Aldo Moro was twice Italy’s prime minister. On May 9, 1978, when police found Moro in the boot of a Renault 4, riddled with 11 bullet holes, his body was no more than 400 metres from the spot where, 2,000 years earlier, Julius Caesar had been knifed.

Moro, who after his second term ended in 1976 became president of the powerful Christian Democracy Party, had been kidnapped on March 16, in Rome’s Via Mario Fani. He was being driven through town with a security escort when two cars suddenly blockaded the road. Armed terrorists attacked and the politician’s five-man security detail was massacred in a hail of machine-gun fire. He was bundled into a car and driven away.

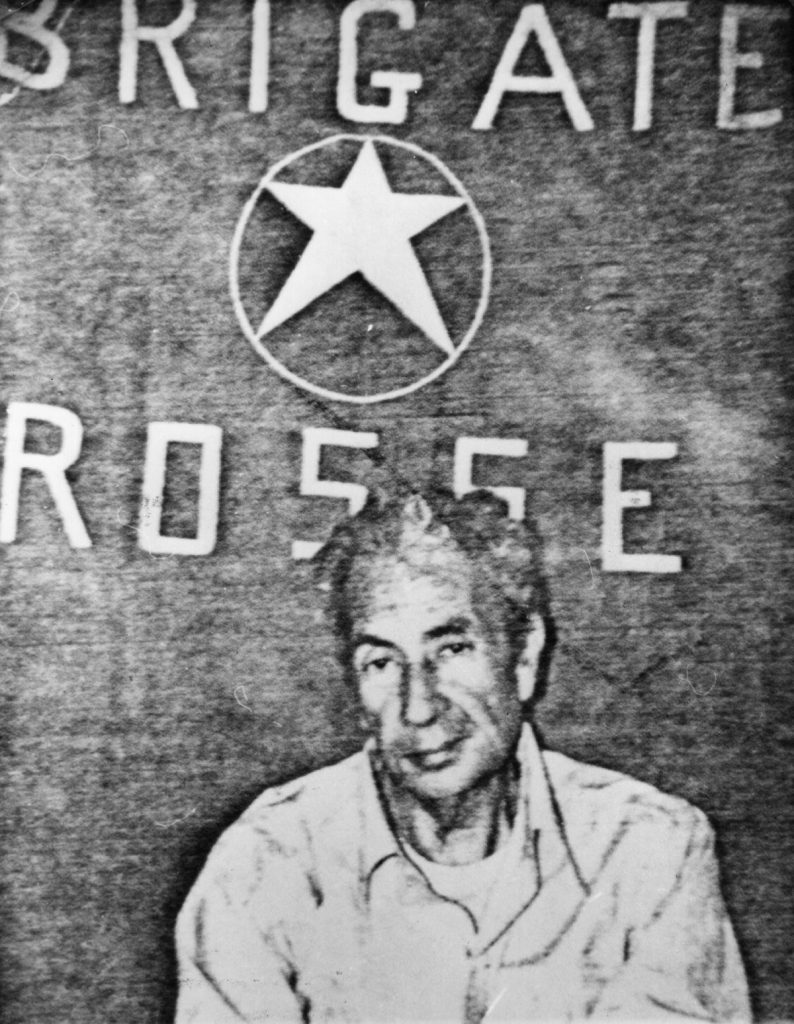

The abduction stunned Italy – and the world. A huge search operation ensued. Pope Paul VI, a personal friend of the former PM, offered to swap places with the abducted man. But the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse), the extremist left wing terror group that had snatched Moro off the street, had no time for holy men.

They were a product of the cold war, which had opened up huge political divides in Italy, where extreme political attitudes had entered the mainstream. The Italian Communist Party (PCI), openly funded by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, had won an astonishing 34.4% of the popular vote in the general election of June 1976, a result that had horrified the right, as well as Italy’s Nato partners. The communists were now the kingmakers. When combined with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), the two parties held more seats in both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies than Moro’s ruling Christian Democrats.

Then came the political decision that ultimately led to disaster – Moro decided to form a unity government with the communists, a move that he called his compresso storico, or “historic compromise”. But the extremists of the Red Brigades didn’t want the communists to do a deal with what they saw as Moro’s centre-left party. That, in their view, was a sell-out and could not be tolerated.

The Nixon White House was also not happy at the thought of Moro inviting communists into government, and it made its misgivings clear. Moro’s widow, Eleonora, testified that in early 1978, Henry Kissinger, together with an unidentified CIA official, met her husband. “Abandon your policy of bringing all the political forces into direct collaboration,” they told him, “or you will pay dearly for it.” Moro ignored this warning. A few weeks later he was kidnapped, on the very morning he was to sign the compresso storico into law.

The nationwide search for Moro involved more than 38,000 Carabinieri, military and secret services, and it lasted 54 long days. When Moro was found dead, the shock was terrible. But when it was revealed that he had been held prisoner in the very centre of Rome for the entire time, that shock was replaced by an overwhelming sense of failure. Having failed to find such an important hostage, who was being held right under their noses, the viability of Italy’s police and justice system was called into question.

The killing of Aldo Moro created a wave of conspiracy theories, which were not helped by the refusal of Italy’s right wing prime minister, Giulio Andreotti, to negotiate for his release. That invited the inevitable question, “why not?” And what’s more, how could such a famous individual be held in the centre of Rome for so long by a haphazard group of amateur revolutionaries? How could the police fail to track him down? How could they fail to identify a single witness who could lead them to the hostage?

It was often said of 1970s Italy that if anything had been executed with precision, skill, expertise and efficiency, then it could not, by any definition, have been Italian in origin. So if the plot was not Italian in origin, who had organised the abduction and murder? One of Italy’s sinister neo-fascist political groups, terrified that he might bring communists into the government? Or was it the CIA?

In the continuing absence of a defintive verdict, the last word goes to the Red Brigades. To mark 20 years since Moro’s death, Alberto Franceschini, one of the terrorist movement’s four founders, stated: “On this anniversary, I have the need to in some way understand what really happened. I don’t know whose hands were behind the scenes, Andreotti’s or Nixon’s, but I know we were part of a much larger game.”

Simon Gaul’s novel White Suicide, which begins with the kidnap of Aldo Moro, is available now from Whitefox Publishing