As I walk down the gangplank, a guy in sunglasses dances on the second deck, punching the air in time to ear-splitting techno beats. Then a man in a cassock scurries past, dragging a suitcase. There’s a motley group on this river cruiser: young couples, elderly tourists, students from an agricultural college, pilgrims and the odd monk.

Pyotr Tchaikovsky once stood on this same embankment in St Petersburg. A century and a half later, I am recreating the journey he made down the River Neva to Valaam, a monastery founded in the 14th century as a northern outpost of the Eastern Orthodox Church against pagans. You can only get there by boat – it is on an island in the middle of Lake Ladoga, Europe’s biggest freshwater lake, between St Petersburg and Finland.

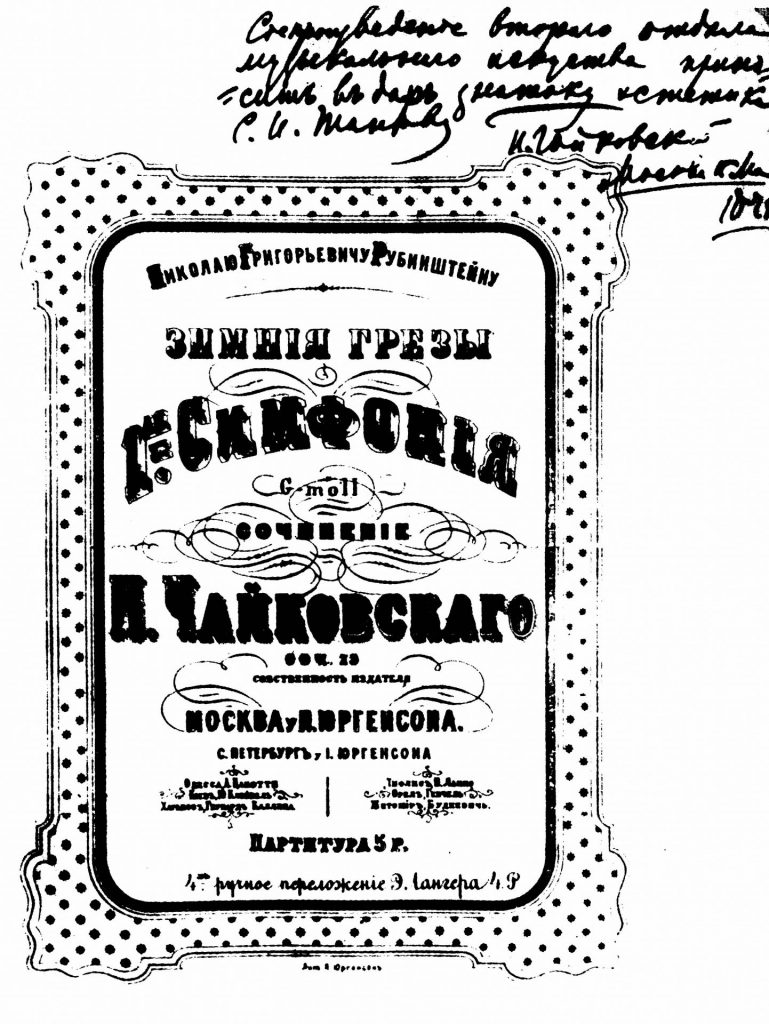

In 1866, Tchaikovsky was in his mid-20s and had just embarked on his first symphony – at the time a musical form virtually unknown in Russia. His boss at the Moscow conservatory, pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, had high hopes for the work and piled on the pressure. But, as Tchaikovsky confessed in a letter to his brother Anatoly, his first full-scale work, Winter Daydreams, was “going sluggishly”. He experienced “dreadful hallucinations” and almost suffered a nervous breakdown as he struggled with writer’s block, chain-smoking into the small hours.

One of the composer’s friends, the poet Aleksey Apukhtin, suggested a trip to Valaam for some fresh air and new ideas. The island was a favourite haunt of writers such as Alexandre Dumas. But Tchaikovsky said he could not spare the time. He came to the river port to wave his friend off and was then lured on board by the promise of delicious jam from the ship’s buffet.

Tchaikovsky was happily drinking tea and spooning the jam into his mouth when suddenly the siren sounded, and the ship sailed from the dock. Like it or not, he was on his way to Valaam because his friend had sneakily bought him a second ticket. But he arrived totally unprepared, with no clean linen or tobacco. At least that’s the story as told by Yevgeny Kuznetsov, a Soviet-era tour guide who spent decades showing day-trippers around Valaam and wrote a best-selling book about it.

On arrival in Bolshaya Nikonovskaya Bay, we disembark and make our way to the Spaso-Preobrazhensky Cathedral for the Sunday Service. I run into Brother Maxim, an English speaker in his early 30s who used to be an import manager for a trading company near the Chinese border. How did he end up in this remote part of north-west Russia and was he from a religious family, I ask? He shrugs. “We don’t know exactly how God knocks on the door of a human heart. My parents only got baptised several years after I joined the church.” He adds that he was also once a drummer in a rock band, but says: “I don’t want you hunting on Google for it. That was all long ago.”

These days Brother Maxim devotes himself to a different kind of music. He takes me to one of the island’s many sketes – isolated settlements of monks around a church – to give me a demonstration. We meet Father David, a statuesque man with olive-green eyes and a mischievous smile who used to be a jazz musician and now runs the monastery choir. He explains that they have a unique form of liturgical singing, based on Byzantine culture, called the Znamenny chant. It is not written with notes but with special signs, called Znamena – Russian for “marks” or “banners”.

All of a sudden, the small church reverberates to the trance-like sound of an Easter chant celebrating the resurrection. Father David sings the melody and Maxim sings the ison – a low note that sets the tone. “We don’t know what Tchaikovsky thought about our chants,” says Father David. “I think to his ear it probably sounded very primitive. He was used to hearing 32 instruments playing all at once in his head! But it was God’s providence that while he was on Valaam he overcame his inability to write.”

Later, I climb to the top of the cathedral’s bell tower with a couple of monks to get a bird’s-eye view of Valaam. It’s a crisp autumn day and there are magnificent vistas across the island and the lake, but they tell me that when Tchaikovsky visited it rained most of the time.

Maybe that is why the Adagio of his First Symphony, which initially gave him so much heartache, is called Land of Gloom, Land of Mist. It begins with muted strings, before a haunting melody on the oboe seems to echo over the Ladoga waters like a hymn.

Despite what Father David says, Tchaikovsky actually appreciated the asceticism of Znamenny chants. A decade after his trip to Valaam, he composed an acapella choral work based on texts from the divine liturgy of St John Chrysostom or St John the Golden tongued, the famously eloquent 4th-century Archbishop of Constantinople. But the liturgy’s premier caused a scandal. One Moscow priest, Amvrosiy, fumed: “We cannot begin to say how the combination of the words ‘liturgy’ and ‘Tchaikovsky’ offend the ear of the Orthodox Christian.”

It’s hard to see how the composer’s restrained settings of biblical texts caused such a row. But even secular music faced opposition from the Church until the mid-17th century. When Tsar Aleksey Nikolayevich, father to Peter the Great, asked foreign musicians to come to Moscow to teach Russians to play western instruments, Orthodox priests ordered the instruments burned and called for the musicians to be whipped.

As dusk falls the day-trippers return to the boat. The skipper plays the slow second movement as cruisers leave the island. I watch as this floating palace of sound and bright light moves further and further across the lake until it is swallowed up in darkness.

Despite allusions to gloom and mists, Winter Daydreams is suffused with optimism, drawing on the landscapes and rich heritage of the Russian North. The silvery flute and shivering strings of the first movement evoke a troika racing across the snow. Tchaikovsky was inspired by melodies

of his childhood and the Fourth Movement draws on a folk song, Shall I Plough the Land, Young One?, which builds into an exultant dance for bassoons and violas, then the entire orchestra. The accented offbeats sound exotic and defiantly Slavic.

Back in St Petersburg, I meet Alexander Kantorov, conductor of the State Symphony Orchestra Klassika, who regards Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony as a masterpiece. “He was only 26 years old when he wrote it, but people of all ages can find something in it that resonates,” he says.

Some critics and former tutors did not agree. They wanted Tchaikovsky to follow the symphonic model established by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. In short, more structured and German, less melodic and Russian. But audiences loved it at the premiere in 1868 and it remained one of Tchaikovsky’s favourite works. Later he called it “a sin of my sweet youth”.

As for Apukhtin, his early promise faded and he and Tchaikovsky drifted

apart. Years later, he wrote a poem looking back on their youth, and the small role he played in establishing the legend of Russia’s most famous composer on the island of Valaam. He wrote: “I’m proud to have guessed that spark of divinity in you/ Back then barely glimmering/ And now burning with such a powerful light.”

Tchaikovsky’s Island of Inspiration was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 – the podcast is available here