Overcast and quiet, the morning of Thursday August 23, 1973 in Stockholm’s Norrmalmstorg Square in the heart of the financial district was unremarkable.

However, just after 10am, the peace was shattered when a young man wearing makeup, a ladies’ wig and a pair of sunglasses entered the Kreditbanken building, pulled out a sub-machine gun from under his coat, fired off a round into the ceiling and shouted “The party starts! Down on the floor!” There was understandable panic. Some who were close enough ran for the exits, others did as the gunman said.

The perpetrator was Jan-Erik Olsson, a Swedish safe cracker out on temporary release from a three-year sentence for grand larceny. After a brief shoot-out with some police who had made their way into the six-storey building through back entrances, Olsson took control of the lobby.

Then he made his demands. He wanted 3 million Swedish crowns (about $4,000,000 today), a car and for Clark Olofsson, who had been a fellow inmate at Kalmar Prison, to be brought to him.

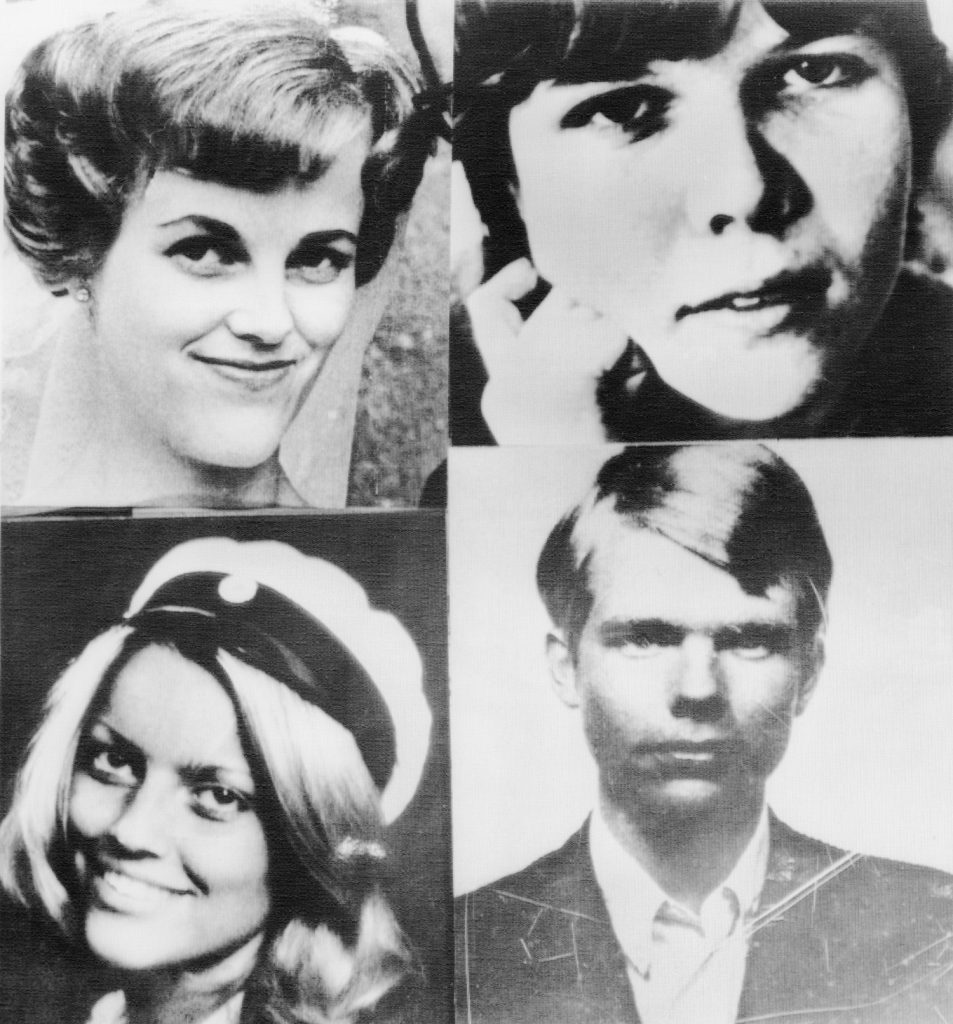

Olofsson was a charismatic counter-culture figure and Sweden’s most well-known criminal. The police acquiesced in the belief that he could help them achieve a peaceful resolution. Indeed, Olsson began releasing hostages in return until just four remained: Kristin Enmark, Birgitta Lundblad, Elisabeth Oldgren and Sven Safstrom. Then he demanded that Olofsson join the party.

Over the next six days, the country watched on, as enthralled as it was shocked. At the time there were just two TV channels in Sweden, and both provided live coverage of the drama almost to the exclusion of all else (the general election less than a month away hardly got a look in). At its peak, the conclusion to the robbery, more than 73% of the population were glued to their sets.

During the stand-off, the two criminals and their four hostages began to form an unlikely bond, random acts of kindness from the two criminals endearing them to their captives. Olsson wiped away Oldgren’s tears and apologised to Lundblad for inflicting on her a trauma that made her take up smoking again.

By contrast, the hostages began to develop antipathy towards the police, fearful that any attempt to end the siege would lead to their deaths. In a live radio interview, Enmark claimed that the authorities were playing with their lives. “They don’t even want to talk to me, who is the one who will die if anything happens,” she said.

Thus, when Enmark and Lundblad were allowed to go to the toilet on their own and both saw police officers hiding in the bank, neither took the opportunity to escape. “I was part of a group,” Lundblad said later, “there didn’t seem to be anything I could do about it.”

The bond only strengthened when the police locked the captors and their captives in a vault into which they had withdrawn. Olofsson found a phone and allowed the hostages to call home, consoling Lundblad when she couldn’t reach her parents. As they grew increasingly hungry, Olsson shared three pears he had kept hidden, dividing them equally between all six of them. “That was our world,” said Enmark later. “We were in the vault in order to breathe together, to survive. Whoever threatened that world was our enemy.”

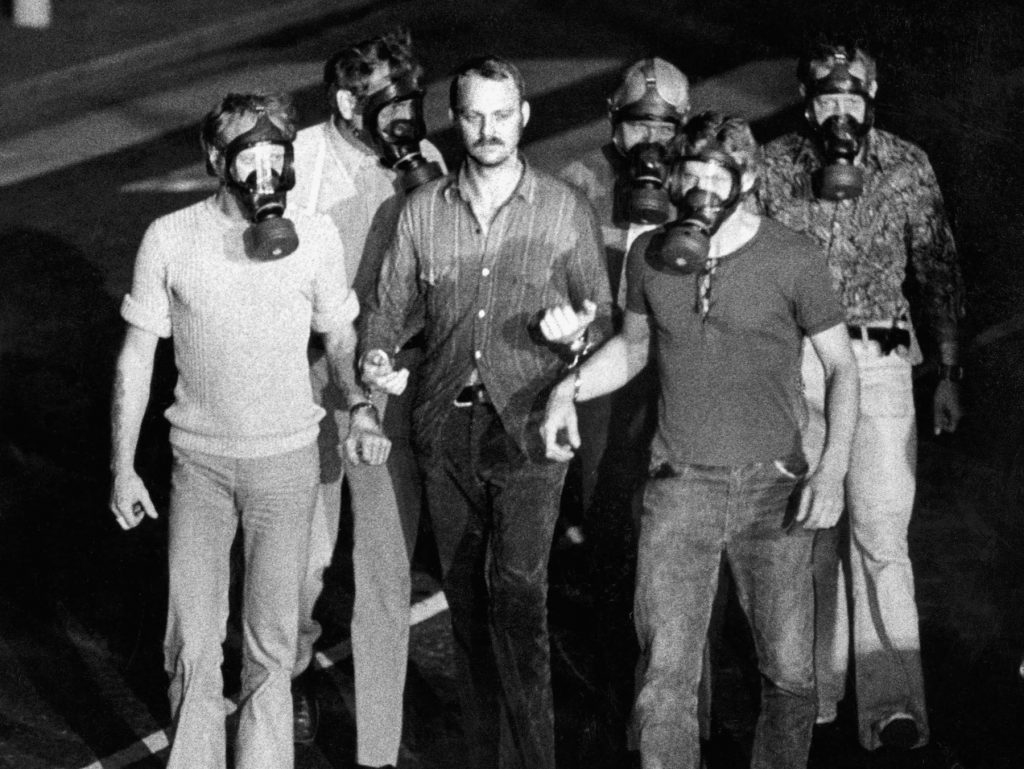

Olsson and Olofsson eventually surrendered on August 29 after the police pumped teargas into the vault. The hostages were ordered to leave first, but they refused to do so, believing that if they did their kidnappers would be gunned down. Instead, to the astonishment of those watching, Enmark and Oldgren embraced their kidnappers. “Don’t hit him!” Enmark shouted as police roughly shackled Olofsson to a stretcher. “We’ll see each other again,” she told her handcuffed captor.

The following day, Lennart Lionggren, the doctor in charge of their treatment, described the hostages’ condition as being similar to the shock experienced by victims of war. In particular, the seemingly irrational bond they had formed with their captors came under intense scrutiny; it defied all logic. Consultant psychiatrist Nils Bejerot who had been on the scene advising police explained it as “Norrmalmstorg Syndrome”.

Significantly, however, Bejerot was the cause of at least some of the hostages’ distrust of the police. Enmark had criticised him while talking to radio journalists from the vault. In turn, he had refused to speak to Enmark while she was held captive. Consequently, both she and Oldgren refused to meet him after their release. Furthermore, he never tried to speak with Safstrom, the only male hostage.

Stockholm Syndrome, as it became known, gained wider recognition when American heiress Patty Hearst was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) in 1974. During the following 19 months, Hearst changed her name and took part in a series of bank robberies, infamously being caught on security camera footage toting a machine gun. She was eventually arrested and although the term “Stockholm Syndrome” was never mentioned during her trial, her defence was based on the same rationale, catapulting it into widespread consciousness.

At the time, Professor Frank Ochberg, who was one of the pioneers of our understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder, had been assigned to the National Task Force on Terrorism and Disorder set up in the USA in response to the increased number of hostage incidents being committed by both international and domestic terrorists. He debriefed numerous former hostages and wrote a memo for the FBI defining Stockholm Syndrome from the perspective of those involved in negotiation and rescue.

“In this type of situation there will be bonding, and the bonding can go both ways,” Ochberg tells me. “As I have boiled it down, it’s very important to realise that when we’re a hostage, we’re infantilised. We can’t eat, we can’t defecate, we can’t do biological necessities without permission. So, we’re not just like an infant metaphorically, we’re like an infant physiologically.”

From his interviews, Ochberg found that subsequent “little gifts of life” led to growing attachment akin to mother-child bonding. An Italian magistrate kidnapped by the Red Brigades came to view one of his captors in the same way he viewed his teenage son. The editor of a Dutch newspaper kidnapped by Moluccan nationalists described the warmth he felt towards his captors who chose not to shoot him.

“He was pretty sure he was going to be killed,” says Ochberg. “He told me ‘they gave us blankets, they gave us cigarettes, they were human’ but he was told he was the next to be executed, but then that didn’t happen. He had a very strong Stockholm Syndrome bond.”

Whereas Bejerot dismissed Stockholm Syndrome as an irrational response, Ochberg views it as more nuanced. “It can be both, not necessarily at the same time,” he says. “I’ve talked to people who said: ‘I knew damn well what I was doing’ and others who really appreciated me telling them that although they did something they considered shameful, it was a survival reflex, and it was appropriate.”

Furthermore, Ochberg’s definition crucially requires a psychological change on the part of both parties. “Those who are holding, imprisoning, torturing, certainly abusing their surrogate children are also having a connection,” he says. Thus, together the hostages and the hostage takers develop a mutual distrust for the authorities. Consequently, Ochberg, seemingly counterintuitively, advised hostage negotiators to cultivate these bonds as, put simply, it would make it harder for the captors to kill their hostages.

Yet, in the decades since the Norrmalmstorg incident, Stockholm Syndrome has been the subject of increased criticism. Enmark, now a psychologist herself, has become increasingly vocal in her criticisms of the pathology assigned to her, arguing that it’s men who get to decide what is considered to be “rational” behaviour.

Jess Hill, the author of See What You Made Me Do: Power Control and Domestic Abuse, dismisses Stockholm Syndrome, which has often been attributed to women who stay in abusive relationships, as “a dubious pathology with no diagnostic criteria” and that it “is riddled with misogyny and founded on a lie”.

The majority of hostage situations don’t end with the captives bonding with their captors, however the media coverage of those that do exaggerates public perception. In the last five years alone, the events at the bank have been dramatised twice, in the film The Captor and in the Netflix series Clark.

A study conducted by academics at London’s University College Medical School determined that there was sparse literature on the syndrome, most being produced by the media. Furthermore, they concluded, over time the definition of Stockholm Syndrome had broadened, blurring the original term. Indeed, as critics point out, despite being one of the most widely known psychological terms, there is no formal diagnosis for Stockholm Syndrome.

Whether it is real or a media myth, an unconscious reaction or a conscious survival strategy, it is clear that the bond that developed in the oppressive confines of the Kreditbanken vault went a long way to ensuring Olsson’s captors did not become his victims. “It was the hostages’ fault,” he said. “They made it hard to kill.”