Papiamentu, also known as Papiamento, is a European language with about 500,000 speakers. If you have never heard of it, this is probably because, while it is a language of Europe, it is not generally a language in Europe.

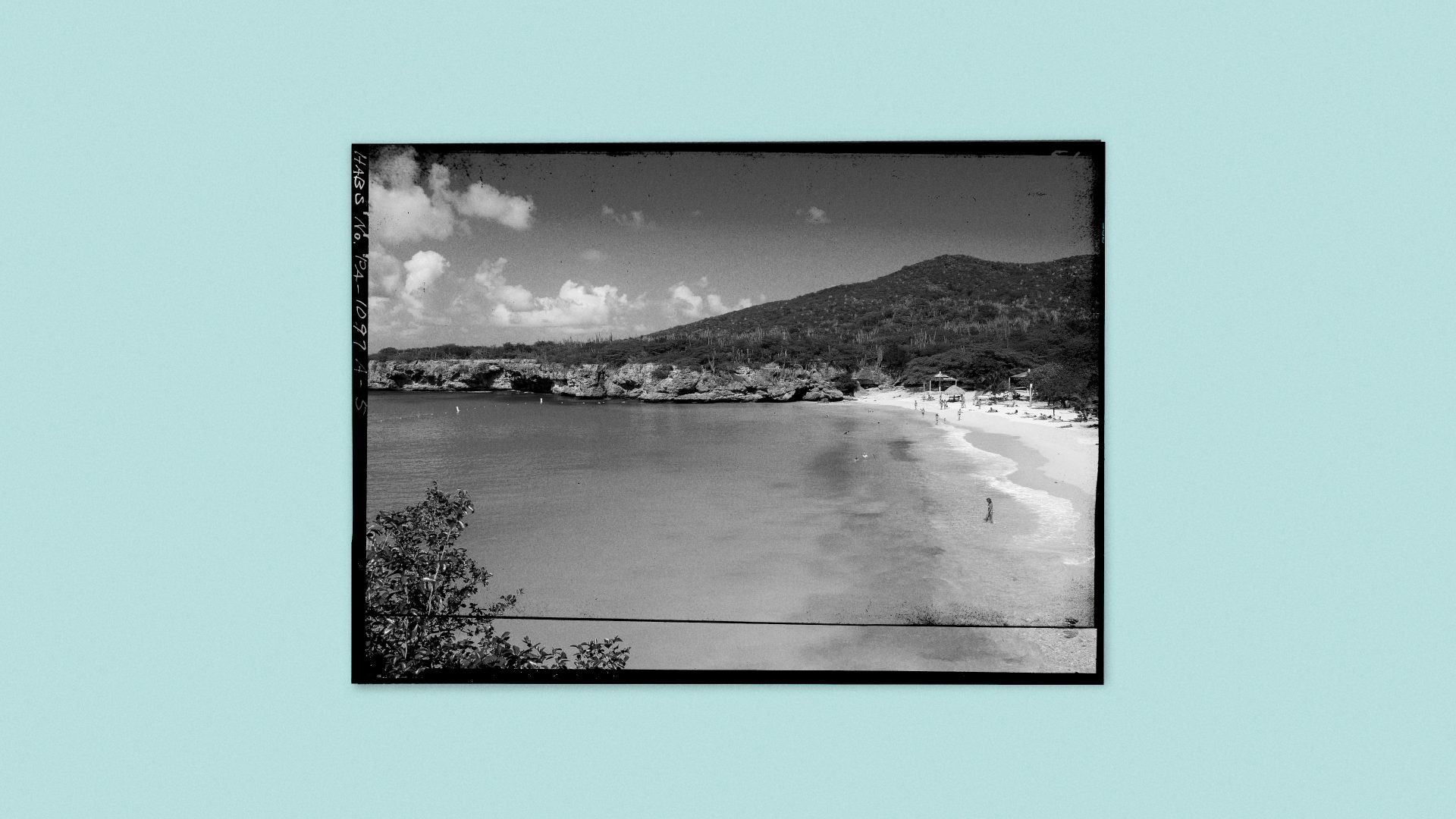

It is the language of the so-called ABC Islands – the Caribbean former Dutch colonial polities of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, which lie to the north-east of the South American continent off the coast of Venezuela, about 13 nautical miles from the mainland at the nearest point. Papiamentu has official status on these islands, where it is spoken by everybody.

The islands were originally inhabited by indigenous peoples who spoke Arawakan languages, which were also found elsewhere in the Caribbean and on the South American mainland. The islands were colonised by Spain in 1527, but were seized from the Spanish by the Dutch in 1634, and became one of the centres of the Dutch slave trade.

Papiamentu is a young language in the sense that it has been in existence only since the 1600s or 1700s. It has a complex history of contact and mixture. It is a creole language, having been formed in the colonial period as a result of the rapid and intense contact between many different African and European languages which occurred during the Atlantic slave trade. The language most likely developed originally on the west African coast, perhaps especially on the Portuguese Cape Verde islands, where today another Portuguese-based creole language, called Kriol, is spoken.

Noun and verb forms in Papiamentu typically derive from Spanish, like muhé “woman” from mujer, homber “man” from hombre, and hasi “to make, do”, from hacer. Grammatical words tend to come from Portuguese: na “in” from na “in the”; te “until” from até “until”; nos “we”. The name Papiamentu itself derives from the Portuguese verb papear “to chat”.

The historical relationship of the language to Spanish and Portuguese can also be illustrated from the different numeral systems. The numerals from 1 to 5, Spanish uno dos tres cuatro cinco and Portuguese um dois três quatro cinco, correspond to Papiamentu unu dos tres kwater sinku. The numbers from 6 to 10 are also similar – Spanish seis siete ocho nueve diez and Portuguese seis sete oito nove dez are in Papiamentu seis shete ocho nuebe dies.

But notice what happens when the numbers go beyond 10. Portuguese onze doze treze “eleven twelve thirteen” have in Papiamentu become diesun diesdos and diestres, literally “ten-one”, “ten-two” and “ten-three”.

This is typical of the sort of changes that happen where sudden and large-scale contact occurs between adults speaking different languages. In the case of the formation of Papiamentu, contact most probably involved west African languages, native American languages, and the two major Iberian tongues, including also a significant proportion of speakers of Judaeo-Portuguese, plus English and Dutch.

Adults, who are typically much worse language learners than small children, lessen the cognitive load of foreign-language learning for themselves by adopting less irregular and more transparent language forms: if you already know that dies means “ten” and dos “two”, then diesdos is totally transparent, unlike doze.

Creole languages are perfectly normal languages, and no less adequate than any other human language, but they generally display fewer irregularities than other languages.

TWELVE

The English word twelve is not much more transparent than its Portuguese equivalent doze. It comes from Old Germanic twalifi-, where twa– was “two” and lifi– had some (not very certain) connection to “leave”, so the original meaning was probably something like “two left over after counting to ten”.