Despite moving house a month ago, I am still undertaking the slow process of working through the teetering piles of book-filled boxes that dominate every room.

As with all the moves I’ve ever made, good intentions about organising the books logically before the distant rumble of approaching vans can be heard came to naught. I am faced with brown walls of boxes everywhere I turn, each with the word “books” scrawled on them.

The unpacking process has not exactly been assisted by my picking up and reading books I’ve not seen for ages even though they have been in plain sight on my shelves all along. Chin in hand, rear end on a box, I am passing more time than I should in literary contemplation while tutting quietly at the distracting sound from downstairs of my wife trying to shunt large, heavy items of furniture around on her own.

Last week saw a particularly lengthy period of non-productivity thanks to an old blue hardback with faded gold lettering on the spine that I had not thought about in far too long. I can’t even remember how I came to acquire The Best of Modern European Literature but there it was, looking up at me from a box, goading me into flicking through the pages and losing myself among the wide and varied geography of our literature.

This is no randomly compiled anthology, however. The Best of Modern European Literature, or Heart of Europe to use its proper name as displayed on the title page, was a product of circumstances global and personal. Compiled by the German writer Klaus Mann, son of Thomas, and his compatriot and fellow writer Hermann Kesten, Heart of Europe was put together in exile in the USA and published in 1943.

Containing stories, essays, poems and novel extracts by 140 writers from 21 European countries, Heart of Europe limits itself to the two decades between the end of the first world war and the start of the second. It is a passionate, assertive celebration of Europe at a time when the continent was most under threat, a collection designed to remind the world of what is good about Europe and to remind Europeans of what they were fighting for.

“Europe’s social and political elites failed signally in their task of leading and enlightening the muddled, malcontent peoples,” Mann writes in his preface. “But the record of the literary men [sic] is, on the whole, most impressive and more honourable than is that of the politicians and industrialists.”

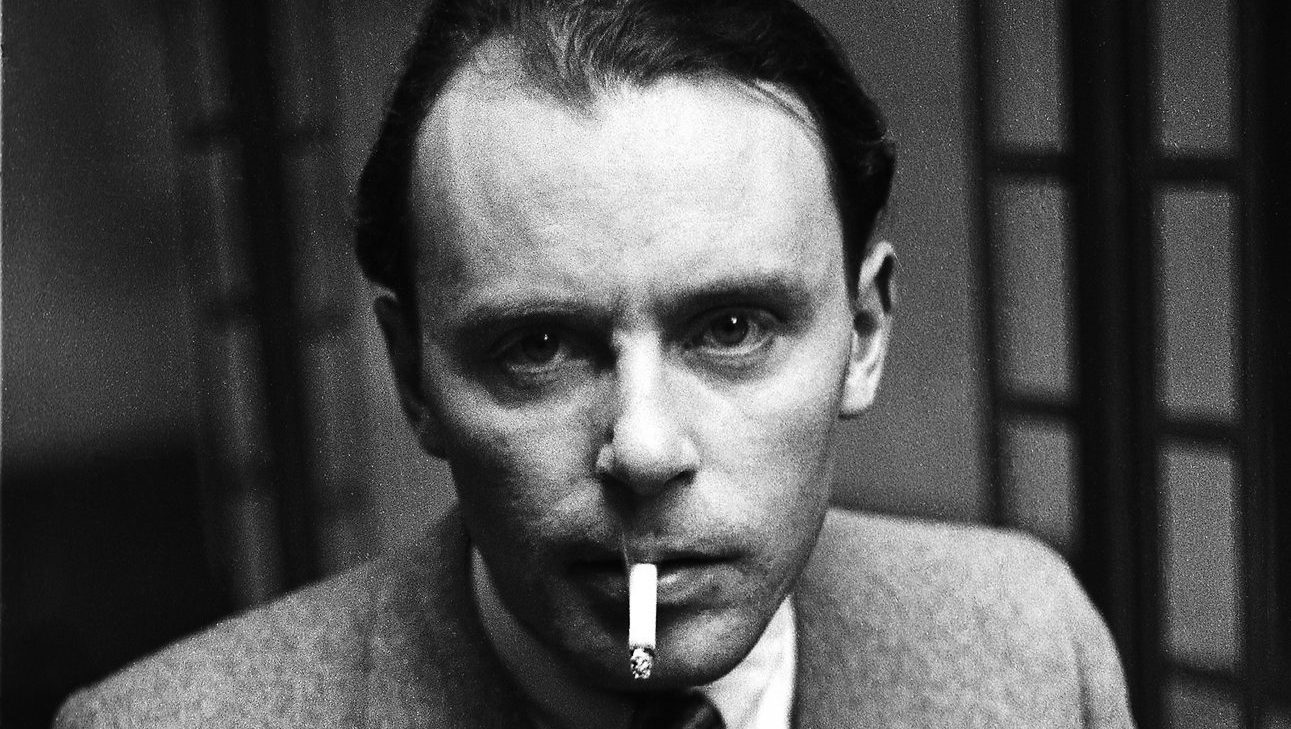

Mann himself was in many ways the embodiment of those literary times. An open critic of Nazism from the very beginning, he left Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933 and in 1936 crossed the Atlantic to the US. There he kept up his vigorous opposition to events back home, joining the US Army and serving in Italy towards the end of the conflict.

He was, like many of the writers featured in Heart of Europe, ultimately doomed. An outsider in Germany for his homosexuality and in the US for his communist sympathies, not to mention a lifetime of rejection by his father, Mann was a heavy drug user who was found dead from a probably accidental overdose of sleeping tablets in a Cannes hotel room in 1949, aged 42.

His most notable legacy is his novel Mephisto but Heart of Europe was arguably a greater achievement, serving as both a depiction of a moment in time and a proud exhibition of our continent’s unity and defiant spirit. As the American writer and activist Dorothy Canfield Fisher wrote in her introduction, “I think many other readers will find, as I did, that thus seeing all of Europe represented in one collection makes us more aware than ever before of the relation of Europe to the rest of the world”.

Heart of Europe is set out country by country, an overview by a literary figure from each preceding a selection of contemporary writing deemed representative of that nation. There are some big names here – Proust, Cocteau, Lorca, Svevo, Pasternak, Gorky, Rilke, Brecht – but most would be unfamiliar to modern readers.

The overall tone of the collection is understandably downbeat given the circumstances in which it was compiled. Displacement, exile and oppression are overriding themes and death is a looming presence.

“Portuguese letters are ailing,” is how Lusitano de Castro opens his introduction to the Portuguese section, noting the high preponderance of suicides among the nation’s writers and poets of the period, including António Nobre, who left behind the lamentation “What a sad thing, my lads, to have been born in Portugal”.

Introducing the German section, Franz Schönberner writes, “The history of literature, especially of German literature, knows many exiles, many refugees. But probably it has never before happened that a whole literature emigrated at the same time”.

Schönberner had been the editor of a satirical magazine that fell foul of the regime, forcing him like so many other German writers to escape to the US. He lists some of those who were not so lucky, like Theodor Lessing, assassinated by a bullet through the first-floor window of his study in Marienbad in 1933, and suicides like Stefan Zweig who killed himself in despair after escaping to South America. These tragic figures Schönberner declares passionately to be “yet more alive than Goebbels’ literary lackeys”.

The anger that fizzes from the page is inevitable given the times, but what thrums through Heart of Europe most powerfully is the irrepressible nature of literature. Europe has always been a continent of stories and as I sat leafing through the yellowing pages of this old hardback representing the thinnest of rings in the tree trunk of Europe’s literary heritage, I was reminded how stories, novels and poems define our continent, its nations and people.

The pieces crammed into just shy of 1,000 pages here represent just two decades of a centuries-old literary legacy and the quality is mindblowing. Some of it has inevitably dated, but most of the pieces still feel fresh – the Austrian writer Richard Beer-Hofmann’s exultant appreciation of Mozart, for example, brims with energy and passion, and while most anthologies – especially those with a limited scope – can vary wildly in quality, there are no passengers here.

It is tempting to look a little too hard for contemporary resonance, but our own troubled times can be detected in CP Cavafy’s poem Expecting the Barbarians, which lands almost as well today as it did in 1943. The poem describes a country preparing for imminent takeover with a mixture of prevarication and appeasement until it becomes clear the barbarians are not coming after all. This realisation leaves everyone solemn and even disappointed because “without the Barbarians, what is to become of us? After all, they would have been a kind of solution”.

The years between the wars were not exactly a golden age for European literature thanks in the main to the machinations of authoritarianism scattering its writers across the globe, but flicking through this 20-year slice of literary output assures me of just how powerful the legacy of storytelling is throughout our continent.

Ever since the Norse sagas, Europe has been a place of stories, a continuous line that includes the likes of Ibsen, Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Dante, Goethe, Cervantes, Boccaccio, Voltaire and Tolstoy. Today the range of high-quality European literature grows every year, with more and more of it brought to an Anglophone audience thanks to the current boom in excellent literary translation.

Revisiting Heart of Europe is a timely reminder that European literature will endure. Never still, it mutates and develops, expands and transforms, a thundering vehicle for an increasing range of voices that reflect the changing nature of our continent and the times in which they are written. There will always be challenges, but stories will endure. Stories are the best of us. The best of us will endure.

The Danish writer Karin Michaelis pays tribute to Hans Christian Andersen in Heart of Europe, for example. His work has long been infused in childhoods way beyond Copenhagen.

“There are several immortal writers who spread light in the darkest times of humanity,” she writes, “but there is only one Hans Christian Andersen. And if Denmark should sink into oblivion I wonder if Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytales would not be the last things to survive.”

Literature is not all about hardship and challenges. The best books become joyful landmarks in our lives, a dog-eared copy serving as a reminder of a time and a place that means something to us beyond being a great piece of work. My European life is peppered with these, from reading William Heinesen lying in a field on one of the more remote Faroe Islands to the discarded copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners I once picked up on the Viennese metro that caused me to do almost two complete circuits of the city.

Among all these boxes somewhere there is a copy of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther that I deemed an appropriate addition to my guitar case when I spent a couple of months busking round Germany. There is also a battered paperback of Bill Bryson’s Neither Here Nor There, which inspired my very first European odyssey as a gullible innocent with an Interrail ticket and not nearly enough changes of underwear.

The copy of The Bridge Over the Drina by Ivo Andric that someone gave me in an underground bar in Sarajevo at the end of a hot and boozy night putting the Balkans to rights is here, as are the poems of Arnulf Øverland – whose Vi overlever alt, “We Shall Survive”, a poem that helped inspire the Norwegian resistance, is included in Heart of Europe – in a collection purchased 250 miles above the Arctic Circle in Tromsø on a tipsy whim after a couple of eye-wateringly expensive beers and ignoring the fact I can’t read Norwegian.

That is before even considering the books I’ve been introduced to by having the immense good fortune to write about them here. We might have left the European Union, but a sliver of that gross idiocy is mitigated by having the continent at our fingertips through the pages of its literature. It has always been an immense privilege to bring you the best of it.

“Europe is a land of terrific changes, sweeping transformations,” wrote Klaus Mann in his introduction to Heart of Europe. “We must not visualise Europe as something finished and settled, a monument of its own glorious past but, on the contrary, as a dynamic organism, striving, struggling, sinning and atoning, still pregnant with terrific dangers, ample promises.

“Europe,” he added, “is a continent in the making.”