Last Sunday night, Sweden experienced what felt like a political earthquake. After a calming exit poll, which indicated that prime minister Magdalena Andersson might continue in power, we felt the tremors – the centre-right Moderates dropping in the polls, and Jimmie Åkesson’s Sweden Democrats rising.

And then, late on, the Earth moved. With approximately 90% of the votes counted, it looked like Sweden might get a new government – a proposed right-wing coalition that would break new ground, in the worst kind of way, with the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats as its largest party.

To political seismologists, this has come as little surprise. The rise of the Sweden Democrats has followed the same trajectory as many other right-wing populist parties across Europe. If anything, it has taken them longer than most of their political counterparts to find common ground and cooperate with established parties.

There are reasons for that, however. The main cause has been their uncomfortable relationship with Nazism, a connection stemming from the party’s founders and running all the way up to its present-day representatives.

Not even the Sweden Democrats’ own white paper, which had its first part released earlier this year, disputes this connection. It confirms that the party was in effect created as a bureaucratic continuation of “Keep Sweden Swedish”, a far-right, openly racist campaign organisation modelled on the British National Front. Out of the 22 founders who feature in the report, ten have a background in Nazi organisations, among them Gustaf Ekström, a committed National Socialist, who in 1941 volunteered for the Waffen SS.

A decade later, another SS veteran, Franz Schönhuber, would pose for a smiling picture together with Björn Söder. Söder is one of the four men – alongside party leader Jimmie Åkesson, party secretary Richard Jomshof and chief ideologue Mattias Karlsson – widely credited with shaping the Sweden Democrats into what they are today.

Three of them joined before the party decided to change its former strategy of courting the white power skinheads, who were deemed a liability after a fiasco during the 1994 election. The fourth, Jomshof, would sign up a few years later.

The Gang of Four, as they’ve been called, met at university in Lund, a city in southern Skåne county. The local politics of Skåne, at the time, included several smaller right-wing populist parties. During the early 2000s they were absorbed into the Sweden Democrats, merging their anti-immigration ideologies into something very similar to what we see today.

At the same time, the party platform was reworded to be more moderate and some of the openly extremist ties were cut. In 2005 Åkesson took over as party leader, and the official logo was changed from a National Front torch in yellow and blue, to the similarly coloured hepatic.

In 2010 they crossed the 4% threshold that prevents fringe parties from entering parliament, and took 20 seats. Almost a decade would pass before any of the other parties would negotiate or cooperate with them on a national level.

During that time, the party was embroiled in near-constant scandals. Perhaps most shocking was “the iron pipe scandal”, where in 2012 a video leaked of three high-ranking politicians in a heated argument with a comedian of Kurdish descent. After yelling slurs at those present and shoving a woman against the side of a car, the three laughing men decided to arm themselves with metal scaffolding pipes “for protection”.

All involved would eventually leave political office. Two of them, who at the time were serving as the party’s financial and legal policy spokespeople respectively, are now active within the alternative media sphere that surrounds the party.

As well as this, hundreds of representatives, including those at the very top of the party, would be caught expressing racist, homophobic, sexist and otherwise intolerant views. Although many were supposedly expelled from the party as part of its claimed “zero tolerance policy”, others remained or were simply moved to lower-profile positions.

Yet, support for the party kept increasing, first from former Social Democrat voters, mainly belonging to the traditional working class and later in equal parts from Sweden’s second biggest party, the right-wing Moderates.

The party’s growth was helped by the fact that the political landscape had taken the shape of two easily defined blocs – one green, left-wing side and one liberal and conservative – and that all parties had moved ostensibly closer to the middle. That left plenty of room for an authoritarian actor to pick voters from both sides of the left-right spectrum.

In the 2018 election, the Sweden Democrats won 17.5% of the vote. Attempts were summarily made by several of the right-wing party leaders to make room for them at the negotiation table, but they were still met with media and voter disdain and the idea was quickly dropped.

The numbers, however, meant that the other parties felt compelled to adjust their immigration policies in line with the more restrictive ones suggested by the Swedish Democrats. The media narrative also shifted, to make up for what came to be seen as the elite’s dismissive attitude to widely held concerns about immigration.

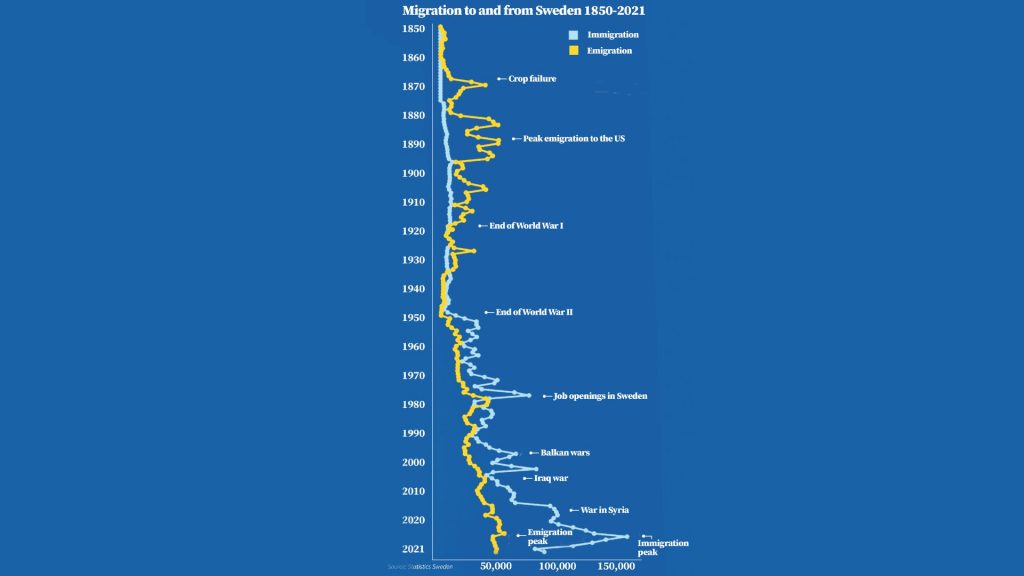

Sweden has always ranked high when it comes to the number of immigrants accepted per capita, and the 2016 refugee crisis was no exception. In the years that followed, right wing populists, including our own, worked hard on forging the narrative of Sweden as a land torn apart by Muslim asylum seekers, no-go zones, burning cars and rampant crime.

This was, as it often is, a gross exaggeration. But the idea stuck. Even today, in the recurring “What Worries the World” survey conducted by Ipsos, Swedes are number three on the list of which country’s citizens worry the most about crime, despite the fact that the actual crime statistics suggest that far less worry might be warranted.

Still, that worry was what the right wing chose to latch on to during 2019. While the two more liberal, centre-right parties chose to support a minority government led by the Social Democrats, the Moderates and Christian Democrats opened the door to cooperating with the SD once more, without walking it back this time.

There comes a point when the bandwagon practically drives itself. Politicians and media scrambled to push back on the suggestion they represented the naive establishment that was ignorant to the woes of those below their ivory tower. They ended up reinforcing the narrative they were trying to correct in the first place.

While the Moderates and Social Democrats – the latter inspired by their Danish colleagues – might have thought that adopting some of the populist talking points could win them their voters back, polling seems to suggest it had the opposite effect.

In this election year, the Sweden Democrats have experienced several scandals. Another 214 of their representatives have been connected to right-wing extremism. The party’s defence policy spokesperson was even accused of spreading pro-Russian war propaganda. But despite all this, the Moderates now find themselves the third largest party rather than the second.

That matters, since they’re planning to go into government together. Traditionally, the party leader of the largest party in the coalition will claim the role of prime minister – something that could become a powerful bargaining chip for the Sweden Democrats.

Before the election they were demanding seats for their political officials, which in itself is a frightening idea. But now, if they’re the largest party in the coalition? Who knows what their claims will be, how the three other parties will respond to them and how much influence the Sweden Democrats might have over the government.

Regardless, the outcome is likely to be bleak. Their reaction to the other parties adjusting their positions to accommodate them, so far, has been for the Sweden Democrats to move their own position as well. They have taken it back to their roots. This has resulted in comments from the very top of the party about putting Afghan immigrants on repatriation trains and how Muslims don’t belong in Sweden, as well as an increasingly lax stance against extremists in and around the organisation.

The Sweden Democrat party that will start coalition negotiations this week is far from the reformed version the public has been promised. Rather, it’s more openly extreme than it has been in nearly a decade. And that responsibility rests solely on the Swedish right-wing establishment for their naivety.

Myra Åhbeck Öhrman is a Swedish writer and podcaster