’re really paying “reparations, not aid”.

To push their point, however, they need to be at the table with power and a vote, as fully-fledged youth negotiators who will have to deal with the consequences of any failure.

“Of the world’s population, 60% is below the age of 35. Young people are the greatest stakeholders,” says Siddiqa… “Things will only change if we are helping write policies. I don’t think this is impossible or romantic, or a pipe dream. It just needs political will.