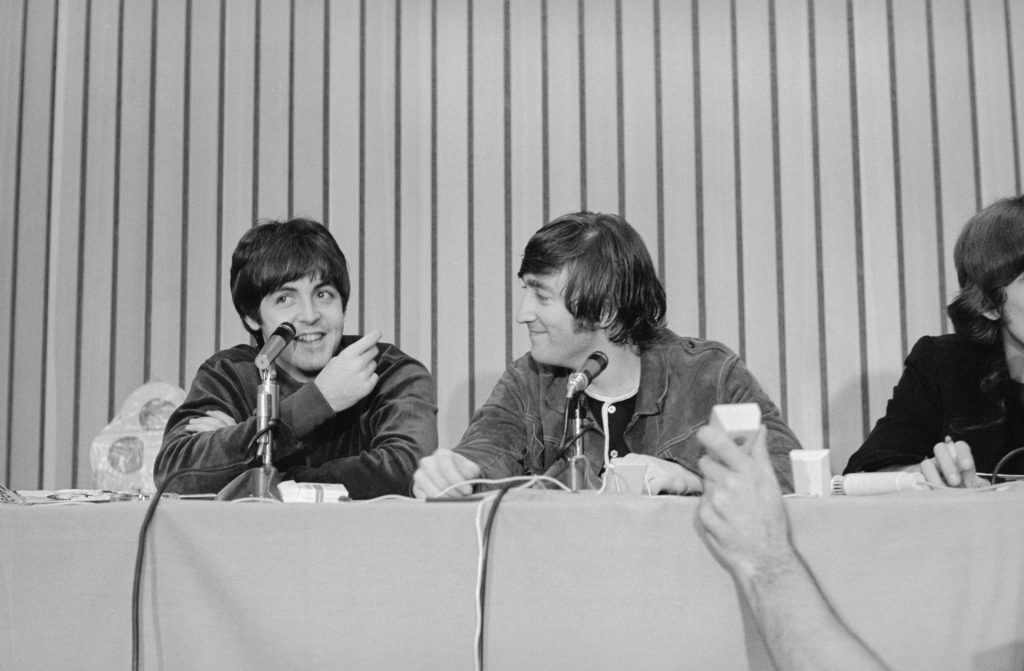

On Saturday January 27, 1968, John Lennon was interviewed at Kenwood, his home in Weybridge, Surrey, by Kenny Everett for BBC Radio 1. The Beatle sounded woozy, possibly stoned, rambling about “all the swinging England set today” and barely bothering to explain the meaning of Strawberry Fields Forever: “It’s pretty straightforward, isn’t it?”

In other news that day: I was born in Lewisham Hospital in south London.

That’s how much we know about the Beatles: pretty much every day of the seven years and seven months that Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr were together is accounted for online, often in exhaustive detail. Hundreds of books have been written about the Fab Four, and scores of documentaries produced.

More than half a century since McCartney made the Beatles’ split official in a press release in April 1970, the group still seems to connect to everything, everywhere, all at once. Earlier this month, Sir Sam Mendes walked out on stage at CinemaCon 2025 in Las Vegas with the four actors who will play the band members in four biopics to be released in April 2028: Paul Mescal (McCartney), Harris Dickinson (Lennon), Joseph Quinn (Harrison) and Barry Keoghan (Starr).

On April 11, One to One: John & Yoko, the long-awaited IMAX documentary made by Oscar-winning director Kevin Macdonald, opens in selected cinemas (as it happens, I was at school in Scotland with Kevin when we were very young: told you the Beatles connect everything).

Meanwhile, Ian Leslie’s wonderful new book, John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs, is storming up the bestseller lists. Re-examining perhaps the most famous musical writing partnership in history, he seeks, through the lens of 43 songs, to understand the complex relationship between “two teenage boys [who] invented their own future, and, in doing so, our present”, and to dismantle the “public differentiation in which McCartney came to be regarded as the sentimental balladeer, Lennon the abrasive rocker”.

As Leslie frames it: “Their friendship was a romance: full of longing, riven by jealousy. This volatile, conflicted, madly creative quasi-marriage escapes our neatly drawn categories, and so has been deeply misunderstood.” You can listen to him talking to TNE founder and editor-in-chief, Matt Kelly, and me on the episode of The Two Matts posted on April 1: do check it out.

The question that lingered after our conversation was the unique and uniquely emotional role that the Beatles play in the lives of Boomer, Gen X and Millennial men. This devotion is less apparent in Gen Z, though the fragmented nature of the musical landscape into which that age cohort was born means, by definition, that it has fewer shared cultural allegiances on the scale that was normal before Spotify and iTunes.

But it is men. Of course, millions of women today love the Beatles’ music, iconography and folklore. The engine that drove the band to initial superstardom was powered by screaming girls. But a straw poll of female friends confirmed my suspicion that, in 2025, the contemporary fixation with the band – the sense of enchantment that made the release in 2023 of Now and Then, “the last Beatles single”, such a big deal for some of us – is a predominantly male phenomenon. As one of them put it me: “The music is great but the way you blokes obsess over it… it’s worse than football”.

If that is so – why? I think Leslie’s book goes a long way to explaining the enduring function of the Beatles in the masculine consciousness. As he puts it: “we have trouble thinking about intimate male friendships… We’re thrown by a relationship that isn’t sexual but is romantic”.

Friendship between men has always been a staple theme of western literature and drama: think of Achilles and Patroclus in The Iliad; Montaigne’s great essay De l’Amitié (quoted by Leslie); Hamlet and Horatio; David Copperfield and James Steerforth; Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (“I think of Dean Moriarty”); Withnail and I (“I shall miss you, Withnail”); Andrew O’Hagan’s Mayflies.

Yet as Lennon remarked in 1967: “Talking is the slowest form of communicating anyway. Music is much better”. Which was his way of saying that, in the songs he wrote with McCartney, he expressed emotions, ideas and dreams that were harder – or impossible – to convey in language alone.

As competitive as their relationship could be, pathologically so at times, its greater significance lay in the radicalism of the convergence. As Leslie puts it: “the distinct and thrilling aesthetic effect of two men who share the same ‘I’ – the same consciousness… how two people can slip in and out of each other’s subjectivity: the way we internalise the voices of those we know and love”.

Anyone who has watched Peter Jackson’s glorious three-part documentary The Beatles: Get Back (Disney+) – using footage and audio from the production of Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s Let it Be (1970) – can attest to the extraordinary, telepathic bond that persisted between Lennon and McCartney even at this late stage in the band’s life, when relations were strained and collective exhaustion was setting in. There is still a private language of nods, smiles, and verbal cues between the two men.

In their music, they started with cover versions and, by the end, had completely redefined what pop could aspire to be. One of their most important achievements was to record singles like She Loves You and Hey Jude, each of which, as Leslie writes, was “that unusual thing, almost unique in the annals of pop: a song sung by a man to a close male friend”. Hey Bulldog on the album Yellow Submarine “is a shout of empathy – if you’re lonely you can talk to me”.

McCartney called it their “heightened awareness” of one another. Lennon went further, saying: “It’s like you and me are lovers”. Did he mean it literally? Yoko Ono speculated to her husband’s biographer Philip Norman that he felt a sense of sexual rejection: “I knew there was something going on here”.

But as McCartney later made clear, powerful romantic attachment and sexual desire are not necessarily the same: “I’m sure [Beatles manager] Brian [Epstein] was in love with John. We were all in love with John, but Brian was gay, so that added an edge”.

Contrast nuanced reflections like that with the crude, aggressive language of today’s so-called “manosphere”. Jordan Peterson likes to be thought of as a serious psychologist and, latterly, scriptural scholar. That doesn’t stop him from saying something as bone headed as: “Toughen up, you weasel.”

Which is mild stuff compared to the misogynistic poison hosed online by Andrew Tate: “Weakness is the most disgusting quality a man could have”; or: “Action is the only way you’ll progress. Not talking. Not planning. And not reading books.”; or: “Moody females steal your power. It’s dangerous for a man. A man must remain focused”.

It is possible to overstate the power of such self-styled “influencers”. But it is also too easy to be sanguine about the wrong turn that contemporary masculinity has taken in an age with a desperate shortage of decent male role models, decrepit guard-rails and an insidious counter-narrative that tells boys they are born with original sin and are therefore irredeemable.

The Beatles showed that it is possible – essential, in fact – to be both masculine and emotionally intelligent. Despite the androgynous haircuts, they were definitely, unambiguously blokes: Scousers in tailored suits; antic silverbacks rampaging across the veld of cultural history.

They were the best gang of the lot in a decade in which England produced the best gangs on the planet: the Beyond the Fringe quartet; the Rolling Stones; The Who; the 1966 World Cup-winning team; and, creeping in under the wire in 1969, the Monty Python troupe. (To be clear, great gangs don’t have to be male: the most culturally important gang of the Nineties by far was the Spice Girls)

But the Beatles were also the gang that produced songs as emotionally vulnerable as If I Fell, Yesterday, All You Need Is Love, Ticket to Ride, In My Life, We Can Work It Out, Nowhere Man, and many more. Has there ever been a greater or more candid exploration of loneliness than Eleanor Rigby?

Please note: McCartney was only twenty-three when he wrote it. In truth, no soul that young should be so sensitive to suffering and so bruised by life as to come up with lines like: “Father Mackenzie/ Wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave/ No one was saved”. But it is miraculous that he did.

Do I think the behavioural problems of boys and men today would be solved if there were compulsory classes on Rubber Soul and Sgt Pepper? Of course not. Were the Beatles, as individuals, paragons of sensitivity and gentleness? Self-evidently not.

The optimism of Getting Better is much reduced by Lennon’s shocking admission that “I used to be cruel to my woman,/ I beat her/ And kept her apart from the things that she loved”. Before meeting Linda Eastman, to whom he was married for 29 years, McCartney was a careless philanderer, whose private life was very much at odds with his cherubic public persona.

It is important, in other words, for even the most obsessive Beatles fan to maintain some perspective. They were not saints, and their music will not save the world. As it turns out, in 2025, love is not all you need. Truth is just as important, as is the courage to stand up to autocrats and bullies.

But the idea of the Beatles remains one of huge and constructive power. In a collaboration of daunting intensity, velocity and industry, they showed how, even in insanely competitive circumstances, men can learn to interact, communicate, create, and, in times of trouble, provide a load-bearing wall against one another’s disintegration.

We inhabit a world of hyper-individualism, in which the young are (metaphorically) prepared for do-or-die, single-album solo careers. They are taught far too little about cooperation, the inevitability of failure, the need to be resilient and agile, even as employment is ever less secure, and people live ever longer. When I’m Sixty Four… sure, but what about eighty-four?

They need to be shown that very few pursuits are, in fact, zero-sum games. To return to the metaphor: they should be prepared for life in a band; many bands, in all probability. Come Together may be one of Lennon’s Jabberwocky-style nonsense songs (“He bag production, he got walrus gumboot”), but its refrain is still a good principle for a life well lived.

In our interview, Ian Leslie said that one of his objectives was to “refresh our astonishment” at the achievement of Lennon and McCartney. This is emphatically not a question of nostalgia. Celebrating skiffle is nostalgia. Celebrating the Beatles is to commune with and participate in a modern cultural myth.

The greatest music burrows into your bones and stays there forever. Why it does so is probably beyond rational explanation, just as creativity itself ultimately defies all forms of analysis. All we can attest to with certainty is that it means as much as it does, and hope that it does so a century from now.

I remember the chilly morning of December 9, 1980. I was 12, waiting for the school doors to be opened; and somebody had got hold of the paper (“I read the news today, oh boy”), found out that John Lennon had been murdered overnight in New York, and rushed over to tell us (don’t forget: no phones, web, news alerts back then).

It was shocking enough to silence us all, for just a moment. It was as if history had grabbed us, very briefly, by the collars of our jackets to deliver some dimly understood lesson: about the brutal caprice of the big world outside; the preciousness of friendship; and the ultimate fragility of all things.

And somebody spoke, and I went into a dream…