We all like mysteries, and Nigel Farage loves to provide them. His absence from Reform UK’s new year press conference provoked dramatic headlines. Where was he? Why wasn’t he there? Is he at odds with Richard Tice, Reform’s leader?

The answers matter not just to the state of Reform, but to the outcome of the coming general election. So what is really going on? Are the two men actually fighting, or simply teasing us by acting out a script whose agreed denouement is Farage’s return to frontline political battle?

The key thing is that Reform UK is not a conventional political party. It is a registered company, “Reform UK Party Limited”. Eight of the 15 issued shares in the company belong to Farage. Tice has five of the other seven. (Michael Crick, Farage’s unauthorised biographer, tells me that Tice confirms Farage is still the majority shareholder.) Farage has the sole legal right “to appoint and remove directors”. Tice leads the party, but Farage owns it.

This means that if Tice and Farage fall out, Tice will have to go. However, Tice has lent Reform around £1m and could demand its return, at which point Farage would need new, big donors. Without them, Reform would be broke and any chance of influencing the next election would be gone. Farage could end up as the undisputed owner of a political corpse.

But what if we are witnessing the carefully crafted choreography of Farage’s step-by-step return as the frontman for right wing populism in Britain? One clear lesson from the past 20 years is that Farage has a special ability to appeal to disgruntled voters, and without him, the nationalist cause struggles to win votes.

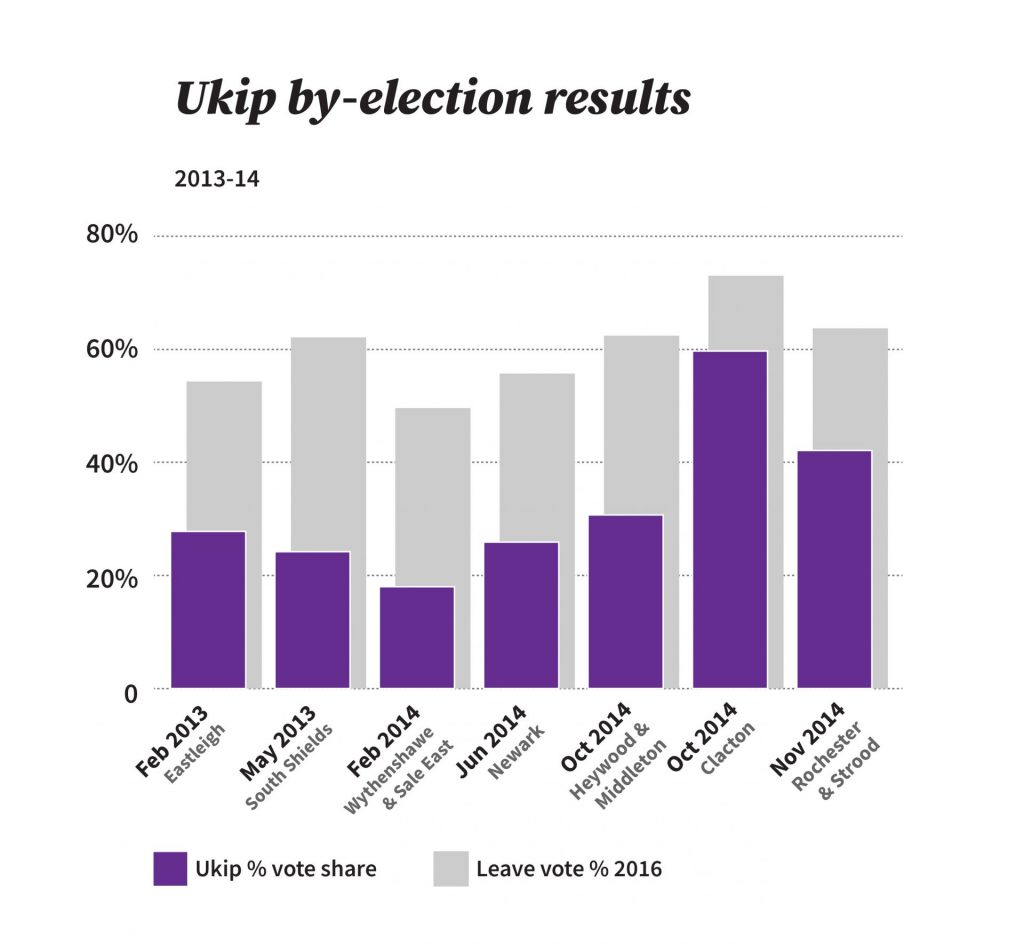

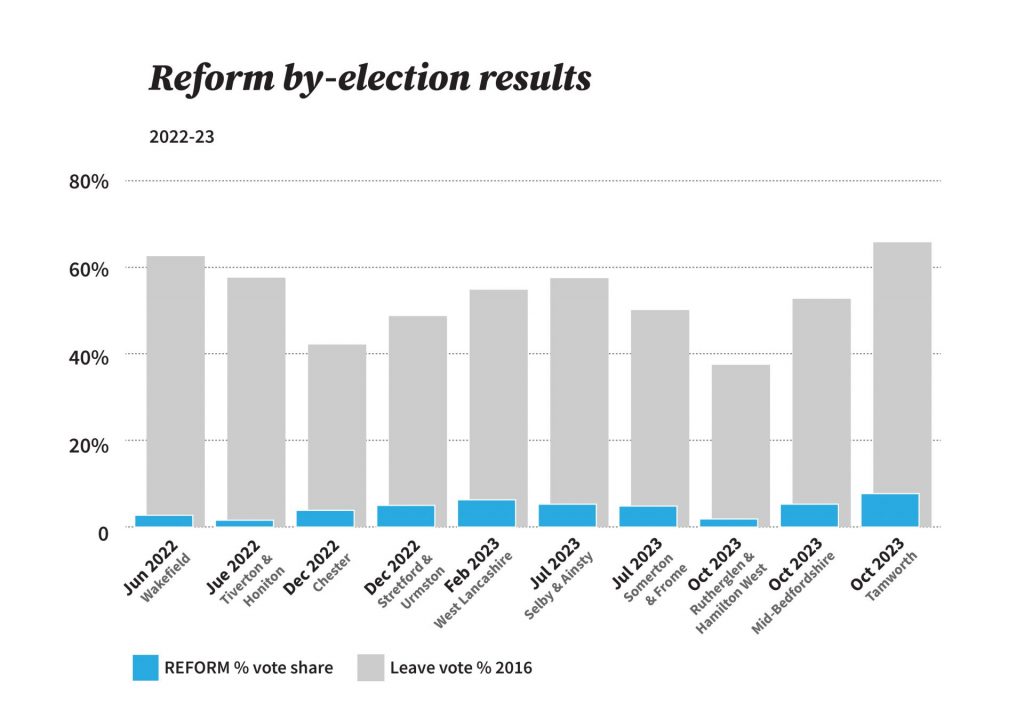

We see this if we compare the performance of Ukip and the Brexit Party under Farage’s leadership with Reform’s recent electoral record. Farage’s record in European Parliament elections from 2004 to 2019 is formidable. However, we have left the EU and there is no way to judge Reform by that yardstick.

There is, though, one comparison that can be made. A decade ago, when David Cameron was prime minister and Britain was heading towards the 2015 general election, Ukip candidates were a familiar feature of parliamentary by-elections – just as Reform candidates have been in the past two years. Below are the figures for Ukip in the second half of that parliament and Reform since the midway point in the current Parliament. The figures speak for themselves. Compared with Ukip in its glory days, Reform’s performance has been pathetic. (The same has been true in the annual rounds of local elections. In 2014, Ukip gained 163 council seats; in 2023, Reform gained just two.)

A secondary point is worth noting. There is a reasonably clear link between Ukip’s by-election vote in 2013-14 and local support for Brexit in the 2016 referendum. The more anti-EU the constituency, the better Ukip did. This pattern was repeated in the 2015 general election. Today, there is no more than the faintest hint of a Brexit effect on Reform’s record.

Now, it could be argued that Reform’s weak performance has nothing to do with Farage’s absence. Brexit has happened. Farage won that battle, but it is now over. None of the main parties are calling for it to be reversed, and while polls show an increasing number of voters think leaving the EU was a mistake, they also show that the issue is now seen as less important than a host of others – including the state of the economy, the NHS, crime, the environment and housing.

Maybe in some years’ time, Europe will once again become a central issue in British politics. Until it does, swing voters will pay more attention to other issues. That is, after all, precisely why Farage changed the name of his party from “Brexit” to “Reform”.

Of course, there remains the issue that Farage has put at the heart of his anti-EU politics: immigration. Ten years ago, Ipsos found that it frequently topped the league table of Britain’s most important issues, ahead of the economy and the National Health Service. Ipsos’ latest survey puts immigration fourth, on 22%, well behind the economy (38%), inflation (35%) and the NHS (31%). That 22% is still a lot of voters. But whereas a decade ago, “taking back control” was a potent message for anti-immigration voters, Reform can offer no such apparently simple and seductive notion.

So it is not hard to explain why Reform has struggled to make an impact. Some polls are reporting that its support has picked up, and now stands at around 10%. But this would almost certainly leave the party without any MPs; and even this support could well be squeezed – as happened to Ukip in the months leading up to the 2015 and 2017 elections, and to the Brexit Party in 2019.

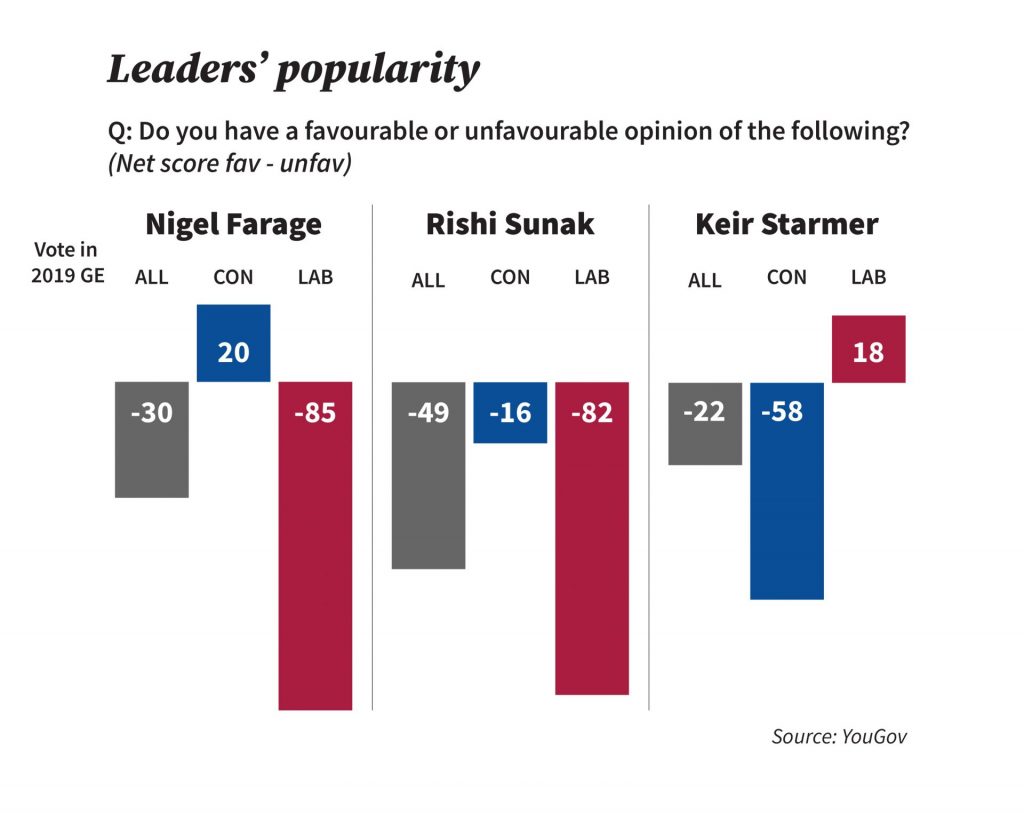

Which brings us back to Farage. Would his re-emergence as the public face of Reform make a difference? The polling evidence suggests it would, and the main reason is that Reform in its current Tice-led condition is far less popular than Farage.

Shortly before Christmas, Ipsos found that only 15% of the public had a favourable opinion of the party. However, a YouGov poll at around the same time found that Farage had a far better rating – and scored better than Rishi Sunak among people who voted Conservative. The data is available in different parts of YouGov’s website, but, as far as I know, has never been brought together (see below). I have added in the figures for Keir Starmer, as these are relevant to Reform’s impact on the next general election.

The figures for those who gave Boris Johnson his big victory four years ago are astonishing: a negative rating, minus 16, for Sunak among Tory voters, but a strongly positive rating of plus 20 for Farage.

Another poll, this time by More in Common, asked a different question and the results were not quite as bleak for the Tories, but still pretty dreadful. Asked who would make the better prime minister, Sunak or Farage, those who voted Tory last time divide 60-40% for Sunak: a majority, but not overwhelming.

When Labour voters were asked the equivalent question naming their leader, they opted for Starmer over Farage by 80-20%. Combine that with the fact that just 6% of Labour voters tell YouGov that they have a positive view of Farage, and it’s clear that any boost for Reform from Farage’s return would be overwhelmingly at the expense of the Conservatives.

So the direction of travel is clear: Farage’s return would mean more votes for Reform, mainly at the Tories’ expense. What is less certain is how big that boost would be.

An initial figure from YouGov is four points. In late November their conventional voting question put Reform on 10%. The same people were then asked two questions that named all the main party leaders – in one case with Tice as Reform’s leader, the other with Farage. Tice’s name added one point to Reform’s share; Farage’s name added four points, putting Reform on 14%.

Looking at these figures in more detail, we find that Farage’s main impact is among those who voted Tory in 2019 but now say “don’t know”. In the conventional voting question, this amounted to 23% of all Tory voters. With Farage as leader this falls to just 16%, while the proportion of last-time Tory voters who would support Reform under Farage jumps from 14 to 23%. That nine-point increase is equivalent to well over one million voters – an average of 2,000 per constituency, though the number will vary from seat to seat.

At first sight, this does not look too threatening to the Conservatives. If all that Farage achieves is to move 2,000 voters in each seat from staying at home to voting for a losing Reform candidate, it will make no difference to the number of Tory MPs who lose their seat.

Sunak’s problem is that his biggest target group by far consists of those voters who elected Johnson in 2019 but who tell pollsters they don’t know how they would now vote. Tory stay-at-homes have also played a big part in recent Tory by-election disasters. Their return to the Tory fold in the general election is crucial to any chance of making it a close contest, let alone keeping Starmer out of Downing Street. YouGov’s figures suggest that Farage has a far better chance than Tice of blocking their return to the Conservatives.

Which seats should concern Sunak most? This is hard to say. The seats with the biggest Brexit Party votes at the last general election were all won by Labour. With the possible exception of Hartlepool, which the Conservatives gained at a subsequent by-election, I would be surprised if the Conservatives put any effort into capturing any of them. Even if they vote Reform in above-average numbers in these seats, they will not affect who wins them.

One might assume that Reform will have the biggest impact in the Tory seats with the smallest majorities. On the new boundaries, super-marginals include Bury North (notional Conservative majority of 195 in 2019), Dagenham and Rainham (305 – a Labour marginal on the old boundaries) and Bolton North East (334).

But on any significant national swing to Labour, the Conservatives will have no chance of holding any of them. It is particular seats that the Tories will be defending much larger majorities – somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 – that will turn out to be the super-marginals next time, and where Reform’s impact could matter most.

After the next election, we shall be able to identify any such seats that Farage and Reform have helped Labour to win. In advance, the Tories will be fighting a giant game of Whac-A-Mole with a blindfold: in each seat where they put a huge effort to suppress Reform, another vulnerable seat will pop up, and the Tories can’t be sure where it is.

It is this local uncertainty as much as Reform’s overall national appeal that should terrify Sunak – and gravely limit his ability to fight back effectively on the ground.

His only hope in seeing off the Reform party threat is that Tice and Farage fall out.

Peter Kellner is a political commentator and former president of YouGov