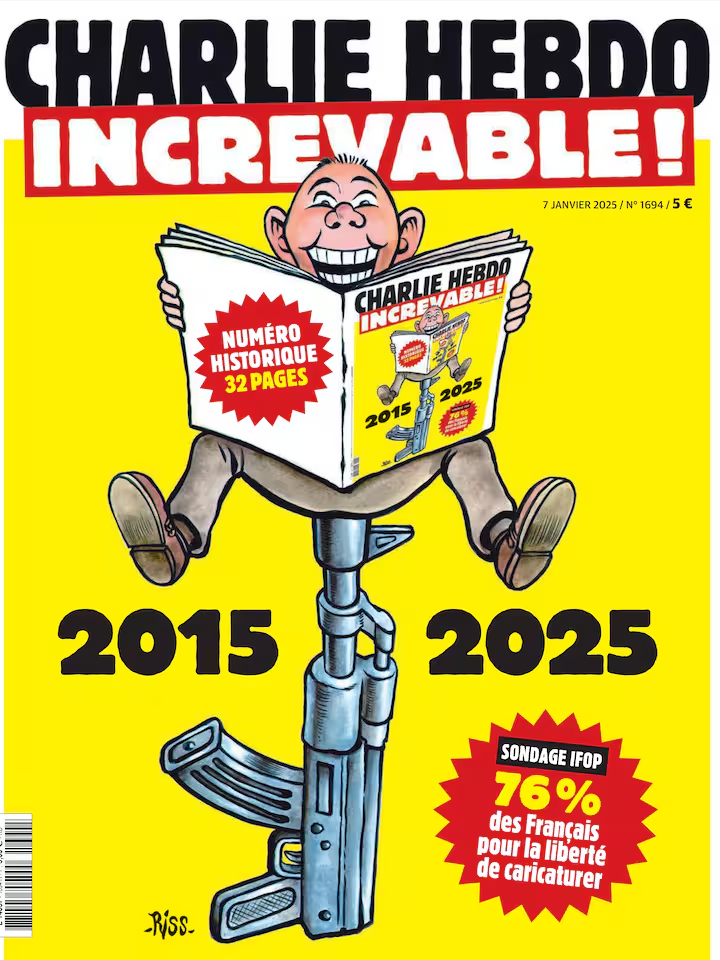

“Indestructible!” The headline on Charlie Hebdo’s special anniversary edition sends a clear message to the world, ten years after Islamist terrorists slaughtered 12 people at the satirical weekly, ostensibly as vengeance for “insulting” the Muslim Prophet Mohammed in a drawing.

The cheekily defiant band of cartoonists and writers, who put together the French satirical newspaper, operate in secret and under constant threats from fatwas and jihadists. Charlie will keep caricaturing figures of any religion, as underscored by its competition to draw the “meanest” depictions possible of God.

“If we want to laugh, it’s because we want to live… undestroyable and universal,” declares Riss the editor, who survived the attack. The cover features a laughing reader under the word “INCREVABLE!” celebrating the publication’s survival.

Also on the front page are the results of a new IFOP poll commissioned by Charlie Hebdo, showing that 76% of French people support the freedom to caricature. Inside, there is a reproduction of one of Cabu’s best-known and most controversial caricatures from 2005, depicting the Prophet Mohammed beneath the words, “Mohammed overwhelmed by fundamentalists,” covering his eyes and saying, “It’s hard to be loved by idiots.”

But a decade on, are we still Charlie? Is free speech invincible in France and across the world, which spontaneously rallied around the newspaper after the attack?

On that day, two jihadists, the Kouachi brothers, burst into Charlie Hebdo’s editorial meeting and within minutes had slain beloved cartoonists Cabu (Jean Cabut), Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier), Honoré (Philippe Honoré), Tignous (Bernard Verlhac), and Wolinski (Georges Wolinski); economist Bernard Maris; columnist Elsa Cayat; and proofreader Mustapha Ourrad. Maintenance worker Frédéric Boisseau, police officer Franck Brinsolaro (assigned to protect Charb), guest Michel Renaud, and police officer Ahmed Merabet — shot as the gunmen fled — were also killed.

The next day on January 8 a third jihadist and associate of the Kouachis, Amedy Coulibaly, murdered police officer Clarissa Jean-Philippe in a connected attack in the Paris suburb of Montrouge. On January 9 the same jihadist killed four Jewish men in an antisemitic terror spree — Yohan Cohen, Yoav Hattab, Philippe Braham, and François-Michel Saada — during a hostage standoff at the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket in Paris.

These attacks sent shockwaves through France and the world, igniting an unprecedented wave of global solidarity, and a surge of Al Qaeda- and Islamic State-inspired attacks in France (The Bataclan, Nice), Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In the days after the massacre, an estimated four million people marched in Paris and across France, the largest street demonstrations since the liberation of 1944. The slogan “Je Suis Charlie” became a global rallying cry for freedom of expression. Who could forget the image of more than 50 world leaders, including chancellor Angela Merkel, prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas, and Malian president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, walking arm-in-arm with president François Hollande in a powerful display of unity?

The weekly publication, which had been targeted by extremists since republishing the Danish Mohammed caricatures in 2006, became a symbol of defiance against fundamentalism and terror.

Charlie had existed since 1970 and was anchored in French traditions of caricature, mockery of religious clerics, muscular free speech convictions grounded in the works of thinkers like Voltaire, and attachment to secularism – but the consensus around the attack soon fell apart.

Emmanuel Todd argued in a 2015 book that the spirit of Charlie was “hysterical”, atheistic, and “Islamophobic”, and that the demonstrations did not attract many French citizens of North African and Muslim backgrounds. Accusations of Islamophobia leveled at Charb, Cabu, and Charlie resurfaced, with critics overlooking the newspaper’s equal-opportunity satire of all religions and ideologies.

Only a few months after the terrorist murders at the satirical publication, a group of acclaimed writers including Michael Oondatje, Peter Carey, and Joyce Carol Oates signed a letter of protest boycotting the Freedom of Expression Courage Award given to Charlie Hebdo by the PEN literary association in New York. They cited “cultural intolerance”, and in Carey’s case the “cultural arrogance of the French nation”.

In 2020, violent demonstrations erupted in Muslim-majority countries, spurred by President Erdogan of Turkey, when president Emmanuel Macron defended free expression and the right to caricature, following the murder of the French teacher Samuel Paty. Paty was beheaded by a Chechen-born terrorist after local Islamists whipped up an online frenzy of fatwas denouncing Paty for showing Charlie Hebdo cartoons in a class on freedom of expression.

Three years later, in October 2023, Dominique Bernard, another educator, was fatally stabbed outside his school in northern France for being a French teacher – a subject his Islamist attacker associated with promoting democratic and secular values. Even on the mainstream Socialist left in France, there are figures willing to label Charlie’s supporters, like the Arab-background comic Sophia Aram, as racist and Islamophobic.

Threats to free speech predated the attack on Charlie – and they persist still. In 2022, Salman Rushdie narrowly survived an attack by a Hezbollah- and Iran-linked jihadist, losing an eye and partial use of a hand, decades after the 1989 fatwa issued against him for his depiction of the Muslim prophet in The Satanic Verses.

Meanwhile, in the UK in late 2024, the MP Tahir Ali called for blasphemy laws to punish the “desecration” of religious texts, including the Quran – a call astonishingly endorsed by Keir Starmer, who urged condemnation of such “desecration”.

Notably, very few French newspapers are prepared during this week of commemorations, to take the grave risks that come with reprinting any of Charlie’s caricatures of Mohammed. The newspaper itself has not gone that route either with a front cover that could inflame passions globally or in France.

Despite these challenges, Charlie Hebdo endures. Corinne Rey (Coco), one of the newspaper’s surviving cartoonists, still draws for Charlie and is also the in-house cartoonist for Libération.

After Charlie’s offices were firebombed in 2011 following a front-page cartoon by Luz depicting Mohammed laughing, Coco was already preoccupied by the lack of support for the newspaper. “We often heard things like, ‘Yes, but…’ or ‘Didn’t you bring this on yourselves…?’ It was pathetic.”

“We are still fighting, even today, against these kinds of reactions. In a newspaper, satire may seem harsh, even violent, but it’s still just ideas and drawings – it doesn’t kill. People may not like it. But nothing can justify drawings being a problem to the extent of receiving threats or being killed.”

For Anne Rosencher, editor of l’Express magazine, the anniversary of January 2015 is not only sorrowful because it commemorates attacks that wounded France. “It is also heartbreaking because, ten years later, one cannot help but draw an embittered and worrying conclusion. Fear of Islamism has grown, and silence has taken hold.”

Charlie Hebdo may not have been silenced, yet its resilience comes at great personal and professional cost. Last year, Charlie’s webmaster, Simon Fieschi, who was gravely wounded in the 2015 attack, died at the age of 40, described as the latest victim of the terrorist attacks. Coco, who was forced at gunpoint to let the Kouachi brothers into the building, lives under permanent police protection, haunted but undeterred.

“January 7 still inhabits me constantly,” she says. “What’s also hard to accept, ten years later, is the sense of powerlessness. Those guys were cowards for attacking cartoonists and a woman like me, 5’3” tall and weighing 110 pounds. There was a disproportion in everything. Their hatred, our pacifism. Their weapons, their monstrosity, and us, there with our quills, our pens, our pencils, defending ideas, laughing.

“By wanting to kill Charlie, they thought they could impose their fanatical laws, while we advocated freedom – freedom to think and to draw. A true clash of civilizations.”