A sense of alarm has been building in the minds of Sweden’s Kurdish population. One of the world’s largest minorities without a state, around 100,000 Kurds have found refuge in a country renowned for its tolerance. But after the shock electoral success of the far-right anti-immigration Sweden Democrats, they began to feel exposed and vulnerable.

Sweden’s Kurdish community suddenly found themselves at the centre of a diplomatic row over Stockholm’s application to join Nato, one that intensified in late 2022 when a right-wing coalition government was formed by Ulf Kristersson, leader of the Moderate party. The Sweden Democrats, an extreme right wing party, with origins in the country’s post-war neo-nazi movement, forms a part of Kristersson’s government. This is a concern for any minority that is trying to make a life in Sweden, as well as for feminists fearful for women’s rights. It was also a profound and alarming shift in political character for a nation that is often seen as a European, social democratic success story. Those days, it seems, may now be over.

Mixed in with all this was Sweden’s long-running application to join Nato, an ambition that was being held up by President Erdogan of Turkey. Erdogan was unhappy at Sweden’s willingness to admit Kurdish refugees and immigrants, some of whom, Erdogan alleged, were involved in Kurdish nationalist and anti-Turkish activity, verging on terrorism. But that objection has now been lifted, Erdogan saying he was happy for Sweden to join Nato – but he wants EU membership in return.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been especially harsh on his country’s Kurdish minority — and when Ergodan called Sweden a “nest of terrorists” last year, he was referring to Sweden’s Kurds. The presence of so many dissident Kurds in Sweden, including some who are campaigning for their own homeland, infuriates the authoritarian Turkish leader, who leads a country that has struggled with Kurdish insurgents in its southeast. He used Sweden’s Kurdish minority as justification for blocking the country’s bid for Nato membership.

Erdogan was trying to pressurise Stockholm into withdrawing support and aid for the separatist guerrillas of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), their affiliates in Syria and their cheerleaders in Sweden. He also presented Sweden with a list of dozens of mostly Kurdish people for extradition and demanded that Stockholm should adopt a wider definition of terrorism. He also insisted that western arms sales to Turkey should resume.

Sweden’s former prime minister, Magdalena Andersson, eventually agreed a deal last June to accommodate Erdogan’s demands, on paper at least, but the Stockholm government then dragged its feet.

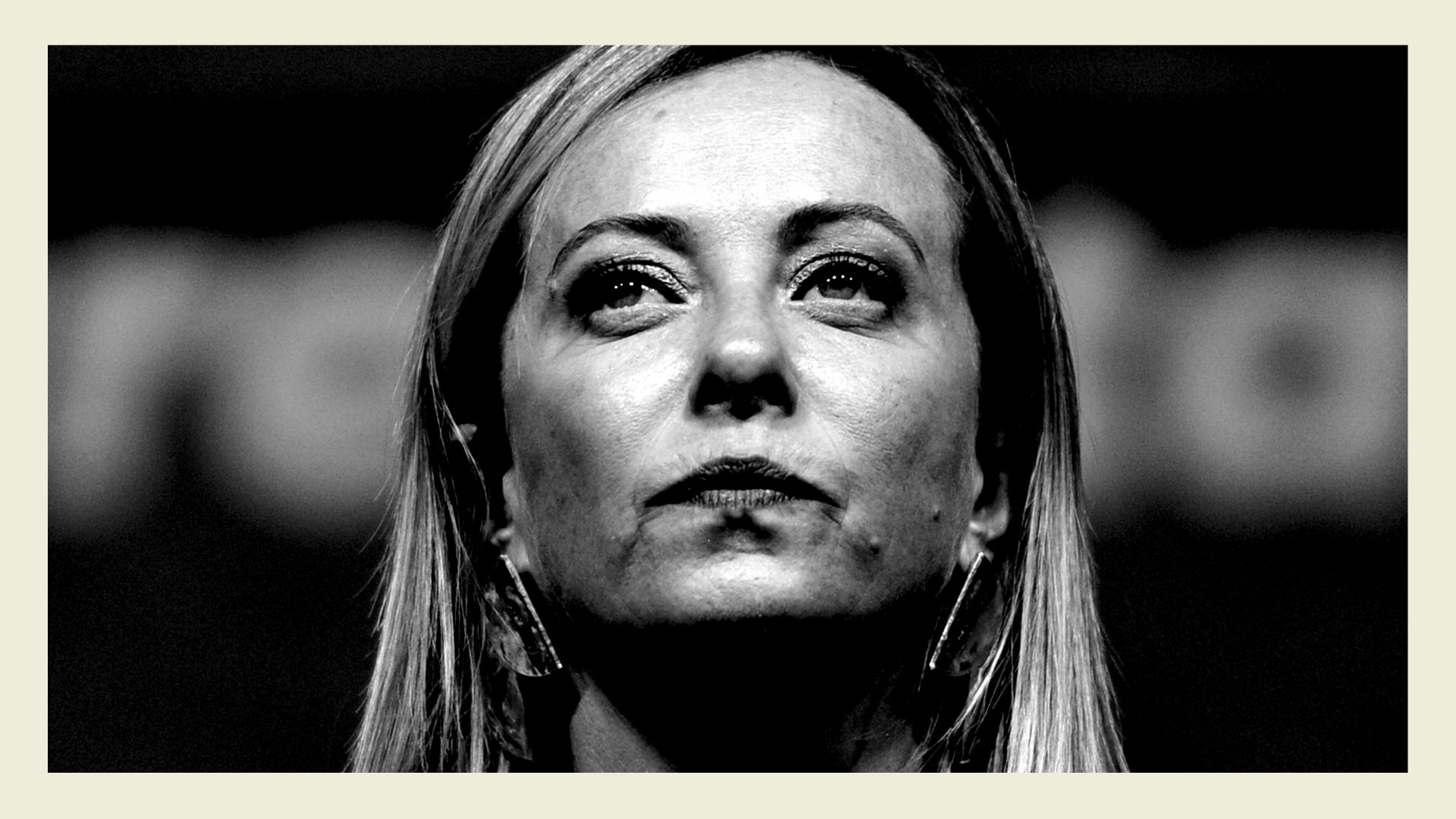

Under Andersson, there was an additional safety net for Kurds – a deal she had been forced into by Amiheh Kakabaveh, a prominent Kurdish MP. With parliament finely balanced, Andersson would have lost a confidence vote had Kakabaveh not abstained. She did so in exchange for a promise that Sweden would support the autonomous Kurdish administration in northern Syria, whose fighters had been central to the defeat of Islamic State. Now Andersson is out of office, Kakabaveh has left parliament and with the Sweden Democrats now in power, the deal is dead.

But according to Kakabaveh, even before the election, Sweden had already abandoned the Kurds, especially those fighting in Syria.

“It’s hypocritical, they betrayed us – they’re liars,” she exclaimed, with bitterness. “When they needed the Kurds to fight IS, the West made them heroes but now they need Erdogan, they’re some kind of terrorist. How are they not ashamed?”

***

Kurds first started moving to Sweden from Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria in the 1960s. First they went as migrant labourers, then as part of a global flow of opposition activists and political exiles who were attracted by Sweden’s culture of political openness and acceptance. They fled Saddam Hussein’s brutal crackdowns, Iran’s Islamic revolution of 1979 and a wave of discrimination and harassment in Syria. A stream of exiles came from Turkey, escaping the vicious left-right political violence of the 1970s, a brutal 1980 coup followed by martial rule, and the fallout from the Kurdish insurgency in the southeast. Erdogan’s oppressive second decade in power, and especially the witch-hunt that followed a 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, led to a new influx of both Kurds and Turks into Sweden, who were accused of working with Fethullah Gulen, the exiled Islamic cleric blamed for the failed putsch.

Many of these new Swedes were ordinary civilians, but some had borne arms against their states. Sweden welcomed the arrivals, partly due to the influence of the social democrat premier, Olof Palme, whose unsolved assassination in 1986 still grips the imagination. That killing has even had the Netflix treatment in last year’s release of The Unlikely Murderer.

Palme, who was prime minister between 1969 and 1976, and again in the 1980s, was a charismatic, polarising figure and a fierce critic of both US and Soviet foreign policy. He marched against the Vietnam war and was the first Western government leader to visit Cuba after the revolution.

His mission was to leverage his country’s neutrality to make it an international powerbroker and moral example. “Sweden’s foreign policy neutrality and free position between the super-power blocs has allowed us to develop a generous refugee policy,” he told parliament in 1979.

As their numbers grew, the influence of Sweden’s Kurds also increased. The increasing influence of Kurdish novelists, intellectuals, artists and politicians in Sweden led researchers at the Nordic Journal of Migration to describe Sweden as “the only Western country where the most advanced diasporic cultural activities take place among the Kurds.”

In contrast, many of the Turks who arrived tended to live more insular, less engaged lives – Swedish politicians found the more active Kurds easier to converse and identify with. They have publicly supported many prominent Kurdish movements and personalities. A former justice minister even travelled to an anniversary event for the PKK, which is proscribed as a terror organisation in Sweden.

Kurds have also moved into Swedish politics. Before last year’s elections, there were six Kurdish MPs in parliament, including Kakabaveh, whose story demonstrates the social mobility that Sweden has offered foreigners. Leaving her impoverished, illiterate family at 13, she joined Iran’s Komala peshmerga fighters, which sought greater Kurdish rights. Following death threats, she fled to Turkey and eventually arrived in Sweden as a refugee. She worked as a housemaid but then got her Msc in sociology and philosophy before becoming a progressive, feminist politician. In 2016, she was named Swede of the Year by the current affairs magazine Fokus.

“Kurdish women have a potential which turns them into innovators and leaders when they join European communities,” said Agnita Swanson, a Swedish activist, admiringly, as she presented the award.

The high profile given to Kurdish nationalists, including Nesrin Abdullah – a Syrian Kurdish commander who posed for photos with the former foreign minister Ann Linde – created resentment among the non-political Turks who live in Sweden. They felt overlooked, and their concerns were increased by propaganda on the Turkish TV channels they watched.

This resentment grew as Syrian Kurdish entities – the pro-independence Democratic Union Party (PYD) in northeastern Syria and its armed wing, the Syrian People’s Protection Units (YPG) – won fame and favour for acting as a proxy army for western governments in the fight against IS. The public loved media images of their women’s battalions – gritty Amazons wearing pink bunny socks. Turkey complained that nobody focused on the groups’ links with the PKK.

So when, following Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, Sweden decided to abandon 200 years of studied military impartiality and make a bid for Nato candidacy, it would have been a surprise if Erdogan had not tried to exploit this. So, inevitably, the man in charge of Nato’s second biggest army used his veto and refused to budge. Finland’s application for Nato membership was also affected. Since both Nato and the two candidates were desperate for accession, they caved in to Erdogan’s threats, agreeing to speed up extraditions and end the ban on arms sales to Turkey.

As well as going to the heart of the evolving problem over freedom of speech in Sweden, this decision highlighted the curious on-off Western relationship with the YPG, and with the Kurds in general. In a repeating cycle of disappointment, they have been supported and encouraged, only to be dropped when something else came along. One of the worst examples came in 2019, when Donald Trump pulled US troops out of Syria, abandoning the Kurdish fighters who had defeated IS, and leaving them open to assault from Turkish forces. Trump’s justification for the move, given at a press conference, was: “They didn’t help us with Normandy.”

Within hours of the Turkish-Swedish deal, Turkish media wrote that a 73-strong extradition list of high-profile Kurds was wending its way to Stockholm – although subsequent reports put this at closer to 30 or 40. On the list, according to reports, are exiles such as Ragip Zarakolu, an activist publisher of books on minorities, including Kurdish independence and the Armenian genocide, and journalists Abdullah Bozkurt and Bulent Kenes, whom Turkey accuses of supporting Gulen, the alleged coup plotter. Erdogan also demanded the deportation of Kakabaveh, who isn’t even from Turkey.

Håkan Svenneling, an MP for the Left party, told me that he now regularly fielded questions from Kurdish constituents worrying for their safety. “I don’t think extraditing the whole list is possible because many are in the spotlight. But there’s a definite risk.”

Kurdo Baksi, an award-winning Swedish Kurdish writer and social commentator, said he fears for a return to the time following Palme’s murder, when the PKK was blamed. “Swedish Kurds, desperate to be granted refuge here, were forced on planes bound for Ankara or Istanbul, crying over children and girlfriends, Kurds who dare not ever again spend their holidays outside Sweden’s border because Ankara is looking for them via Interpol,” he lamented. “The Kurds can be sacrificed, especially if one fears the Kremlin despot and seeks refuge in Nato. I sleeplessly fear that the nightmare of the 80s will happen again.”

Andersson said that she hadn’t promised anything that contravenes Swedish or international law, and that extraditions would only ever happen under Sweden’s rigorous rules. In practice, Turkey doesn’t have much luck internationally with its extradition requests, which are often ignored for lack of evidence. There have been some extraditions to Turkey, but they were for crimes such as fraud and not linked to the list.

“Many of the Turkish demands are unreasonable,” Paul Levin, director of Stockholm University’s Institute for Turkish studies told me. “Zarakolu’s a kind of lefty radical Santa Claus who has dared to publish stories critical of the government’s fight against the PKK, but it’s frankly absurd to accuse him of being a terrorist. That’s just one case. There are also old names circulated and rejected before – one man on the list had died years ago.”

Others on the list were Gulen supporters. But that’s not a crime in Sweden, since Turkey is alone in designating the cleric’s movement as a terror organisation. No credible evidence has been presented showing he or any of his members were involved in the coup.

Turkey’s demands were, in part, symbolic, political signalling to a domestic audience that the government is still tough on insurgents and their fellow travellers. All along, Sweden made clear that it didn’t fund or provide arms for any terrorist activities, with any money going to causes such as child-friendly NGOs in northern Syria, not the PKK or the YPG. And governments can’t override judges on extraditions.

Andersson didn’t help with a remark that Swedish nationals wouldn’t be extradited and that “if you’re not involved in terrorist activities, there’s no need for concern.” As Jonas Sjostedt, former leader of the Left Party, Tweeted: “In Turkey, entirely peaceful Kurdish activists, left-wing politicians and journalists are casually accused of terrorism.”

Now the fate of Sweden’s immigrants is in the hands of a government supported by a party that doesn’t like them. Two years ago, the SD’s young leader, Jimmie Åkesson, went to Turkey to give leaflets to desperate refugees with the following message: “Sweden is full. Don’t come to us! We can’t give you more money or provide any housing.”

With its influence, the hard right could pose a threat to immigrant communities at home too, especially to Middle Eastern ones, by putting a greater emphasis on crime and security, criticising multiculturalism and trying to reshape Sweden’s culture by creating state-owned media in their own image. The SD parliamentarian Björn Olof Söder said as much immediately after the elections. Söder has been publicly accused of anti-Semitism.

Despite a long period of detoxification and expulsions, it’s no secret that the Swedish Democrat party emerged from Sweden’s 1980s Neo-Nazi and skinhead groupings and the tone of its 2022 election campaign suggested that it has not left those roots behind. That campaign was conducted in a bitter atmosphere of quasi-xenophobia, in which even the left focused on immigration and gang warfare. The SD party was able to exploit Sweden’s failure to adapt to the multicultural society that the country’s welcoming stance has created – especially after it opened its doors to Syrian refugees in 2015, taking in more per capita than any other country in Europe.

Kakabaveh, a committed socialist and a refugee herself, has been warning of the dangers of opening the country’s borders to tens of thousands of new arrivals each year without providing more houses, doctors, teachers and social workers. This failure, combined with a deterioration of Sweden’s famous welfare state, helped to create the right-wing shift that boosted the SD to such an extent that even some immigrants voted for them. While the main parties mostly pitched for the middle class vote, the young, the suburban, the worker, the refugee and the poor felt ignored.

It didn’t help that communities of minorities, old and new, tended to group together in the suburbs of cities such as Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmo, in some cases effectively living segregated lives.

“I came to Sweden 20 years ago and apart from two years I have lived in a segregated area with immigrants from different countries – we used to look around and say ‘here is Damascus, here is Baghdad’,” Kakabaveh told me. This is no way to build a society. “Our kids don’t have the same education. They don’t meet Swedish kids until secondary school. State schools in the suburbs are very poor and don’t have good teachers.”

Large numbers of children leave school without qualifications. Disaffected youth sought meaning and belonging wherever they could find it, sometimes in extremist ideology. Kakabaveh said a friend’s son was first lured by a Muslim group, praying before and after school. At 16, to her horror, he joined a gang.

Gun crime has risen, with murders at a record high. The violence was often within the immigrant population – including Turks and Kurds – which made it highly visible, and politically sensitive.

The Kurds’ reputation was also tarnished by cultural horrors such as so-called “honour killings”, including the high profile murder of 26-year-old Fadime Sahindal by her father, soon after she had spoken in parliament about the death threats she received for having a Swedish boyfriend.

That killing was both a personal tragedy and a blow to Sweden’s cultural cohesion, especially as many of Sweden’s Kurds, like immigrants everywhere, just want to work and keep their heads down. Some of them support the Kurdish cause but have no links to the PKK and disapprove of its violent methods. Even Kurdish activists are running out of patience with the PKK, which they accuse of effectively running a protection racket against Kurdish restaurants in Stockholm.

Even though the Kurdish community is not monolithic, anti-immigrants make little distinction. As the number of Swedes with foreign backgrounds has risen, the seeds of anti-immigrant nationalism have been sown, helped by far-right disinformation campaigns often emanating from Russian or American nationalist websites. This change even began to seep into Sweden’s cultural mainstream – Henning Mankell’s internationally famous Wallender mysteries are laced with troubling signs of growing far right violence. During the election campaign, an eminent psychiatrist was stabbed to death by what newspapers said was a suspected neo-Nazi sympathiser.

But while worries over the future of Sweden’s dissident Kurds have focused on the deal with Erdogan on Nato membership, Paul Levin of Stockholm University points out that Sweden’s official stance was changing well before any of this. He sees an underlying trend.

“In July, Sweden’s new anti terror law entered into force. It sharpens the laws on terrorism and my understanding is that it expands the scope of potential activities that can be considered terrorism,” he said.

There was also a proposed constitutional change, Levin added. “This would additionally sharpen the definition of terrorism to include membership of a terrorist organisation and financing and so on, which are not considered crimes in Sweden today.”

These stricter rules have nothing to do with Turkish demands, but are the result of an internal Swedish decision to find ways of stopping IS volunteers from travelling, recruiting and raising funds. This could make life more difficult for the PKK and its supporters.

Leftist politicians also told me they’ve noticed increased collaboration between Turkish and Swedish security services, and an increase in deportations. In Svenneling’s constituency, a Kurdish baker’s son involved in mugging and drug crimes was sent to Turkey, where he was jailed for “terrorism”. Last year Zozan Buyuk, a Kurdish mother, born in Belgium and married to a Swedish Kurd, faced deportation for going on a protest march and showing sympathy for Kurdish groups including the YPG. Sweden has also tightened up its refugee policy, as announced with pride by former social democratic migration minister Morgan Johansson: “Sweden now has one of the most stringent refugee laws in the entire EU and therefore no longer functions as a magnet for refugees. It is difficult for them to get here at all now.”

Erdogan has overcome his objections and removed Turkish obstructions to Swedish Nato membership – but the Turkish leader never does anything unless there’s something in it for him. Next on his list is EU membership, a prospect that will no doubt trigger a reaction across the European far-right, including in Sweden. Nato membership for Stockholm may prove to have deep consequences for the continent.

*This article was originally published on 15 September 2022