Rare is the literary genre revolutionised by a single book. It’s difficult to think of many instances when a title is not only groundbreaking in form and content but also sells in huge quantities, changing the entire literary landscape it inhabits.

Don Quixote is often credited as being the first novel, but Cervantes was establishing a genre, not transforming one. Ulysses had a huge influence on modern fiction without ever being a bestseller. The Harry Potter series revitalised literature for children and young adults, but its rip-roaring, old-fashioned storytelling was never revolutionary in either concept or execution.

Perhaps the only book to have genuinely reinvented an entire genre is Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch. With well over a million copies sold, it has been adapted for stage and screen and in 2012 was elevated to the prestigious

Penguin Modern Classics imprint. When it was published 30 years ago, it became the first football title to win the William Hill Sports Book of the Year. Most importantly it galvanised football literature, its influence extending from autobiography to history to the game’s farthest backwaters in ways still recognisable today.

Hornby’s memoir was a rational analysis of an irrational obsession. He told of how his love for Arsenal permeated every aspect of his life and had done so ever since his first visit to Highbury with his father. Slightly baffled that he continued to function as a rational adult when so many of his waking hours were spent thinking about football, Hornby even confessed to hoping his spirit would be able to linger posthumously at Highbury (although the ground’s subsequent development into luxury flats would have left the spectral Hornby watching nothing more exciting than a web designer playing Fortnite while his sourdough proved).

But its anniversary coincides with a World Cup that represents all that’s

wrong with modern football. Over 6,500 migrant workers died building the stadiums in Qatar, to stage a tournament that has been protested against even by the players competing in it. But the 150th anniversary of the first football international between England and Scotland is a reminder of the deeper cultural importance of football.

These competing ideas of football and of what makes the sport relevant and valuable, both socially and personally, make it the perfect time to examine the impact and legacy of Hornby’s masterpiece.

The received wisdom is that football at the dawn of the 1990s was a dispiriting spectacle watched in crumbling stadiums by a few thousand grunting troglodytes more interested in stabbing each other than following the game. Football was Britain’s embarrassing relative, a nation’s shame.

Then Gazza burst into tears in Turin, kindly telly-uncle Rupert Murdoch showered the game with banknotes, the Premier League was launched in a cannonade of confetti and, hey presto, not only was football out of the wilderness, suddenly it was the biggest show in town.

That received wisdom is, well, a little misleading. Football had its issues like most aspects of society, but its pariah status had been stoked in order to draw attention away from wider government failings. When disorder broke out at the football, there were usually cameras there to record it. When disorder broke out on high streets when the pubs shut on a Friday night, there were no cameras. This turned a social issue into a specifically football one. During the 1980s Graham Kelly, secretary of the Football Association, answered Margaret Thatcher’s hectoring about when he was going to do something about football hooliganism by asking: “When are you going to keep your hooligans out of my football grounds?”

Despite a steady decline in attendances, football remained one of the most popular entertainment pastimes in the country. Matches were shown live on terrestrial television, significant chunks of newspapers were filled with football news, the weekly adventures of Roy of the Rovers held kids spellbound and Match of the Day had been a BBC Saturday night staple since 1964. The FA Cup final remained one of the biggest television events of the year, with both teams miming awkwardly through terrible celebratory ditties

on that week’s Top of the Pops. A national scourge? Hardly.

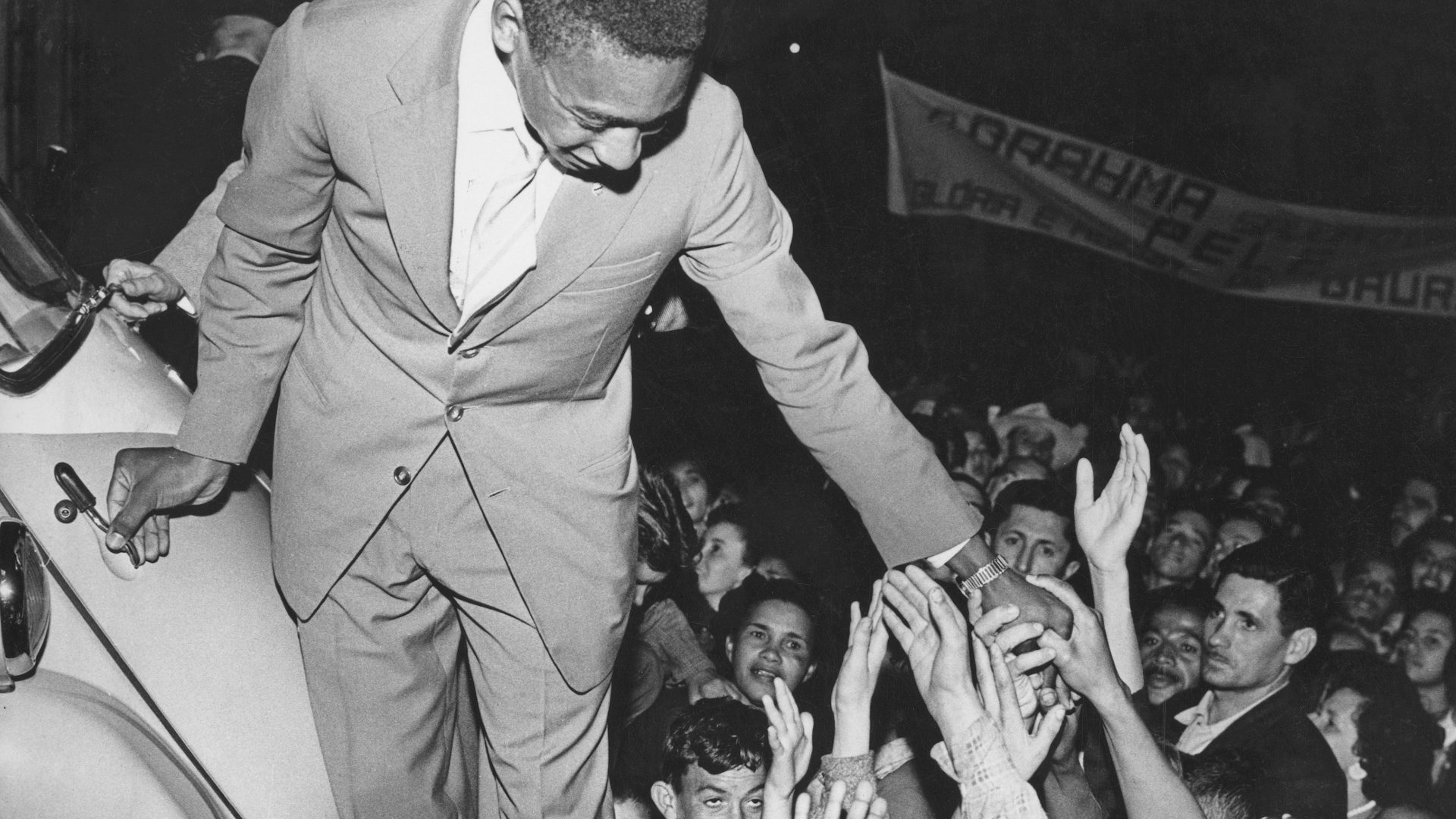

The game had reached a significant turning point in 1992. The 1990 World

Cup and England’s unexpected progress to the semi-finals prompted a resurgence in wider interest despite shrinking crowds, the demonising of

fans and a series of entirely preventable tragedies in chronically neglected stadiums, from Ibrox in 1971 to Hillsborough in 1989.

The 1990 Taylor Report into the latter disaster saw football grounds made fit for purpose again, while 1992 was year zero of the lucrative breakaway English Premier League. Also that year Channel 4 began live coverage of matches from Italy’s Serie A on Sunday afternoons and broadcast proceedings as England was selected to host the 1996 European Championships. It was also the year that Fever Pitch was published.

With a few notable exceptions, football had never produced much in the way of significant literature, its library consisting mainly of dry club histories and tedious autobiographies whose only whiff of literary merit came occasionally in their titles: Ure’s Truly by Ian Ure; Tall, Dark and Hansen by Alan Hansen and Alan Ball’s It’s All About A Ball (geddit?)

Among rare exceptions were: Hunter Davies’s The Glory Game – a chronicle of Tottenham’s 1971-72 season; Only a Game? by Eamon Dunphy, a warts-and-all 1970s diary of a season by the former Millwall midfielder; and Arthur Hopcraft’s 1968 sociological masterpiece The Football Man. These were rare

ventures beyond the anodyne that remain classics – but that was about it.

With fans increasingly fed up with being blamed for the ills of society, the late 1980s saw an explosion in football fanzines that gave them a voice for the first time. Now there were forums to campaign for the removal of the game’s ineffective administrators, to criticise their clubs’ dubious owners as well as to debate the worst haircuts ever to step on to the pitch.

Loudly and eloquently, fanzines countered the prevailing narrative to show that football supporters were as smart, witty, community- minded and as capable of creative, intelligent campaigning as anyone else. And some of them could write like a dream.

A few months after the 1990 World Cup, Pete Davies’s book All Played Out

appeared, to wide acclaim. It was a fan’s-eye view of the tournament, boasting access to the England squad that today’s football writers can only

dream about. Davies, it seems, simply walked into the team hotel and chatted to the players – unthinkable today. But it was Fever Pitch that truly

revitalised football writing and transformed the wider perception of

the football supporter.

The secret of the book’s success was in how Nick Hornby wrote about matches and players not in the traditional method of who scored and when, but by lacing those matches and players into the context of his own life. Like most brilliant ideas it was, in hindsight, obvious. Fever Pitch is a chronicle of how most of us experience football: the people we go with, the journeys to and from the ground, the routine of turnstile, programme seller, pie stall, reaching the place we always stand or sit. Football and the stadium where we

watch it is, for all our house moves, relationship break-ups, career changes and bereavements, always there as a reassuring constant presence in our lives from childhood upwards, something Hornby was the first to articulate in print.

Reading Fever Pitch felt like a release. There was an overwhelming relief among readers that we weren’t alone, that this book echoed everything we felt and believed. Hornby confirmed that it was OK to be a football fan, that our irrational quirks and obsessions when it came to our teams differed only in the colours of our scarves. We now had something we could point to, to say look, just read this and you’ll understand.

The book’s wider impact was twin- pronged. First it showed publishers that there was a huge audience clamouring for good-quality football writing. Second, it inspired a new generation of writers emerging from outside the matchday press box who had interesting, intelligent and witty things to say. Some brilliant books appeared, like Simon Kuper’s global exploration of football and conflict Football Against the Enemy and Harry Pearson’s “mazy dribble” through football in the north-east of England The Far Corner.

Coverage of the game in Europe had been almost non-existent until Fever Pitch paved the way for deep and specialised explorations like David Winner’s Brilliant Orange, an absorbing analysis of what football means to the Dutch, and Passovotchka by David Downing, the story of Moscow Dynamo’s remarkable British tour of 1945. Andy Dougan’s Dynamo told the extraordinary story of Dynamo Kyiv’s players’ valiant attempt to keep the Ukrainian flame alive through football during Nazi occupation.

Absorbing narrative histories of football in Germany, Spain and Italy appeared, as did, ahem, my own Stamping Grounds, following tiny

Liechtenstein’s attempt to qualify for the 2002 World Cup despite fielding a

team of bank workers, schoolteachers and postmen.

None of these books would have happened without Fever Pitch. We could forgive Hornby for presenting his support of one of England’s most successful clubs as a catalogue of agony and disappointment – try following Charlton Athletic, mate – because we identified with him and what he felt. Best of all, we could rejoice in it at last.

“Please be tolerant of those who describe a sporting moment as their best ever,” he wrote. “We do not lack imagination, nor do we have sad and barren lives; it is just that real life is paler, duller and contains less potential for unexpected delirium.”

Thirty years on those words ring as true as on the day they were written.