As Keir Starmer heads into the holiday season with a spruced-up shadow cabinet, seemingly to forge a centrist path to a brighter electoral future, he might want to set aside some time to dip into The British General Election of 2019 for some sage lessons from the last ballot.

The devil is in the data and this 700-page tome reveals long-term voting trends related to class, age and education that will offer much food for thought for Starmer.

The election two years ago boiled down to two questions: should Brexit go ahead and who should be PM – Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbyn?

On Brexit, 52% voted for a party that backed a “people’s vote”, or second referendum, while 47% voted for a party to “get Brexit done”. Ahead of the election, YouGov came to the same conclusion via a different route: by 47% to 41%, they found that the public thought we were wrong to vote to leave the European Union. When the UK finally left after the vote, only a minority of Britons were satisfied.

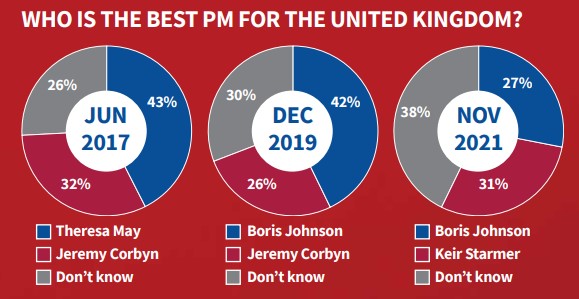

On the leadership question, the margin was 15 points, (41% Johnson; 26% for Corbyn). True, on average, one voter in every three didn’t care much for either of them, but the balance among those who did take sides proved decisive.

The most telling passages in The British General Election of 2019 contain quotes from focus groups in Red Wall seats. “I like the Labour Party, I just don’t like Corbyn,” and, “You need somebody who’s got direction, and he hasn’t got any.”

This helps to explain the Tories’ 80-seat majority. Thousands of progressive, internationally minded voters in key marginal seats disliked Johnson but dreaded the alternative. Tactical voting, which cost the Tories around 30 seats in 1997, was almost non-existent. They benefitted from pro-European voters who feared Corbyn more than Brexit.

In 1967, political scientist Peter Pulzer wrote: “Class is the basis of British party politics; all else is embellishment and detail.” He was right. In the 1970 election, Labour’s vote divided as follows: C2DE (working-class) 10 million, ABC1 (middle-class) 2.2 million. Two years ago, the figures were: C2DE 4.1m, ABC1 6.2m. Six million fewer working-class votes; four million more middle-class votes.

This switch is partly explained by changes in Britain’s overall electorate: a two-to-one majority of working-class voters half a century ago, compared with a four-to-three majority of middle-class voters today. When we combine the two trends – the changes in overall class numbers, and the changes in the way people vote – we can see how British elections have been transformed.

Labour has been attracting a smaller proportion of the shrinking working-class electorate, and a rising proportion of the expanding middle-class electorate. Which should be good news except for the fact that compared with half a century ago, the collapse in Labour’s working-class support has been greater than its gains among middle-class voters. Overall, we have reached the point where today’s ABC1 and C2DE voters think alike about politics. Like Monty Python’s Blue Norwegian, Pulzer’s observation has expired. It is an ex-theory.

Instead, the big divide is age. This can be seen by comparing the results of two nationally similar elections. Margaret Thatcher defeated Labour in 1987 by 12%, the same margin as Johnson’s Tories in 2019. But the generation gap was very different. In 1987, the Tories enjoyed a 2% lead among voters under 35, and a 15% lead among those over 55 – a generation gap of 13 points. The equivalent figures in 2019 were: under 35s, Labour lead 27%; over 55s: Tory lead 39%. Not so much a generation gap as a yawning gulf.

An educational divide has also emerged, with graduates tilting more towards Labour, compared with non-graduates.

These are more than statistical oddities. They go to the heart of what happened two years ago, not least in the Red Wall towns that used to give Labour big majorities. A narrative has developed saying these areas are electorally distinct and that Labour cannot return to office without winning them back by adjusting policies, especially on Brexit. This is not necessarily true.

Red Wall seats have not become abnormal, but the opposite. Until the 1990s, Labour enjoyed a large Red Wall bonus. In 1997, they won 43% across England, but 64% in an average of 10 Red Wall seats that now have Tory MPs. That 21-point bonus had halved to 11 points by 2016, before the referendum. It is now three points. Brexit accelerated the slide but did not cause it.

Instead, what we are seeing is a demographic shift. These areas used to boast big industries, overwhelmingly employing unionised manual workers – Labour’s core vote. The industries have long gone and historic loyalties have gone with them. Today’s Red Wall towns are similar to the English average, with slightly below-average numbers of strongly pro-Labour voters and slightly above-average numbers of older voters, now overwhelmingly Tory.

The demographic balance has shifted from strongly pro-Labour to marginally pro-Conservative.

In short, Labour doesn’t have a “Red Wall problem” per se. It has “everywhere” problems. If Labour can regain ground nationally among the demographic groups that have deserted it, recovery in the Red Wall towns will follow. If it can’t, a fifth election defeat seems inevitable.

Labour faces a specific challenge when it comes to Brexit. If the debate is framed as a nativist/ cultural battle, the party’s liberal values are bound to suffer. Starmer needs to turn Brexit into an argument about jobs and prosperity. Given the damage it’s doing to industrial areas, this is a battle he should be able to win.

That’s not to say it will be easy. To win a majority, Starmer will have to do better than Tony Blair did in 1997. Then, a 10% swing gave Labour a landslide majority. At the next election, the same swing would leave the party 20 seats short (even more if the election is fought on new boundaries). To win outright, Labour needs a 12% swing.

A minority Labour government is more realistic, which would mean support from the Scottish National Party and Liberal Democrats.

Is a minority government even feasible? The answer is yes, and that’s because of Johnson’s own ratings. He ended the 2019 campaign with 41% saying he would make the best PM. But on the eve of the 2017 campaign, the equivalent YouGov survey found that Theresa May was preferred by 43%, even after she had fumbled badly and lost ground.

In fact, Johnson has never been as popular with voters as his supporters think. Today, he is the preferred PM of 27%, (Starmer’s 31%;“don’t knows” 38%). When Ipsos MORI asks its long-term tracker question: how people regard the way the prime minister is running the country, Johnson’s net rating is -27 (satisfied 24%, dissatisfied 51%). He might recover: Thatcher had worse mid-term ratings before her 1983 and 1987 victories. But the notion that he has some personal magic that makes him invincible is simply wrong. Labour’s task is tough but not impossible.

The British General Election of 2019, by Robert Ford, Tim Bale, Will Jennings and Paula Surridge, is published by Palgrave Macmillan, £24.99.

Polling expert Peter Kellner is a former president of YouGov and a BBC election night analyst.