During the long last months of the late unlamented pro-Brexit Conservative government, we heard a lot about chaos, not least the astonishing disorder brought about by the short-lived prime minister Elizabeth Truss and the even shorter-lived chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng. The opposition parties did not tire of asserting how much they were looking forward to bringing order to the chaos that the nation had been forced to cope with for the past several years under the previous regime.

The word chaos first made an appearance in written English in the late 1300s, when it generally meant “a gaping void; an immeasurable empty space” – which some would no doubt argue was an entirely appropriate description of our previous government’s front bench.

This word came into English either via Old French or directly from Latin, where it was originally a straight borrowing from Greek. In Ancient Greek khaos meant “abyss, a vast wide empty open gaping space”; it had come from an Indo-European root ghieh – “to yawn, gape, to be wide open”.

The most usual current English meaning of chaos today is “orderless confusion”, but this meaning did not emerge until around 1600. Modern Greek kháos has roughly the same meaning as in contemporary English, but Greek speakers’ pronunciation of the word can sound to English ears rather as if they are saying “house”.

The word chaos is etymologically related to chasm and to gape. It also has the same ancient origin as yawn, as well as gap, gasp, gawp and hiatus. And, interestingly, it also spawned the term gas.

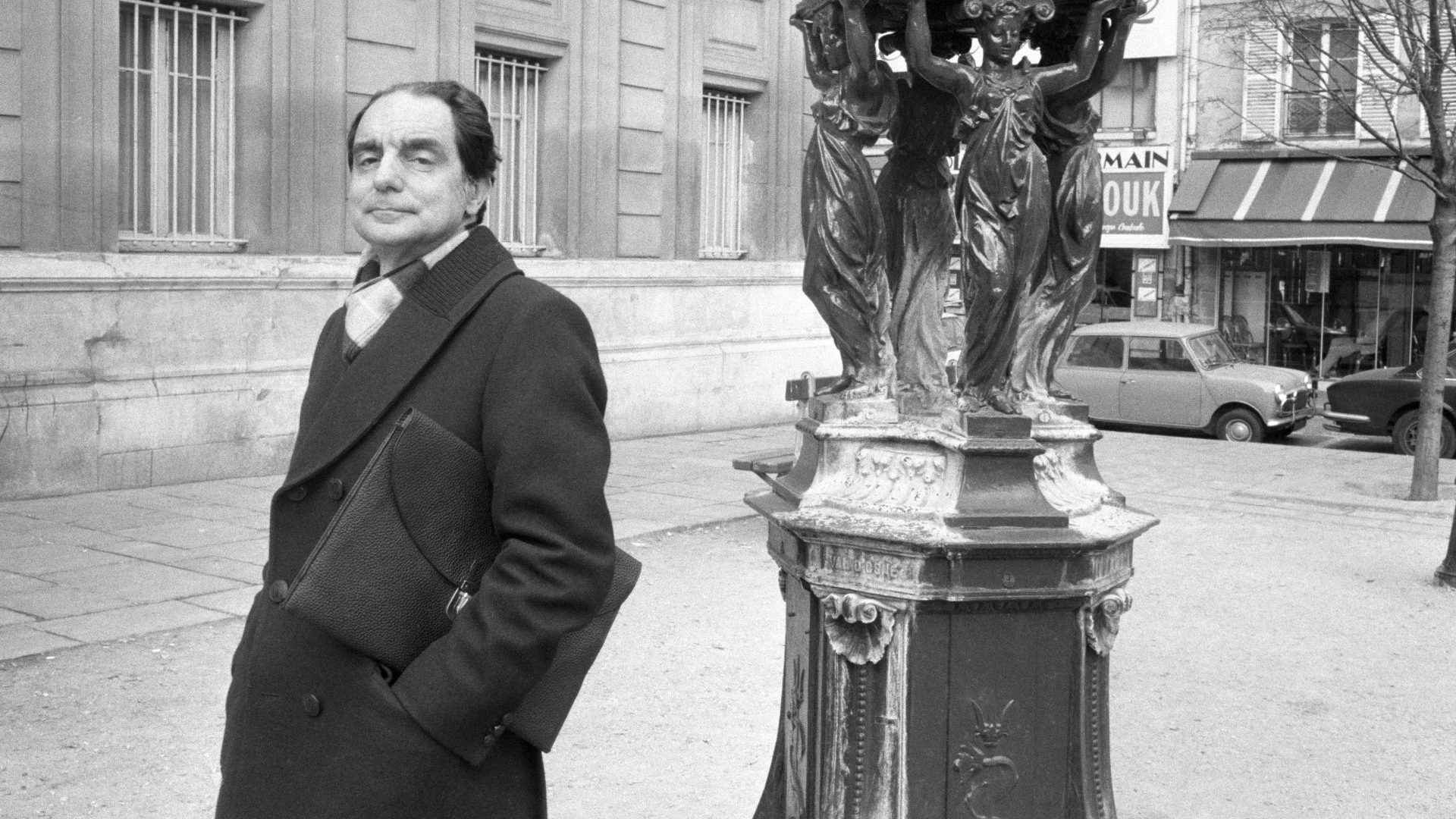

The word gas is only about 500 years old. It was coined by the Flemish physician and natural philosopher Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580-1644), who stated that “I have called this vapour [it was carbon dioxide] gas, not far removed from the Chaos of the ancients”. It is important to understand that in Dutch/Flemish the letter g is pronounced more or less the same as the Greek letter χ, which is often transliterated into written English as ch (as in Scots loch) or kh – as in khaos.

Van Helmont was born in Brussels, which is now a predominantly though by no means entirely French-speaking metropolis, but at the time of his birth it was a very much a Dutch-speaking city. French did not become predominant in Brussels until the late 1800s.

Van Helmont’s lexical innovation was an enormously successful one, and it very rapidly became extremely widespread around the world. French gaz appeared in 1670, Italian gas in 1683, Swedish gas in 1711, and German Gas in 1796. Variants of gas such as Basque gasa and Finnish kaasua are now found in very large numbers of languages, but there are some exceptions, even in European languages. In some countries, puristic nationalist decisions taken by influential scholars who wanted to avoid the international form gas in favour of terms coined out of local indigenous material have won out.

The Welsh word for gas is nwy, which was a neologism invented by the Welsh lexicographer William Owen Pughe (1759-1835). The Czech word plyn was introduced by the scientist Jan Svatopluk Presl, who was born in Prague in 1791 and who borrowed the word from the closely related West Slavic language, Polish, where płyn means “liquid”.

A gas, of course, is not a liquid, but neither is it total chaos. That was our previous government.