Back in 1983, the US magazine Video Games Player was launching its Golden Joystick Awards. The world of gaming was in its infancy back then, but even so, the magazine made a daring and far-sighted statement, telling readers: “Video games are as much an art form as any field of entertainment.”

It was a bold statement back then, but one that now looks increasingly accurate. In terms of both growth and reach the gaming industry is now bigger than Hollywood. In the UK alone, the video games market is worth £7.16bn. The Grand Theft Auto series of games is one of the most lucrative media products ever made, having sold a total of 170m units with revenues of over $10bn. The game’s publisher, Rockstar Games, was co-founded by brothers Dan and Sam Houser, both from London – and yet for some reason our politicians don’t have much time for the gaming industry, preferring instead to concentrate on fishing, which is worth approximately £0.4bn per year.

By 2026, global gaming industry revenues are expected to exceed $320bn. The sector’s enormous size is not lost on the European Parliament’s Culture Committee, which recently published data showing that, in 2020, the sector provided more than 98,000 jobs – a 7.6% increase from 2019 – in mainly small and medium-sized enterprises. Last year, Europe’s video games market had revenues of €23.3bn, while the player base increased by 6%. That growth was driven – remarkably – by women and 45–65-year-olds.

Computer games are a huge industry – and I would agree with the editors of Video Games Player that they are also a form of art. Modern games, with blockbuster budgets, detailed plotlines and the use of actors, are every bit as valid a form of storytelling as films, TV or visual art, with the vital addition of allowing the player to guide the action. The record for most Game of the Year awards is held by 2020’s The Last of Us Part II, which was praised for its depictions of empathy, grief and anger, complex emotions strongly suggestive of artistic insight. And even away from the highbrow, almost arthouse, games, some titles have had huge aesthetic impact. Have the instantly recognisable style and palette of the Super Mario Brothers games been any less influential than, say, the works of Roy Lichtenstein?

And yet videogames are not taken seriously as a form. So what might convert the unconvinced?

How about a major exhibition at the Imperial War Museums (IWM) on the portrayal of war in video games? Visit the London museum and that’s what you will see: the UK’s, possibly the world’s, first exhibition on how war is represented in the virtual world of computer games. Made up of immersive installations and previously undisplayed objects along with contributions from industry experts, War Games ranges from the early days of cassette-loaded 2D animation to today’s photo-realistic blockbusters.

Ian Kikuchi is a historian and the museum’s senior curator for the Second World War and Mid-20th Century. As we walked around the museum, he described the origins of the exhibition. “It occurred to me that, just as war films are a big part of the way pop culture reflects and represents war and conflict, so too are video games,” he said.

“For me that’s an obvious observation, because I’ve been playing video games since I was five years old. I’ve been a curator for 15 years but I’ve been a gamer for about 30.”

In Kikuchi’s view, each generation has its defining technology, which is inevitably used to tell stories about war. “So in the Crimean War, photography was the new medium. By the time of the First World War, film and cinema. Radio comes along in the ’20s and you get frontline radio broadcasts from the Second World War, then TV and the Cold War go hand in hand. So by the 1970s, once computers start getting into people’s homes and arcades, it’s natural to see video games start to talk about war also.”

But why are video games regarded as subcultural? “That seems to be a hangover, a really long hangover from the late ‘80s,” says Kikuchi. “But it does seem that as an art form, as a cultural medium, as a creative medium, video games are beginning to come into their own as a recognised form of cultural expression.”

The exhibition is made up of 10 spaces, or levels, as they are called, fittingly. The first emphasises the deep relationship between games and conflict. Chess, the most ancient of games, includes pieces that represent both knights and castles. A set on display was carved by a British prisoner of the Japanese in WWII, a labour that speaks to the psychological need for play, even in the worst of times. Two snakes-and-ladders games, one from the First World War and one from the Second, show that games can share the same mechanics and rules and yet mean different things. In one game, the players rise through the Army ranks. In the other, the aim was to destroy a German factory by bombing. Both games were intended as propaganda for children.

Deeper into the exhibition, a nine-channel surround-sound system demonstrates the importance of audio effects in games. The soundscapes switch between an island, a warehouse, a haunted house, the sea and a jungle – the effect is extremely powerful. A video explains how the visual worlds are created, such as that of a frankly horrifying and highly realistic terrorist scenario in Piccadilly Circus in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. The level of detail is astonishing. Rarely has the horror of such incidents been conveyed so viscerally.

The immediacy of computer games perhaps reached its peak in one of the most popular, and occasionally controversial, genres of computer game, known as the “shooter”. The first of these was 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D, a game set inside a World War II German prison. It was one of the first successful “first-person shooters”, in which the game is shown from the point of view of the protagonist.

“It’s the archetypal escape from the Nazi castle story,” says Kikuchi. “The Second World War has always seemed like a safe place to tell adventure stories. Somehow you don’t tell adventure stories in the First World War, really. The Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the War in Iraq – those are always seen to be remembered or represented very differently.”

Although Wolfenstein 3D is regarded as the grandfather of first-person shooters, its antecedents go back much further. One curiosity on show in the exhibition is the early 20th-century phenomenon of “cinematic shooting galleries”. The first of these appeared in 1912, and involved players firing bullets at still, and sometimes moving, images projected on a cinema screen. There were apparently several of these galleries in London. A direct hit would either cause a light to switch on, or pause the film, allowing the shooter to check his aim.

It was all a bit of fun – but the modern equivalent goes much deeper. The forthcoming game Six Days in Fallujah follows a squad of US Marines as they battle their way through the Iraqi city. The game was originally slated for release in 2010, but was cancelled amid controversy and objections to depicting something which was then so painfully fresh in the memory.

The exhibition shows video footage of the photo-realistic game, and displayed alongside is an electronic keyboard which, Kikuchi explains, was “the prized possession of a gentleman living in Mosul who fled his home in 2014 as the city was threatened by ISIS militants”.

“And he knew that he couldn’t take it with him, so he abandoned it. He eventually resolved to return home and found it had been smashed up by the people who had occupied his home. We find soldiers and war fighting very compelling but the stories of civilians get told perhaps less often.”

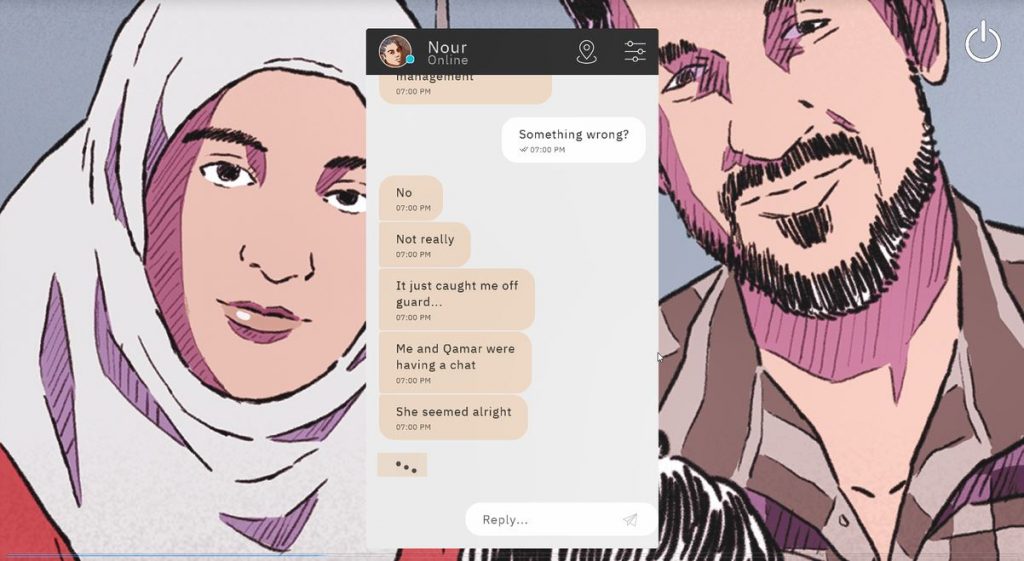

One which does focus squarely on the plight of civilians in war is Bury Me, My Love. In fact, this 2019 game may do more than anything else in the exhibition to change the unconverted’s mind about the story-telling power of the medium. It is a text-based game, a modern-day equivalent of the eight-bit text adventures of the 1980s, and it tells the story of Nour, a Syrian migrant trying to find her way to Europe. The player is her husband Majd, who remains behind in Syria and communicates with her through a messaging app, advising her as best he can, to help her reach her destination.

The game plays on your phone, and somewhat unnervingly, it plays out in real time, meaning that a player might put the game down at bedtime and discover that they have had a message overnight. “You communicate with your wife through text messages and emojis,” explains Kikuchi, “and you can give advice and suggestions about how she might make her journey, but you can never actually control what she does”.

The game has around 30 potential endings, including safety and security, refugee status in Europe, ending up stuck in a refugee camp, or even dying somewhere along the way.

When Kikuchi played the game for the first time, his wife-character died of hypothermia after a river crossing. It had an unexpectedly strong effect on him. “I sat with the game for a while, thinking ‘Should I restart it and have another go and see if I can get a better ending?’ But I thought, actually, I won’t do that, because I played the game seriously and I tried to make the best choices that I could, and that was how it ended. And I felt like the game was telling me something about the reality of that journey.”

The great American film critic Roger Ebert famously described cinema as “a machine that generates empathy”. Download Bury Me, My Love on to your phone and that is literally what you have in your hands.

The military is increasingly interested in games and gamers. There is a US army recruitment poster from 2019: “Binge gamers: Your Army needs you and your drive”. Also on display is an Xbox controller used to operate the cameras on a drone which circled over Camp Bastion in Afghanistan. Xbox controllers are cheap, they’re readily available and they’re familiar to soldiers.

The formal exhibition ends with a retro game zone, a selection of war-themed games which will delight both curious youngsters and those of us who were there the first time around. Even some of these were not without controversy at the time. 1992’s Desert Strike was considered in bad taste for being released so close to the first Gulf War. Cannon Fodder, from 1993, with its poppy iconography, was attacked in the British tabloids, although now its intelligent anti-war message makes it more redolent of Blackadder Goes Forth.

War Games was delayed by the pandemic. The museum had hoped to open it last year, but it has been well worth the wait. Fascinating, cleverly curated, often even moving and – as you’d expect from the medium – spectacularly designed, if the very fact this exhibition even exists doesn’t persuade you that video games are an artform, its execution should.

● War Games: Real Conflicts, Virtual Worlds, Extreme Entertainment runs at IWM London until May 23, 2023