Inspired by a photo of a young, cool European couple in love, Backbeat has become one of the most admired and enduring film stories around the mythology of the Beatles. So much so that the movie has just celebrated its 30th anniversary with a London screening.

Bit of a shock, that, isn’t it? Thirty years. I remember it so well, when Backbeat came out in 1994, following a buzzy premiere at the Sundance film festival, the same edition that gave a screening to another British offering, a certain comedy called Four Weddings and a Funeral.

Obviously, the Hugh Grant romcom has become a classic while Backbeat, the tale of the Beatles’ formative experiences in Hamburg, directed by Iain Softley and starring Ian Hart and Stephen Dorff, has cemented itself as more of a “cult film”, though no less cherished for it.

I hadn’t seen the film at all in the intervening 30 years – weirdly, it is not yet available to stream here in the UK – and its story of youthful camaraderie and rock’n’roll adventure has an everlasting appeal, an energy fuelled by a sexy sense of exploration and the tantalising knowledge of what the future holds for these young men.

It helps, too, that the film’s story of Stuart Sutcliffe, the so-called fifth – or even sixth – Beatle, is still not particularly well-known to the new generations of the band’s fans. His legacy has been mainly left out of the recent hours of documentaries dedicated to the Fab Four.

But Backbeat is actually the heartbeat of the oft-neglected European influence on the band while Sutcliffe seems destined never to even attain the level of notoriety of Pete Best, who is most regularly labelled the “fifth Beatle” – a drummer, he was axed in favour of Ringo Starr.

In 1994, the story of Sutcliffe and his romance with photographer Astrid Kirchherr was barely recognised at all and Softley, who also wrote the screenplay to this, his debut feature film, was able to keep his discovery pretty much to himself.

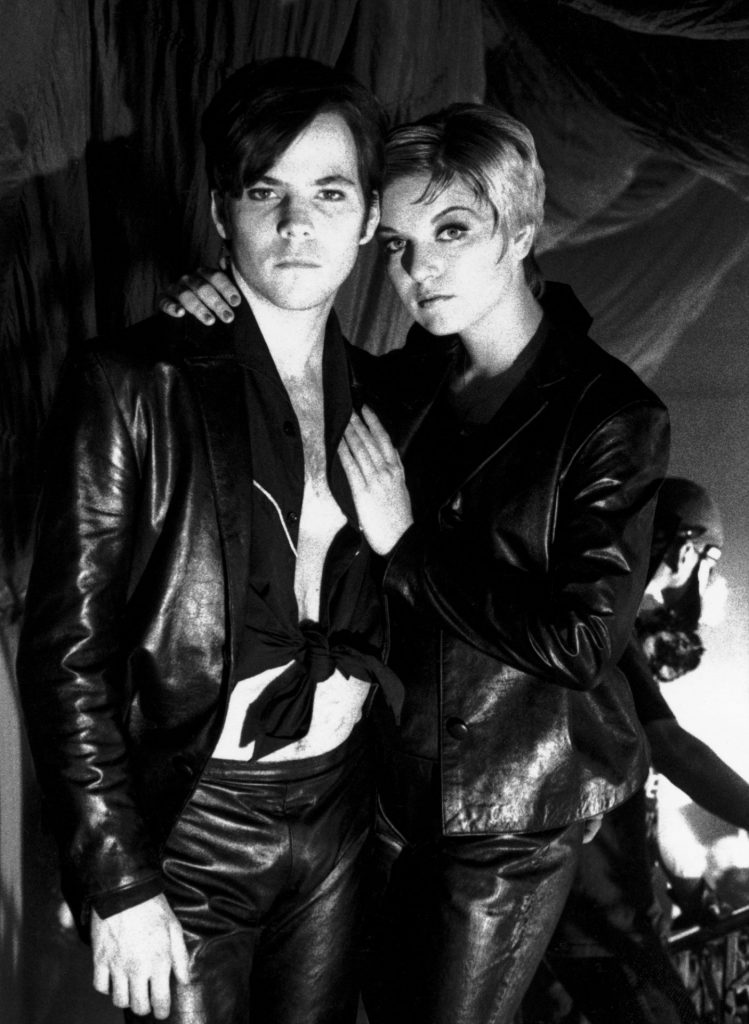

“I was transfixed by a photo I saw of Stuart and Astrid,” he tells me. “It was just so haunting, so full of yearning and mystery, like something out of a cool New Wave movie that hadn’t been made yet.”

Backbeat, then, is that film.

The photo sent Softley on a mission. As a documentary maker working at Granada Television in Manchester, he was well equipped to investigate, but says he always had designs on this particular story as a movie. He tracked down Stuart Sutcliffe’s mother in Sevenoaks, who put him on to his sister, Pauline, who eventually gave him Astrid’s phone number in Hamburg. Only it wasn’t the photographer’s home anymore, but that of an ex-boyfriend who only knew that Astrid, the woman who took the first shots of the Beatles, now worked in a bar.

“I was on a plane to Hamburg within days,” says Softley. “I just knew this would be something I’d have to track down and be a part of, and when I did contact the bar and finally get Astrid on the phone, I was shocked how readily she invited me to visit her at her apartment. I’d built up this air of mystery, but in the end, she couldn’t have been more helpful.”

In fact, on that first visit, Astrid invited Klaus Voormann over as well. Voormann had played bass on John Lennon’s Imagine album, and had a successful career as a session musician, playing on Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain. He also won a Grammy for his design of the Revolver album cover. (Euro-synth pop fans and aficionados of the old Casio VL-Tone might like to know that he also produced the 1982 hit Da Da Da for German group Trio)

“So suddenly, right in front of me, were two people who were intimately involved in the story of the Beatles and it became clear to me just how much the lads had been influenced by their time in Europe and the artist hipster scene in Hamburg, particularly John Lennon. But for the story of Stuart Sutcliffe, art was the bigger appeal.”

So Backbeat becomes about a young man’s decision to leave what will soon become the world’s biggest band to pursue the path of love and follow what he believes is his true calling as an artist. Not to spoil it, but Sutcliffe stays behind in Hamburg when the Beatles are forced back to Liverpool. He suffered from undiagnosed brain issues and died in 1962, leaving behind an art collection that has taken years to be appreciated.

It’s really a film about taking the leap, making the risky choice, and there’s a compelling sense of narrative throughout, as John and Paul become more determined for musical success while Sutcliffe is drawn to the “real bohemian” circles of Astrid and Klaus, even going on to enrol in the Hamburg art school where he is tutored by pop artist, sculptor and Tottenham Court Road tube mosaicist Eduardo Paolozzi (who would later design the inside album jacket of Red Rose Speedway by Wings).

Meanwhile, Astrid also designed the haircuts that changed the world, trying out the famous moptop cut on Stuart, then George, and finally persuading the others to ditch the rockabilly quiffs for the look that, among many other factors, made them famous.

Astrid also took some of the very first publicity shots of the band, framing them against a dilapidated fairground ride in stark black and white, very moody and 1960s European.

“I think this artistic interaction between cultures is rarely recognised when talking about the Beatles,” says Softley. “But it was only a few years later and they’d be using Peter Blake for perhaps the most famous album cover in history with Sgt Pepper’s, so that art influence was clearly there. And their films, although made by an American director in Richard Lester, have that European New Wave, free-wheeling element.”

Backbeat features plenty of European film references. Astrid takes Stu to see the Jean Cocteau movie Les Enfants terribles (1950) and Softley says much of the decor style in Astrid’s apartment was inspired by Cocteau theatre sets. He also cites the use of colour in Jean-Luc Godard movies such as Le Mépris and Pierrot le Fou as influential (although these weren’t released until after the Beatles had returned from Hamburg), as well as the more mixed palette of Jacques Demy’s musical Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, which balances drab reality with bright aspiration.

“Of course Astrid’s photos were key, too, but one of the real inspirations in the club scenes were the paintings of Toulouse Lautrec,” he says. “We lit the Hamburg club stage, the Kaiserkeller, from the ground up, as if we were using gas lamps at the front of the stage. That’s what really gave the band on stage the grungy quality we were looking for.”

The use of grunge extended into the sound of the movie, too, resulting in the assembly of what Softley calls a “grunge supergroup” to play the songs. Under the musical direction of legendary producer Don Was were musicians including Dave Grohl, then with Nirvana, on drums, Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth on guitar, Mike Mills from REM on bass and Dave Pirner from Soul Asylum on vocals, belting out Long Tall Sally, Money (That’s What I Want) and Rock and Roll Music in the style of wild teenage band let loose for the first time to an ecstatic audience.

“John Lennon once said: ‘We were never as good as we were in Hamburg’,” says Softley. “And while you can get bootlegs of them in Hamburg and can feel the buzz of it, the sound quality is dreadful so we really needed that energy but also to showcase the growing musicianship and connection.”

For all the recent music films that have suffered from not having access to the protagonist’s catalogue (such as the Jimi Hendrix biopic, All Is by My Side, with André 3000, and Johnny Flynn’s early Bowie film, Stardust), Backbeat made a virtue of not having any Beatles rights.

Producer Finola Dywer, whose first feature this was too, recalls the somewhat colourful genesis of it, recalling the late British film exec Nik Powell being hit with an idea. “He was on the loo, reading a music magazine,” she says. “He came bursting back into the office waving around this article and yelling that Don Was should be the man to get the band together. Don had worked with Dylan, the B-52s, Elton John, Bonnie Raitt and Iggy Pop, but he agreed to do it if he could also do the film’s score, which he’d never done before. Of course, he ended up winning the Bafta for it.”

Dwyer also remembers the film’s LA premiere to which Was, who was producing The Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge album at the time, brought along Keith Richards. “So there were no Beatles, but there was Keith,” she recalls. “About halfway through I went out of the movie with Don to smoke a cigarette – I think he had a joint – and he growled: ‘Keith is still awake, so we must be doing OK.’ That was some seal of approval.”

The music struck a chord in the nick of time, really. While America still revelled in the rock’n’roll of grunge, Britain was about to respond with Britpop and the Beatles playing in Backbeat caught that moment, just as Blur and Oasis were breaking through.

Softley also points out that just a few months later, popular taste was shifting forward, to the growing influence of dance music. His follow-up film, the cyber-crime thriller Hackers in 1995, featured the electronica and techno of the Prodigy, Underworld, Leftfield, Carl Cox and Orbital. “We got there before Trainspotting,” he sniffs.

“There was some feeling of a cultural revolution in Soho 30 years ago,” says Softley. “You could sense a British film industry about to be revived due to the new funds from the National Lottery and meanwhile restaurants were spreading on to the pavements. It was a reaction to the Thatcher laws on gathering and repetitive beats and the Poll Tax. I think Backbeat happened to hit that zeitgeist and capture the sense of adventure and rebellion in the story of these working-class boys who were tough and edgy and determined to make it when they sniffed success.”

The film reveals a remarkable steeliness in Paul (Gary Bakewell) and George (Chris O’Neill) and particularly in Ian Hart’s superb John Lennon, who initially sticks up for his best mate and fellow art student Sutcliffe but who comes to realise the band is better off letting him go. There’s more than a frisson of jealousy over the beautiful Astrid, too, played as she is by German-born actress Sheryl Lee, hot off her role as Laura Palmer in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks.

Sutcliffe was played by Stephen Dorff, a relatively unknown American actor whose casting – and Scouse accent – initially drew criticism but who brought an alien, otherness to the character, giving Stu a sense of brooding mystery and detachment. While Paul McCartney opined that his character wasn’t given enough rock’n’roll songs to sing in the film, he did single out Dorff’s performance for really capturing the essence of Sutcliffe.

Producer Dwyer says that the makers were particularly nervous about the reaction of the real-life Cynthia Lennon, who was played by Jennifer Ehle. “We agreed to show her a pre-premiere screening in Soho, just to be safe, and she insisted on a couple of stiff drinks beforehand even though it was before lunchtime,” remembers Dwyer. “She did come out in tears and I was petrified for a moment, but she loved it, and then agreed to bring Julian to the premiere, telling him: ‘You’re going to meet your dad tonight’.”

Dwyer also remembers filming in Hamburg, on the street just off the Reeperbahn, where the KaiserKeller is still situated, on Große Freiheit Strasse in the St Pauli district. She tells how they had struck a deal for all the neon lights to be kept on but just as they were about to shoot the street scenes, all the sex show windows went dark until the film-makers stumped up more cash to pay the girls.

Backbeat thus works its nostalgia on several levels. You could see it as a snapshot of the British film industry in 1994 and a chance to remember where you were when you might have seen it, or read about it, as it became a bit of a tabloid favourite, as most of producer Stephen Woolley’s films did – remember Absolute Beginners in 1986 caused a storm (Iain Softley directed the music video for the Style Council’s Have You Ever Had It Blue, which featured in that film).

But it’s also about the 1960s and the beginning of a new age, a youth culture, and the beginning of a group of lads who made history and who continue to hold a fascination, in music and on screen. It’s a film that can inspire teenagers everywhere that they can do it too, and it’s a tribute to one of them who was strong enough to decide he could make his own little piece of history.

Backbeat cinema screenings continue throughout its anniversary year. The film is available now on BluRay and DVD.