The first art historian died 450 years ago this year. Giorgio Vasari was an artist in his own right who cultivated his access to the influential Medici dynasty, dedicating the first volume of his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects to Cosimo I. His Vite became the model for successive less partial and more in-depth studies. Nonetheless, the practice of writing up the life and work of individual creators began with Vasari, whose three volumes continue to illuminate and entertain.

Born in Arezzo, Tuscany, where many exhibitions and events this year mark his anniversary, he had an undisguised preference for artists trained or based in Florence, 70km away. Justifiably a little vain, often inventive in his narratives, he was personal friends with some of his subjects and colleagues, among them Michelangelo. “Giorgio, if I have any intelligence at all, it has come from being born in the pure air of your native Arezzo…” Vasari recalls Michelangelo saying, in his chapter on the painter and sculptor who was, in reality, born in a village a full day’s walk away from Vasari’s home town.

But in the same entry he describes with drama and admiration the placing of Michelangelo’s great statue of David, in 1504, in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. “To be sure, anyone who sees this statue need not be concerned with seeing any other piece of sculpture done in our times or in any other period by any other artist,” he writes.

The white heat of artistic activity in Florence in 1504 is the subject of a new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London that focuses on the conjunction there, as of three orbiting planets, of three creative giants: Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), born 30km west of Florence, Michelangelo (1475-1564), and a new rising star, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), known as Raphael.

The dynamics between the three oscillated from rivalry to admiration, imitation being the sincerest form of flattery, and the overlap was short-lived, as projects outside Florence attracted the greatest artists of the age. Nevertheless, there was a moment when Michelangelo and Leonardo were to have worked in the same great debating chamber, the Sala del Consiglio, in the Palazzo Vecchio, which rises to this day behind David (now in replica, the original safely tucked inside the city’s Accademia). Here Vasari enters the story again, for with his brushes rather than his pen in his hand, he completed here in 1565 a great cycle of frescoes celebrating Florentine victories over the rival states of Siena and Pisa. He was working on the site of intended works by Michelangelo and Leonardo, neither of which materialised.

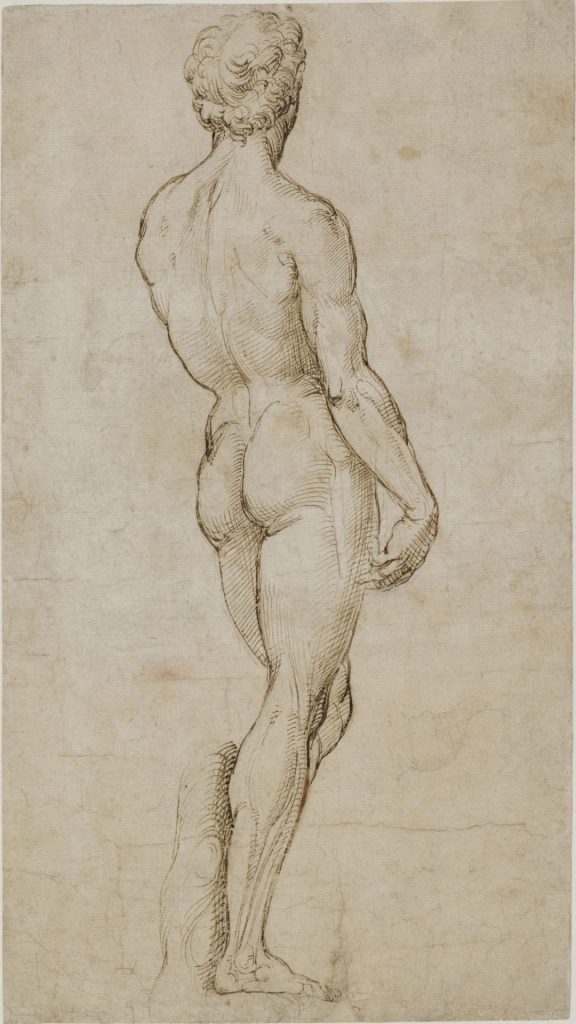

Commissioned to mark Florence’s supremacy at the Battle of Cascina, Michelangelo never went beyond the drawing stage. In his curious design, rather than showing the mighty Florentine troops in action, he picked the moment when the rallying call catches them off guard, bathing. They hurry to don their battle dress, struggling to drag awkward garments over damp skin. In the bulging muscles, straining sinews and extravagant gestures we see the seeds of his ceiling and altar wall compositions at the Sistine Chapel in Rome, to which he hurried from Florence, summoned by Pope Julius II.

The Battle of Cascina (‘The Bathers’), c1542. Image: Earl of Leicester and the Trustees of Holkham Estate

For his part, Leonardo set to work on depicting the Battle of Anghiari, a skirmish between Florentine and Milanese forces in 1440 which is said to have concluded without bloodshed. That wasn’t going to stop Leonardo knotting a cat’s cradle of panic-stricken horses and riders. Unlike Michelangelo, he started work on his section of wall, and scholars are pretty sure that he worked on the far right of the wide hall as councillors entered, roughly where visitors arrive today, while Michelangelo was assigned the left. But Leonardo was not a fresco artist, and so experimented with oils and wax, which ran and stayed wet. Lighting braziers to accelerate the drying process only caused more melting.

We know the two artists’ intentions, thanks to copies made at the time. In the case of Michelangelo, the design for his bathers was captured by Bastiano da Sangallo, in an oil panel now in the collection of Holkham Hall, Norfolk. A copy of Leonardo’s design made in the 1550s was enhanced by Rubens, whose magnificent chalk, pen and ink version is in the Louvre. Both are loaned to the RA for this exhibition, which looks in forensic detail at this doomed project, with sketches of men and beasts aplenty.

Vasari knew all about the Michelangelo/Leonardo project when he set to work decorating the newly extended hall, and left behind a tantalising mystery. In the area where the Battle of Anghiari should have been visible, Vasari painted an elaborate battle scene, but first of all he created a cavity, unlike elsewhere in the room, between the original wall, and his own, new support. Secondly, he put the teasing “seek and ye shall find” legend CERCA TROVA on a banner born aloft by helmeted soldiers. Seek and ye shall find what? Leonardo’s original mural? A hole drilled into the cavity a decade or so ago revealed nothing.

But, as Per Rumberg, co-curator of Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c1504 points out, art analysis technology has moved on in the intervening years. Today’s techniques might yet yield glimpses of Leonardo’s hand, but, warns Rumberg, “If there’s anything there, there isn’t much…”

As Leonardo abandoned the job, he placated the city fathers with what today is known as the Burlington House Cartoon – The Virgin and Child with St Anne and the Infant John the Baptist. This star of the National Gallery, which acquired it from a then hard-up Royal Academy in 1962, is loaned back to the RA to be displayed near two works with which it shares a forceful relationship. With a bit of shuffling, it is possible to see in one glance the Cartoon, Michelangelo’s low relief known as the Taddei Tondo, and the young Raphael’s oil painting of the Virgin and Child, dubbed the Bridgewater Madonna.

The Michelangelo relief came first, rising to the challenge of a circular marble sculpture by placing right across the composition a wriggling Christ child, one who appears both fascinated and repelled by the goldfinch held towards him by the older child, John. The bird, with its flash of red feathers, represents the Passion. Leonardo in turn, two or three years later, depicts a twisting child, as did Raphael soon after.

Vasari probably got it wrong when he recorded that Leonardo was designing for a friary. Vasari, whose achievement in quite simply creating the discipline of art history cannot be overestimated, may on this occasion have muddied the waters by confusing or conflating two images. But his admiration for Leonardo’s drawing is unmistakable. The work “not only amazed all the artisans,” he wrote, “but, once completed and set up in a room, brought men, women, young and old to see if for two days as if they were going to a solemn festival in order to gaze upon the marvels of Leonardo which stupified the entire populace”. Rumberg now believes that the Cartoon was intended as a design for the centre of an altarpiece on a wall in the Sala del Consiglio facing the battles of Cascina and Anghiari. If so, it was something of a peace offering, possibly unsolicited, after the failure of Lenoardo’s The Battle of Anghiari.

The young Raphael, briefly overlapping in Florence with the older men, absorbing their work, and developing his own style, was no Florentine, but nonetheless Vasari was unstinting in his admiration. “How generous and kind Heaven sometimes proves to be when it brings together in a single person the boundless riches of its treasures and all those graces and rare gifts that over a period of time are usually divided among many individuals can clearly be seen in the no less excellent than gracious Raphael Sanzio of Urbino,” runs the opening paragraph of his biography of the fast-learning artist.

Raphael’s stay in Florence was fleeting: his short life moved faster than most. Losing both parents by the age of 11, he worked in Umbria under Perugino, leaving masterpieces in his first training ground, Citta’ di Castello. He fetched up in Florence late in 1504, at the age of 21, staying off and on until 1508, soaking up the city’s art and atmosphere and leaving

a trail of increasingly sophisticated religious works before answering the call to Rome.

Upon his arrival, Michelangelo’s David had been in its place before the Palazzo della Signoria for a matter of weeks. Leonardo had been on the committee that decided its location, and Raphael drew it, from behind, shrinking its hands. Three of the greatest artists who ever lived briefly circled round each other in Florence in 1504, then went their separate ways.

Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c1504 is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until February 16

Vasari: The Theatre of Virtues is at the Municipal Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art and Church of Saint Ignazio, Arezzo until February 2

Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists, translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella is published by Oxford World’s Classics