The Zisa castle sits in the west of Palermo, its distinctive Islamic design of muqarnas and ogival arches a reminder of Palermo’s buried histories and the ArabNorman court that flourished here in the 12th century with its productive exchange between Arab, Norman, Latin, and Byzantine Greek cultures. It is but one of many remaining vestiges of this interconnected past found around the city, from the Arabic inscriptions on street signs to the distinctive hybrid architecture of its most precious buildings.

In the shadow of “La Zisa” lies the cantieri culturali, a former furniture manufacturing centre saved from destruction by the city’s progressive, anti-mafia mayor Leoluca Orlando in 1995 and now home to exchanges between various experimental art spaces, theatre groups and the city’s cultural intelligentsia. Here, the latest collaborative project between the Comune di Palermo and the Turin-based contemporary art foundation Fondazione Merz launched in late October and will see the arts group take up a three-year stewardship of ZACentrale, the largest pavilion in the cantieri.

Birds are singing by the Goethe Institut situated just behind ZAC: a white hangar where, above the door, the finishing touches are being made to a neon installation by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar.

The ladder pulls back to reveal a phrase lit up in red above the entrance: Il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono I mostri. (The old world is dying. The new one is slow to appear. And in this half-light monsters are born.)

It’s a quote from the work of Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, whose archive is housed a few metres away, and marks the entrance to the Fondazione Merz’s inaugural exhibition L’altro, lo stesso (The Other, The Same), curated by Beatrice Merz and Agata Polizzi, and whose title is a nod towards a series of sonnets published by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges.

The Merz name is synonymous with the Italian arte povera movement, a conceptual branch of modern Italian art that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, of which Mario and Marisa Merz were pivotal figures alongside artists Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Jannis Kounellis and Michelangelo Pistoletto (Marisa Merz being the only woman who was associated with the group).

The movement self-consciously rejected consumerism and commercialism as well as shunning the use of traditional art materials such as oil paint on canvas, in favour of recycled materials, ranging from the organic to the industrial. It flourished principally among the anti-fascist urban cultural networks in Turin, Genoa, Milan and Rome.

In many ways, this prevailing ethos underpins what have now become urgent preoccupations with sustainability in our contemporary moment.

“In a way, Mario and Marisa are the starting points for this show,” explains their daughter Beatrice Merz, president of the foundation as well as co-curator of the exhibition, which brings together works by her late parents alongside artists Emily Jacir, Lida Abdul, Sicilian video artist Rosa Barba, Joan Jonas and Lawrence Weiner.

Works by Marisa Merz (many of which have never previously been exhibited) sing with a sense of magical realism in the industrial space.

Small heads, fashioned from unfired clay, sit next to experimental drawings of female faces with dreamy eyes made of aquatic, zoomorphic forms – something between human and animal.

Marisa Merz became known for her pioneering vision of the domestic environment in works such as Living Sculpture (1966), fashioned from stapled strips of commercially available aluminium foil (not on show), and is only recently being accorded appropriate recognition as an artist. Her work has previously been overshadowed by her more famous husband.

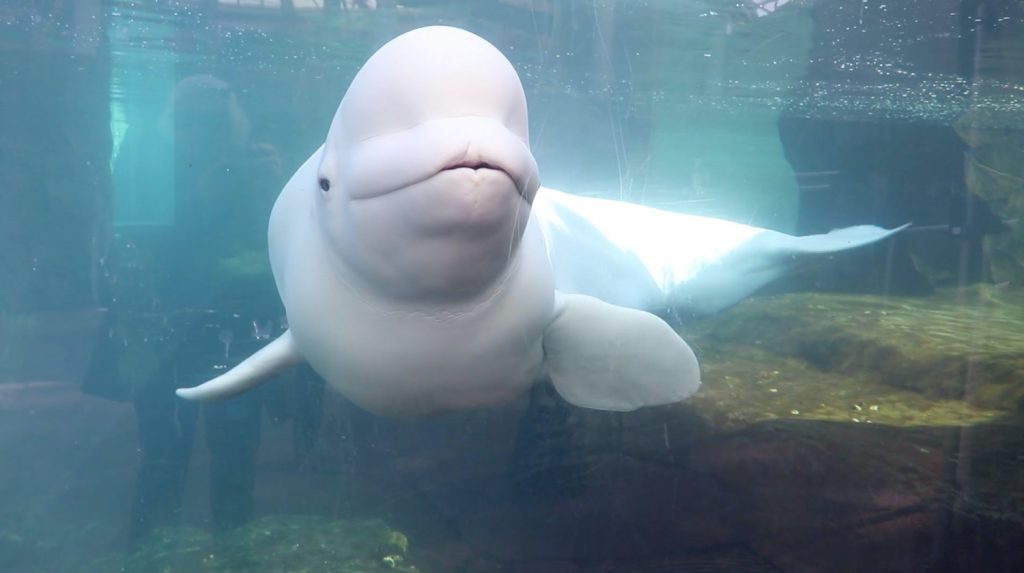

Certainly, sustainability and growth as an early preoccupation of the arte povera movement is a palpable theme in the exhibition. American artist Joan Jonas’s video Moving Off the Land II is a kaleidoscopic ecological collage that meditates on the various confluences between human and animal life in the sea, and our planetary futures.

This finds an echo in the aqueous background lilt of Lawrence Weiner’s untitled video, which, positioned at ground level with four other television sets showing video art, feels like waves crashing over our feet.

This in turn strikes a sympathetic chord with the “sonic writing” of the sound installation by artist duo Graeme Thomson and Silvia Maglioni that accompanies the pedestrian approaching the building from the street, along one of the pavilion’s flanks that is inspired by networks of lichen in the ancient forests of La Gomera in the Canary Islands.

But nature’s unpredictability is also emphasised in Rosa Barba’s film The Empirical Effect, which shows a bellicose Vesuvius and some of the survivors of its most recent eruption in 1944.

The gargantuan space is dominated by a work by Mario Merz, consisting of a spiralling metal frame on which sit blocks of stone piled with a cornucopia of real fruits and vegetables, like an enormous sculptural “still-life” banquet.

For Merz, the forms were inspired by the physical geometry of the mathematical Fibonacci sequence, a form that underpins the material growth of all matter, from sunflowers to the shape of galaxies in space.

As such, it invites the viewer to perceive a world beyond the superficial and familiar frameworks to which we have become accustomed, and offers an enquiry into the unseen networks that sustain planetary activity and growth.

Importantly, Beatrice Merz emphasises, this work will “nourish” the community in a literal sense. “As the organic produce matures and ripens, it will be sent to a local association that teaches young people how to cook, before being replaced with new food in the gallery,” she says.

“Another concept that always informed our work is the idea of nomadism, whether [in the art made] by Mario and Marisa in their own time, or our foundation now.

“It’s the idea of not staying put in one place, of not wanting to have a museum that is a fixed or closed concept. The Fondazione Merz museum in Turin also embraces this sense of not wanting to be limited in one place.”

Between 1968 and his death in 2003, Mario Merz became known for his various “igloo” constructions, inspired by the typical shelters for nomadic wanderers, in works that became a riff on ideas of home, dwelling and identity, themes that find subtle interconnections in this sensitive and nuanced show.

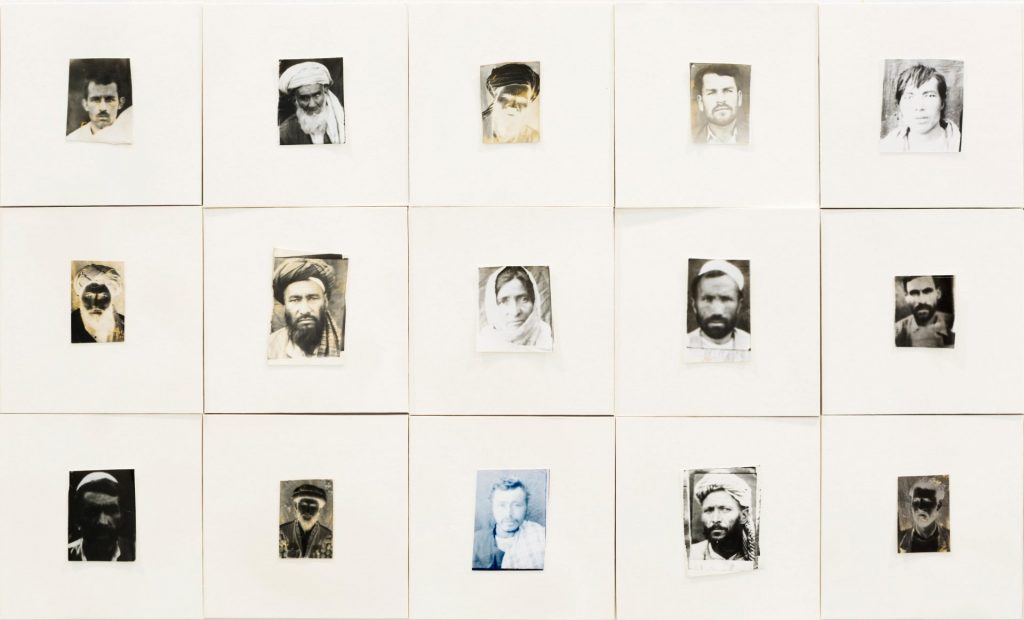

Spanning one of the long walls are the 480 passport-style black and white photos of video and installation artist Lida Abdul’s Time, Love and the Workings of Anti-Love. Faces of anonymous men, women and children, displaced and traumatised by decades of conflict in Afghanistan, stare out from the white wall, in a silent procession.

Elsewhere Palestinian artist Emily Jacir’s looped film Le maglie del pomeriggio, Roma 29 Marzo 2020 offers a different vision of the home as a space of incarceration and anxiety.

Each day during the March 2020 lockdown she produced a photographic diary of extending her washing line into the space above the empty streets, the creaking of its winch morbidly acute in the uncharacteristic silence of the city.

An openness to change and mutation is reflected in various subtle ways as points of dialogue between the works on show, something that intentionally reflects the porosity of Sicily as a geographical and cultural crossroads between North Africa, Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, and the ethos with which Palermo has undergone a cultural and social transformation in recent years.

“We’ve gone to great lengths to promote a sense of the contemporary that also has a memory of its past,” says mayor Leoluca Orlando.

In 2019, the city was host to the 12th edition of the Manifesta contemporary art biennial, which aims to mobilise cultural exchanges as a platform for more profound social change.

Aside from his belief in the regeneration afforded by sustained municipal engagement and support for the arts, Orlando has been credited with helping Palermo recover from the bloodied grip of the mafia, and forging a culture of integration and respect for the city’s migrant community. It’s an approach that is reflected in the motto of Palermo’s city charter: “From the migration as suffering to mobility as an inalienable human right.”

Sicily and islands such as Lampedusa have been at the coal face of the EU migrant crisis, with 13,000 people arriving in 2021 (three times the number in 2020). But Palermo has offered progressive models for integration. Since 2013, 21 elected non-Italian representatives sit on a municipal Cultures Council, representing migrant voices (the current president is Kobena Ouattara Ibrahima from the Ivory Coast, and vice-president Thiyagarajah Ramani is from Sri Lanka). Orlando has changed the conversation from one of ghettoisation and paranoia to one of humanity that appeals to outsiders looking in from fractured, separatist and populist times.

“Palermo is Istanbul, Tripoli, Barcelona, Marseille. The Mediterranean is not a sea that divides us, but a liquid continent that joins us,” he says.