Britain seems to have been an entirely monolingual Celtic-speaking island before the arrival of Latin on these shores.

But when exactly did Latin arrive?

There is good evidence to indicate that at least some members of elite Celtic groups in southern England started to acquire some knowledge of Latin after the penetration of the Roman legions to the English Channel coast – no more than 18 nautical miles from England across the Channel at its closest point – after Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in about 50BC.

Gold coins minted some time between 40BC and 20BC which were discovered in Alton in Hampshire bear the name of the Celtic ruler who issued them, written as Commios, with the Celtic suffix -os. However, coins issued by a ruler who appears to have been his son, and dating to somewhere between 20BC and AD10, give this son’s name as Tincomarus, with the Latin -us ending.

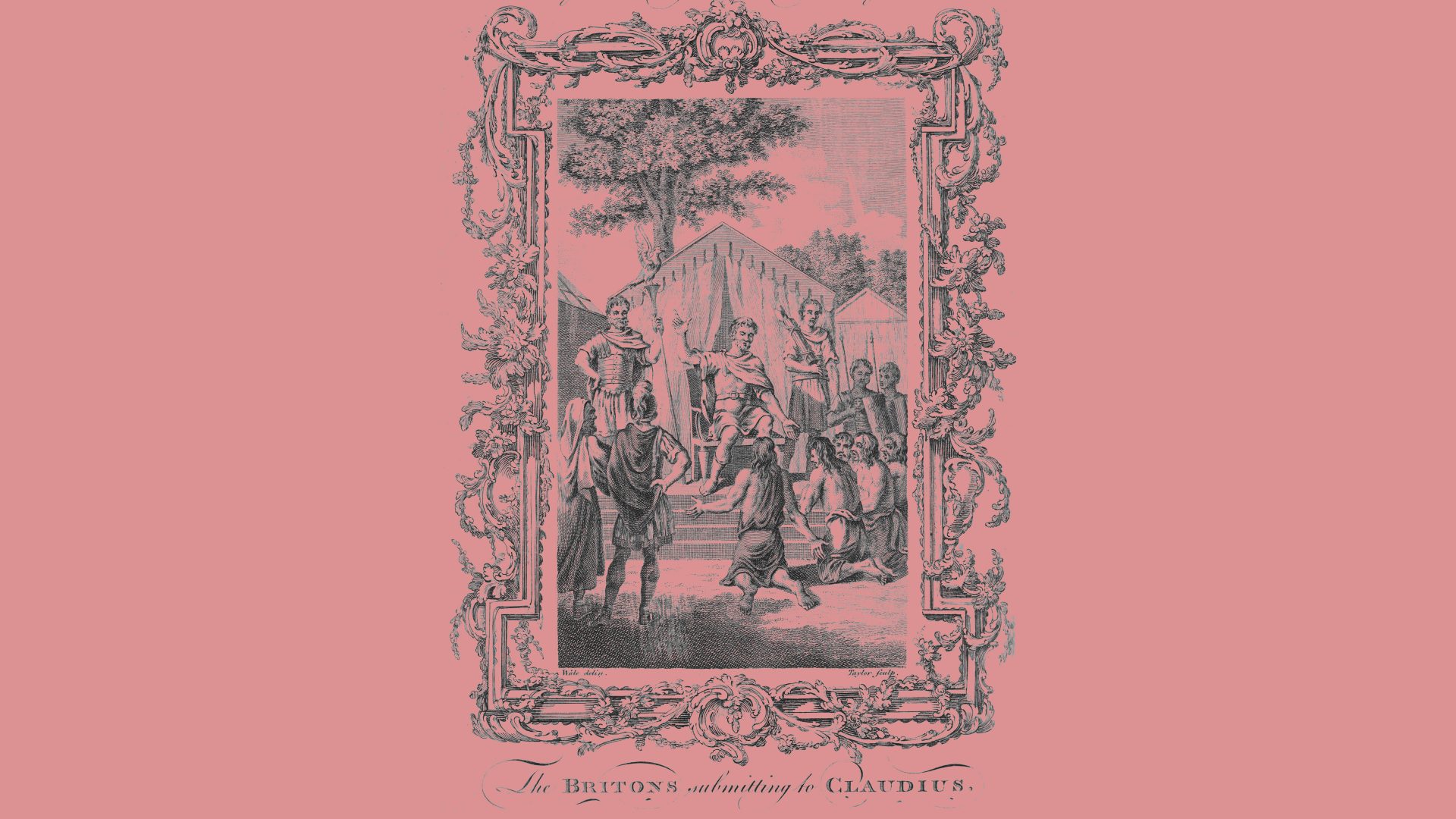

Several other archaeological finds from around the same period also suggest a move towards the use of Latin for ceremonial purposes in this part of England around the beginning of the first century AD, and point to a certain amount of familiarity with the language on the part of Celtic officials in the south-east of England even before the Roman invasion of AD43 during the reign of Emperor Claudius.

His Roman invasion force, led by Aulus Plautius, landed at Richborough near Sandwich in eastern Kent. An army of Celtic Britons, who had been taken by surprise by the invasion, attempted to halt the invaders at a crossing on the River Medway by Rochester, but were defeated.

The Romans then carried on to the Thames, where they were joined by the Emperor Claudius himself. He took charge of a major battle there, which was again won by the Romans, who then marched on to what was probably the most important of the Britons’ towns, Camulodunon (modern-day Colchester). They seized it from the local Celtic king, Caratacus (Brittonic Caradoc), who then withdrew to Wales, where he fought a final and unsuccessful battle against the Romans in AD50, at Caer Caradoc ‘Fort of Caradoc’ (modern Welsh Caer Caradog) in Shropshire.

There were subsequently several anti-Roman rebellions, famously including the large uprising in AD60 led by Boudica, the Queen of the Norfolk-based Iceni, who sacked Roman Colchester, Verulamium (St Albans), and Londinium (London).

The Romans eventually defeated her and her other British allies in AD61 at a battle which is known today as the Battle of Watling Street: we do not know exactly where it took place, except that it occurred somewhere between London and Wroxeter along the line of the Roman Road later called Watling Street – the modern A5 trunk road.

It was not until about AD90 that the Romans managed to subdue the whole of England and Wales. And they were never successful in seizing control of Scotland: in the end, they constructed the defensive line of Hadrian’s Wall across the north of England from the Solway Firth to the Tyne which, from about AD130, marked the northern frontier of Roman-controlled Britain and, indeed, of the Roman empire itself.

The Latin language therefore never had any real living presence in Scotland.

CARATACUS

The original form of the king’s name in his own Brittonic language was probably Karatákos, with the emphasis on the third syllable. This corresponds to Modern Welsh Caradog. The name meant ‘beloved’, and derives from Proto-Celtic karo- ‘love’, which is related to Latin caritas ‘love’ and hence to English charity.