Slogan time is here again. The next few weeks will determine if time is finally up for the party that in 2015 promised “Strong Leadership, a Clear Economic Plan and a Brighter, More Secure Future” and then delivered us Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak.

Since then the Conservatives have followed up with “Strong and Stable” (2017), “Unleash Britain’s Potential” and of course “Get Brexit Done” (both 2019), none of which look particularly clever or accurate now. Rishi Sunak’s “Stop the Boats” hasn’t worked – in fact, as Keir Starmer joked in a recent PMQs, he’s been more effective at stopping the votes.

“Clear Plan, Bold Action, Secure Future” doesn’t look likely to cut it this time; and voters seem to quite like the idea of going “Back to Square One With Labour” – if Square One was the time when they could afford to pay their mortgage or rent, do their shopping and heat their homes.

The polls indicate that the last 14 years have left the country longing for the single word on Starmer’s lectern, a few minutes after Sunak’s rain-sodden election announcement: “Change”.

But does that mean “It’s Time for Real Change”? Probably not, as that was Jeremy Corbyn’s slogan in 2019.

What about “Change We Need” and “Change We Can Believe In”, both of which helped get Barack Obama elected in 2008? The simple “Vote for Change” worked for the Tories in 2010 – and what a difference from their hopeless 2005 slogan, which was, erm, “Vote for Change”.

But hang on, wasn’t Starmer supposed to be the anti-slogan man? The guy who stood before the Labour Party conference in September 2021 and faced down Corbynite hecklers, telling them they had a choice between “shouting slogans or changing lives”?

In doing so, he was both confronting his conference-hall taunters and taking a potshot at Boris Johnson’s repetitive promise, much heard at the time, to “Build Back Better”.

Love or loathe political slogans, we are stuck with them. Starmer’s criticism was a bit rich, as his own Labour leadership bid was propelled by the reassuring promise that, “Another Future is Possible”, which is as trite and obvious as they come.

So here’s a test. Which of the following political slogans are genuine and which were created by me just now, using an online slogan generator?

“Continuity and Change”

“Working for You”

“Transition to Greatness”

“Change We Need”

“Forward Not Back”

“Believe in Better”

Tough, isn’t it? The answers are at the end of this article. But if bullshit is so hard to detect, why do political parties persist in using slogans? Presumably because they work. And they have history.

If “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” can be deemed a political slogan, it probably has no equal, either in terms of succinctness or longevity. Coined by Robespierre in the midst of the French Revolution, it had a slow gestation. But its immortality is secure.

“France is Back, Europe Lives Again”, the 2024 European election slogan of Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s far right National Rally doesn’t really come close.

Sloganeering in US presidential elections dates back to at least the 1840 campaign during which William Henry Harrison, famous for the shortest presidency in US history, declared: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”. Alongside that, “Take Back Control” feels like a model of clarity.

Harrison was referring to his 1811 military victory over the native American Shawnee at Tippecanoe, and thus is a slogan unlikely to reappear in these more progressive times (although, if Donald Trump makes a comeback, who knows?)

Though short-lived, Harrison was successful, setting in train a never-ending search by political advisers for the ideal mix of vague unintelligibility and inspiration that will set their candidate apart from the equally superficial guff being spouted by the opposition.

So what constitutes a successful political slogan? They should sound positive, rather than negative – a tricky task to pull off when your whole raison d’etre is moaning about the status quo, which is why the far right Sweden Democrats’ current European election slogan “My Europe Builds Walls” sounds so weird and sinister.

The three-word structure beloved of Johnson and Dominic Cummings is a good template, but they are not all three-worders. What sets a corker apart from a turkey, and – in today’s era of TikTok, Instagram and Twitter/X – how can you guarantee that it stands out and cuts through the noise of people’s daily lives?

Lucy Chapple, head of client strategy at communications consultancy Stand Agency, says: “It must communicate a clear call to action; a sharply articulated emotion that reaches the target audience. There should be no room for doubt or confusion.”

This means that, whatever you may think of him, Trump’s “Make America Great Again” (MAGA) was a classic of the genre. “It unified, spoke to the disenfranchised and played on fear, nostalgia and hope,” says Chapple. But we mustn’t get too complimentary. Trump nicked it from Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign, simply dropping the initial “Let’s”.

And of the three-worders? Max Atkinson, the political speechwriting analyst, has identified three-part lists as a key weapon in effective communication. They may have been misguided and at worst mendacious, but “Take Back Control” and “Get Brexit Done” were two horribly effective examples.

Politicians can’t do without a good slogan – but a slogan alone won’t get them into power. They need a good campaign too. “Not Flash. Just Gordon”, did nothing to save Gordon Brown in 2010.

“Build Back Better” clearly didn’t hit the rhetorical heights, sounding more like the strapline you’d find on the side of a builder’s van. But vacuity and solipsism are not necessarily the bedfellows of failure. The banal “I Like Ike” won Dwight D Eisenhower (nicknamed Ike) the US presidency in 1952. And he was re-elected in 1956 using: “I Still Like Ike”.

Ironically, before MAGA, the most memorable American presidential slogan of recent times, one that delivered the nation its first black president, was not official at all. “Yes We Can” chanted Obama’s youthful supporters in 2008, although the actual campaign slogan was the aforementioned “Change We Can Believe In”.

Likewise, Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign is remembered for “It’s the Economy, Stupid” but his official slogan was the cleverly formed but actually rather mundane “For People, For a Change”. But sometimes mundane works: “A Chicken for Every Pot” got Herbert Hoover elected in 1928.

Elsewhere, revolutionary Russians were galvanised by Lenin’s “All Power to Soviets: Bread, Peace, Land”, which was brilliant rhetoric but unfortunate timing, preceding three years of civil war. There will be those who think it distasteful to include slogans from regimes responsible for mass slaughter, thus precluding Adolf Hitler’s “Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer”, which certainly had them stupefied in the ranks at Nuremberg.

Across the North Sea, Hitler’s nemesis, Churchill, was working his own propagandistic magic with “Success is Not Final, Failure is Not Fatal” and “We Shall Never Surrender”. There was only likely to be one winner.

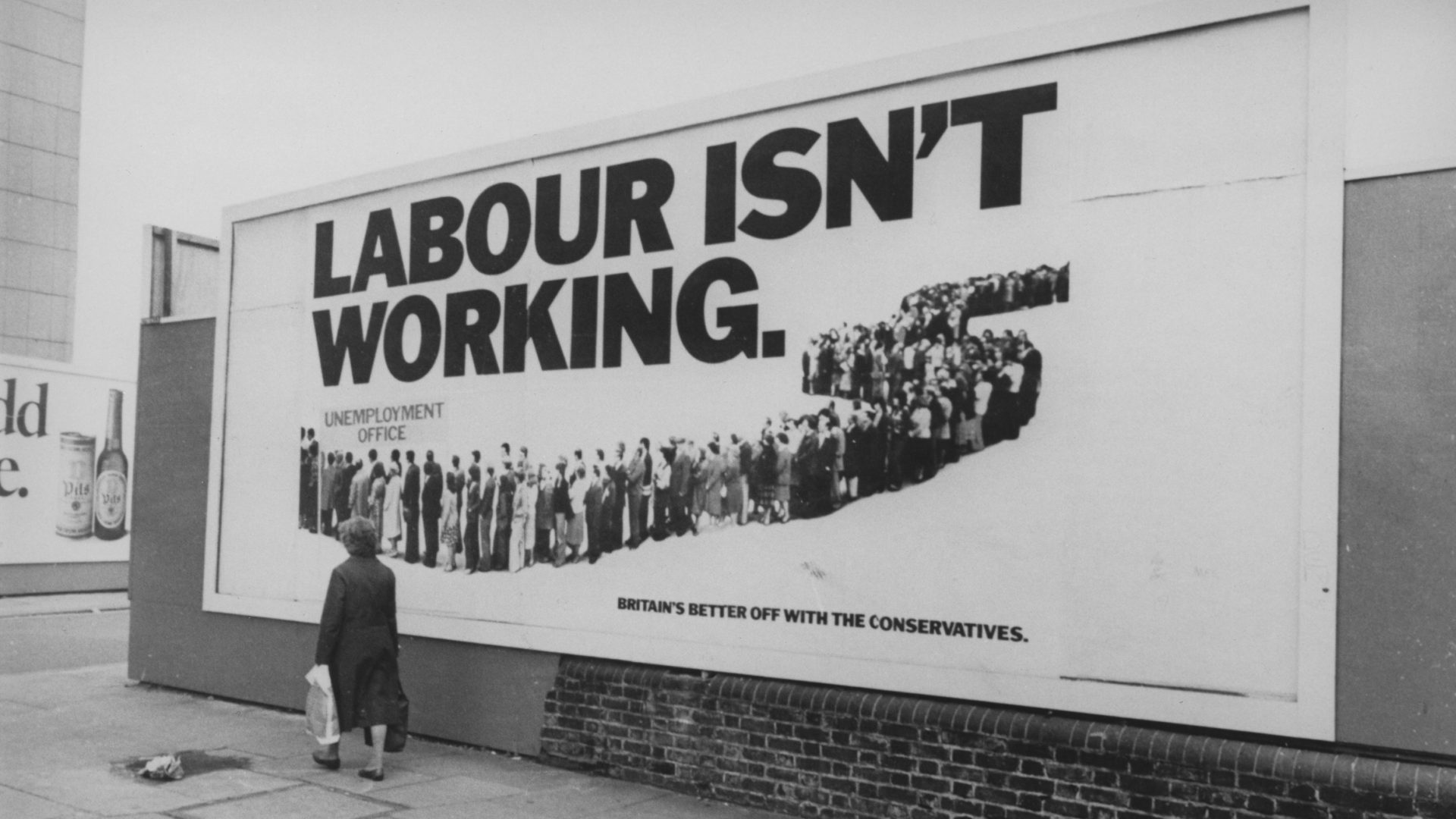

Postwar spin doctors and advertising execs have had more time and resources to hone the message. “Labour Isn’t Working”, plastered on billboards around the country and devised by ad agency Saatchi and Saatchi, was one of the first campaigns to actively court the creativity of the communications industry and it helped to deliver Margaret Thatcher’s first general election victory.

That the line of people depicted on the poster supposedly standing in a dole queue later turned out to be a bunch of actors only drove home the point that it was the message, not the reality, that mattered. “New Labour, New Britain” did much the same for Tony Blair in 1994 when he repositioned his party after years of opposition and won the 1997 general election.

Of course, for every “Yes We Can” there is a “No You Didn’t”. Readers of this newspaper will probably cringe as they recall ex-prime minister Theresa May’s insipid “Red, White and Blue Brexit”. Still, at least it had a certain rose-tinted, if jejune patriotism.

Former Labour leader Ed Miliband’s attempts were apparently designed to induce torpor: “It’s Not Good Enough for Britain”, and “Hardworking Britain Better Off”. The former was obviously written by shadow cabinet ministers contributing a word each, the latter barely literate; apparently totally dismissive of those who don’t or can’t work. It turned out that 98% of Labour members disliked it, which didn’t bode well for the rest of the electorate. But the Tories could do boring just as well: “A Britain Living Within Its Means” sent voters to sleep in 2015.

Yet messages of positivity, successful or otherwise, are not always necessary. In 2016 the Australian Liberal party, part of the ruling coalition, ran with “Stick with the Current Mob for a While”. The electorate did.

Liberals are obviously keen on the esoteric pitch. In the second British general election of 1974, having done well in the first, Jeremy Thorpe’s party encouraged people to give it “One More Heave”, breaking with a tradition that usually encourages voters to turn up, not throw up.

The lesson there is to beware ambiguity and double meaning. A prominent news organisation for which this author once worked was on the verge of signing off: “If it’s News to You, it’s News to Us”. Fortunately, at the last minute somebody said: “Erm, hang on…”

And it’s not great to take on a slogan associated with something or someone unpleasant – a lesson Lithuanian PM Ingrida Šimonytė, learned recently when she scrapped her re-election slogan “Strong President, Strong Country” after learning that it had been used by Vladimir Putin in 2018.

Yet, the ingenuity of ad creatives notwithstanding, the electorate is not always easily hoodwinked by a three-word message of vapid-hope-through-inanity. In 1999, protesters outside the World Trade Organisation in Seattle shouted: “Three-word chant. Three-word chant” at delegates inside. Maybe this indicates voters are becoming more discerning.

So while the political slogan is unlikely to go away, and as “Build Back Better” morphs slowly into “Blame Everyone Else”, it may be that, after July 4, even vague promises of positive change might return to haunt the spin doctors.

Mick O’Hare is a freelance journalist, author and editor

ANSWERS

“Continuity and Change” – REAL

Used by Malcolm Turnbull’s Liberal party in the 2016 Australian general election, although Armando Iannucci’s political satire Veep had earlier used the equally inane spoof slogan “Continuity with Change”. On having it pointed out, Turnbull appeared pleased rather than embarrassed.

“Working for You”– FAKE

“Transition to Greatness” – REAL

Used by the Trump campaign in the 2020 presidential election.

“Change We Need” – FAKE

“Forward Not Back” – REAL

Used by Labour in 2005

“Believe in Better” – NEITHER

It’s actually a Sky TV slogan – but admit it, if you’d heard it uttered by Grant Shapps you wouldn’t have questioned it.