In the opening pages of Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll’s Alice

wonders to her kitten whether “the snow loves the trees and fields, that it kisses them so gently? And then it covers them up snug, you know, with a

white quilt; and perhaps it says, ‘Go to sleep, darlings, till the summer comes

again’”.

Somehow the kitten puts up with several paragraphs of this simpering tosh, confirming it as a fictional feline: any real cat worth its whiskers would have slunk off at the first hint of wishy-washy meteorological anthropomorphism.

Recent winters have done little to inspire such fey literary paeans to nature’s benevolence. Rain and an occasional humdinger of a storm stripping the russet beauty of autumn from the trees and sending torrents of flood water through rural new-builds have been about the extent of it. If there is an upside to these relatively mild winters, apart from heading off girls waxing sickening about snowdrifts, the seasonal darkness encourages agreeable periods of introspection, reflection – and reading.

The end of the year provides an ideal opportunity to scan the shelves and look back over another literary turn around the sun. This was the first year since 2019 not dominated entirely by Covid, meaning book festivals returned to in-person events even if some notable fixtures on the calendar reported disappointing ticket sales. TikTok, meanwhile, defied expectation by becoming arguably the most influential platform for online literary discussion.

In August there was the appalling assault on Salman Rushdie that cost him the sight in one eye, among other injuries, while the literary world is all the poorer for the deaths of Barbara Ehrenreich, Dervla Murphy, Jack Higgins, Raymond Briggs, Marcus Sedgwick, Carmen Callil and Hilary Mantel to name just a few.

And there were books, of course. Plenty of them. Was this a good year for new books? Every year is a good year for new books. Every year has its smash hits and its stinkers, its word-of-mouth bestsellers and high-profile flops. Every year someone will find a book that resounds, one they will read

and re-read, give as a gift and rave about to friends. A book that in years to come they will pull from the shelf, flick through pages tattered and swollen from years of handling, think about the person they were when they first read it and the person they have become and sit down with it again, beginning with the first familiar line. Every year produces a book that means this much to someone; every year is a good year for books.

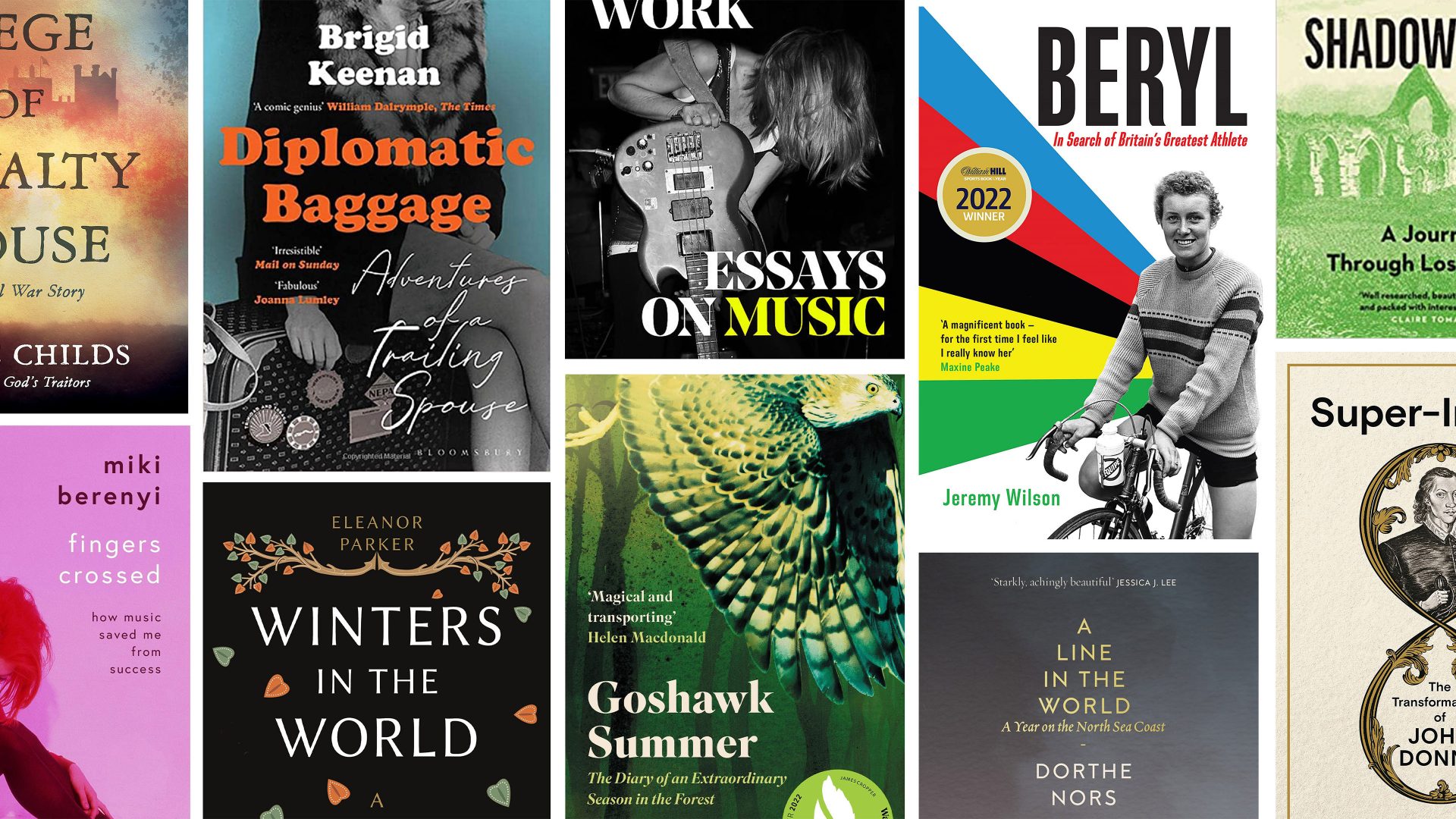

In the world of narrative non-fiction, the Baillie Gifford prize – in effect the non-fiction Booker – was won by Katherine Rundell for her excellent Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (Faber & Faber, £16.99). Best known as a writer of books for children, Rundell is a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, whose examination of Donne’s life, work and his place in the world was a worthy winner of the prize. Beautifully written and hugely enlightening about one of English literature’s most contrary – and in recent times overlooked – figures, it’s a book that should endure as the definitive work on one of our most important poets.

The Wainwright prize for Nature Writing, a genre that has kept its place as the most popular in non-fiction, was scooped by James Aldred for Goshawk Summer: The Diary of an Extraordinary Season in the Forest (Elliott & Thompson, £9.99), his immersive account of a pandemic summer spent filming goshawks in the New Forest at a time when other humans were almost entirely absent and the birds and other wildlife could reclaim the woodland as theirs.

Jeremy Wilson’s Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete (Pursuit Books, £20), a long overdue and remarkable biography of a remarkable cyclist, won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year, while the Stanford Dolman Travel award for the best travel book of the year went to The Amur River: Between Russia and China (Vintage, £10.99) by the great Colin Thubron, a typically erudite account of his journey along a river few have heard of let alone visited, but which is the 10th-longest in the world.

Away from the gongs, there were two other standout titles from this year’s crop of travelogues. Recent years have seen a curious fascination with geographical loss and decay and in Shadowlands: A Journey Through Lost Britain (Faber, £20) the historian Matthew Green, previously a London

specialist, explores our disappeared places, from villages abandoned during the Black Death to the Atlantic archipelago of St Kilda, whose last residents begged to be evacuated during the 1930s. A book of ghosts that resonates in a curious way, as if echoing the political decay we have experienced over the last decade or so.

Across the North Sea, I was utterly beguiled by Dorthe Nors’ A Line in the

World: A Year on the North Sea Coast (Pushkin, £16.99). Like Shadowlands,

this is travel writing about places that wouldn’t necessarily be on anyone’s

bucket list, but which are all the more fascinating as a result. Nors’ evocations of Denmark’s Jutland coast are erudite and philosophical, an outstanding mix of memoir and travel inhabited by absences that is a perfect

complement to Green’s book across the North Sea.

Returning to winter, one book I particularly enjoyed was Eleanor Parker’s Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year (Reaktion Books, £14.99). Parker, a lecturer in medieval history at Oxford University, sheds light on significant dates in the medieval calendar and the festivals and celebrations that went with them. Her winter here is the antithesis of Alice cooing at her cat, a season of long nights, dark forests, rock-hard ground and bone-chilling cold as expressed by accounts left between the fifth and 11th centuries. This beautifully written account transports us through each season in a deeply sensual manner, from freezing ice to warm, spongy loam in a year whose rituals are still thrumming below our own seasonal journeys.

Further forward in time is Jessie Childs’ The Siege of Loyalty House: A Civil War Story (Bodley Head, £25), the kind of history book that reads like a novel and is all the better for it. The English civil war is easily passed over as just another dramatic historical stepping stone among many others, but it remains the greatest political and social upheaval to take place on English soil, certainly since the Norman invasion. Childs skilfully weaves the wider themes and narratives of the conflict into her thrilling account of the besieged royalist stronghold of Basing House in Hampshire between 1643 and 1645 through history writing of the highest quality, with a fabulous cast of characters.

Good writing about popular music is too often hard to find. For too long it was the preserve of male writers overwriting their sneery, world-weary cynicism, but recent years have seen the emergence of some candid and intelligent takes on music, particularly from female writers. This year Miki

Berenyi’s Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me from Success (Nine Eight

Books, £22) was the standout memoir, an honest account of her life and years fronting Lush that confronts her own mistakes as well as documenting the inherent misogyny of the music business.

Women’s experiences in pop and rock are also well-documented in This Woman’s Work: Essays on Music (White Rabbit, £20), a collection compiled by the Irish writer Sinéad Gleeson and Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth. A range of

women from Anne Enright to Juliana Huxtable chart the female experience of and relationship with music in a hugely important book destined to become a landmark in music criticism. Enright’s essay on Laurie Anderson stands out even among contributions of consistently high quality.

My pick as non-fiction book of the year is a bit of a cheat as it was first published in 2005 and reissued in an updated edition during the summer.

Brigid Keenan was a pioneering female journalist, a bright young thing of the 1960s who became fashion correspondent and women’s editor at the Observer and Sunday Times before marrying a European Union diplomat and embarking on more than three decades of travelling the world to wherever Brussels required them to be.

In Diplomatic Baggage: Adventures of a Trailing Spouse (Bloomsbury, £9.99), Keenan writes brilliantly, movingly and hilariously of her adventures from

India to Syria, Trinidad to Kazakhstan, charting the parties, receptions and

frequent bouts of loneliness and homesickness that descend upon the dependents of diplomats as well as bringing a host of global locations vividly to life.

Harking back to the tradition of adventurous 19th-century female travel writers, Keenan’s persistent self-deprecation can’t disguise a sharp intellect, rare gift for observation, personal warmth and ability to craft a perfectly-timed zinger.

When the book was first published questions were asked in the House of

Commons about how the UK government could have allowed such a title to appear, at which the Foreign Office had to concede that, being married to an EU ambassador, Keenan wasn’t one of theirs. Thank goodness for that, and thank goodness for this thoroughly enjoyable memoir that also tips its hat to the EU’s work way beyond the borders of Europe.

A decent non-fiction haul, 2022; but as we have established, every year is a good year for books.

Next week: the year’s best fiction.