For better or for worse, I watched Adam Curtis’s Russia 1985-1999: TraumaZone cold. Until now, I’ve managed to skip the debate about whether Curtis is a creative genius playing six-dimensional chess or a highly skilled

editor who happens to be a one-trick pony. I’ve done this simply by mostly

skipping the documentarian’s work, from Can’t Get You Out of My Head to

HyperNormalisation.

What everyone seems to agree on is that Curtis is Marmite; you either love or hate him. After watching his latest project, I understood why.

Unlike the slow, fatal declines suffered by other empires, the collapse of the Soviet Union came suddenly and traumatically. Left behind was a wave of fierce anger and deep-rooted scars within Russian society that, arguably, set in motion a course of events that led to the war in Ukraine.

It is this series of events that make up Curtis’s TraumaZone. Through seven hour-long instalments, Curtis conveys how rising scepticism challenged any

lingering belief that, first the Kremlin could successfully deliver the style of

communism as pledged by Marx and, second, that democracy would bring its own promised land. It details how two different utopias eluded the grasp of the Russian people.

The anger is clear to see from the start. “If you had a wish, what would it be?,” one interviewer, hidden from the camera, asks a woman who is

despondently and unsuccessfully trying to put up wallpaper in her Moscow flat. To the struggling decorator, it is a redundant question – she responds that she doesn’t have any wishes, but even if she did, they wouldn’t come true. Wishing relies on a sense of belief that she lost long ago. In fact, she adds with a curious smile, that changes the scene’s tone, she doesn’t believe in the reporter, either.

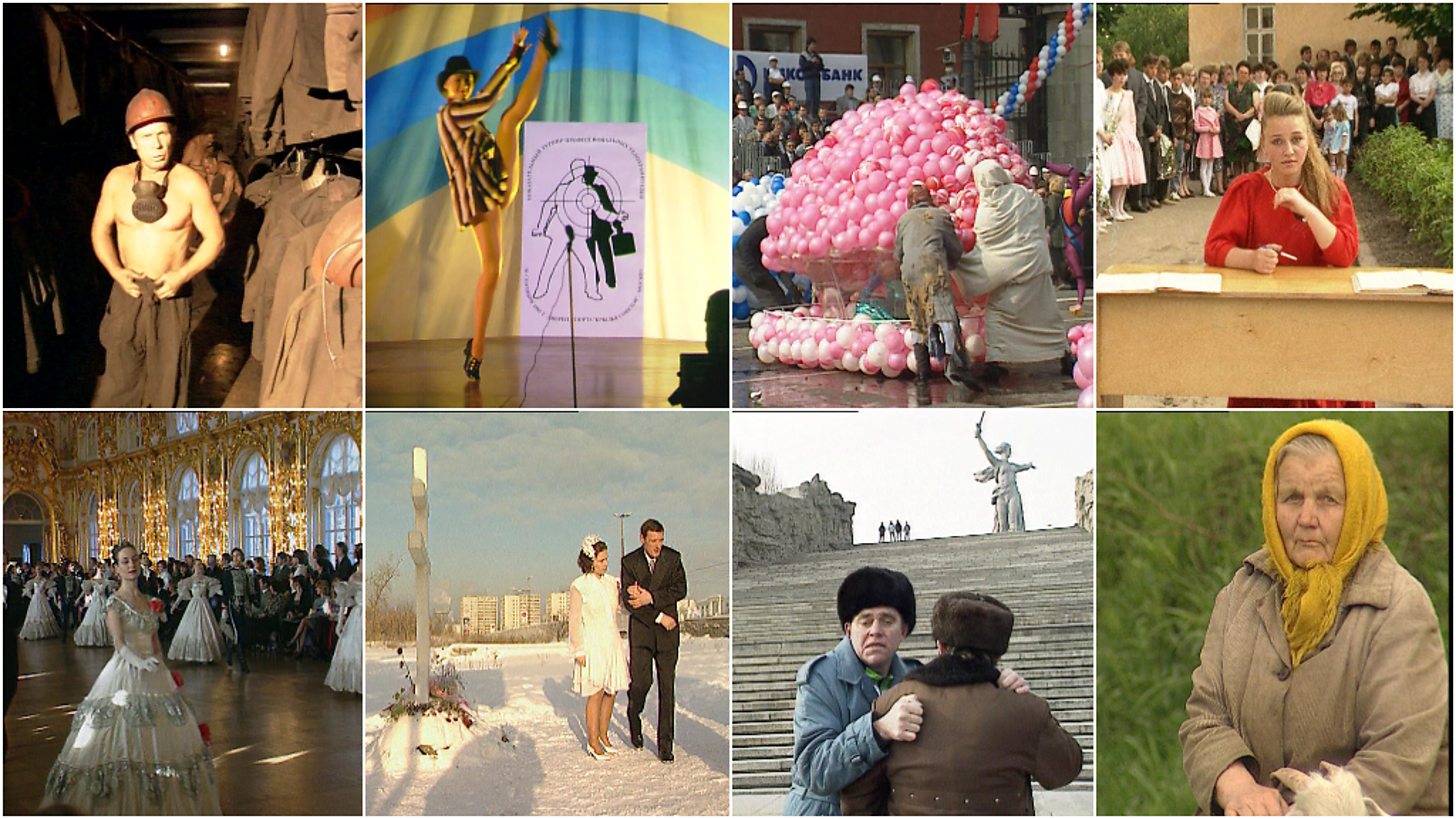

Another thing everyone can agree on about Curtis is that there is no filmmaker quite like him. TraumaZone features a stunning array of hundreds

of previously unseen clips from BBC Moscow’s staff, taken from 10,000 unedited “rushes” over 35 years of filming. From striking miners to beauty

queen wannabes, Curtis presents a carefully crafted picture of an era when

the illusion of communist competence and then the dream of western-style

liberal democracy was shattered.

Once the opening credits roll, Curtis’s class is in session. He argues that nihilism was born out of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, a restructuring of the nation’s economy which gave managers of big industrial plants some

freedom from Moscow’s control. This was designed to salvage communism but instead, Curtis says, it created an economy of crooks. After Gorbachev

announces the policy in a speech at a car factory in Samara Oblast, Curtis cuts to a group of ghoulish gangsters primed and ready to loot the Ladas the

second they come off the assembly line. As the caption informs us, the managers had opted to use their newly granted freedom to flog cars to crooks and a black market was the result. Curtis’s takeaway lesson? Communism was dead, and the Kremlin had provided the murder weapon.

Due to their nature, insults are subjective. By TraumaZone’s final episode, it becomes evident that by the end of the 1990s there was one word sure to offend any Russian – “democrat”. According to the Russian TV journalist, Yevgeny Kiselyov, the word had become so derogatory after ten years of grappling with the system of governance that being associated with it was a failsafe way to insult someone. In his own words, “democracy was a curse”.

His assessment is delivered into the narrative at an opportune time by Curtis. Watchers have just seen Putin rise to power thanks to the oligarchs

(“he would be their creature”). They‘ve seen rehearsals for the Miss Army

Beauty Final. And they’ve seen a teacher hand out booklets to schoolchildren with page after page of propaganda on what an exemplary president Putin would be, paired with cartoons and a timeline of his life decked out in bright and cheery primary colours. What they haven’t seen is much context to go along with the spectacle, though an absence of voiceover means there are fewer of the narrative leaps that so enrage Curtis’s critics. The arc of the series invites comparisons with recent economic experiments closer to home, where the Liz Truss regime collapsed even quicker than the end times USSR.

If Curtis is documentary filmmaking’s answer to Marmite, it seems apt that my takeaway from the seven-part series is binary. There is no denying the eye-opening power of footage that shows how modern-day Russia was formed out of the ashes of an empire and how ordinary Russians, and the rest of the world, then had to fit themselves into a reassembled picture. But was I won over by the eclectic way in which it was presented? In other words, in just one watch had I become a Curtis fan?

Sadly, the announcement of future Curtis projects will inspire in me the same sense of despondency felt by that Moscow woman struggling to

wallpaper her flat. The footage he has curated and assembled makes for

essential viewing, but arguments about substance over style remain.

Curtis is sometimes accused of painting things in straightforward black and white. It seems fitting then that this judgment of his latest work should reside in a grey area.

Russia 1985-1999: TraumaZone is available on BBC iPlayer