The Office for National Statistics has published a new report on the impact of strikes, just as the government is attempting to wind up a false sense of outrage about the country “grinding to a halt”.

Since Rishi Sunak’s new anti-union legislation is based on that idea – and the idea that a grateful nation will thank him for stopping communist union barons from holding them and the country to ransom – it is a timely publication.

Its main findings, however, do not quite support the government’s narrative of a Britain locked down by the descendants of Arthur Scargill and Red Robbo. Instead, the ONS found evidence that:

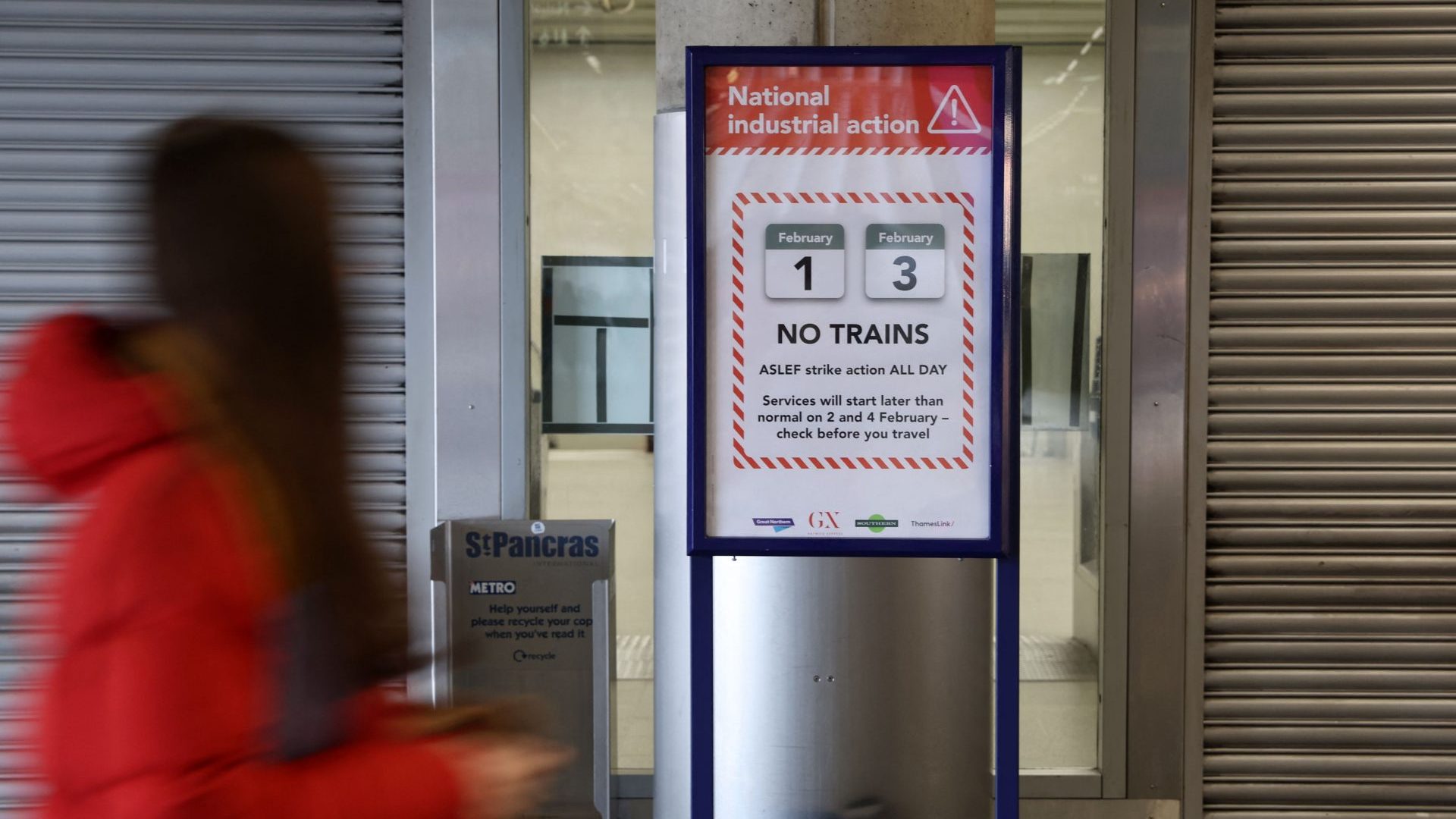

Rail strikes led to the displacement of card spending towards buses and taxis as consumers changed their behaviour to mitigate the impact of strikes;

In-store transactions at Pret A Manger stores located in stations fell on most strike days;

Nearly one in five people reported having their travel plans disrupted by rail strikes that occurred in December 2022 and early January 2023; but

Fewer than one in 10 of those disrupted were unable to work.

Forgive me but moving spending from non-existent rail services to buses is not a catastrophe while falling sales at Pret a Manger outlets at train stations on “most” rail strike days is not really a reliable indicator that the country is grinding to a halt or even slowing down at all. Meanwhile, one-tenth of one in five is just 2%. So, it was only one in every 50 workers who found themselves unable to work, while 98% of all workers were fine. Once again not a huge setback, economically speaking.

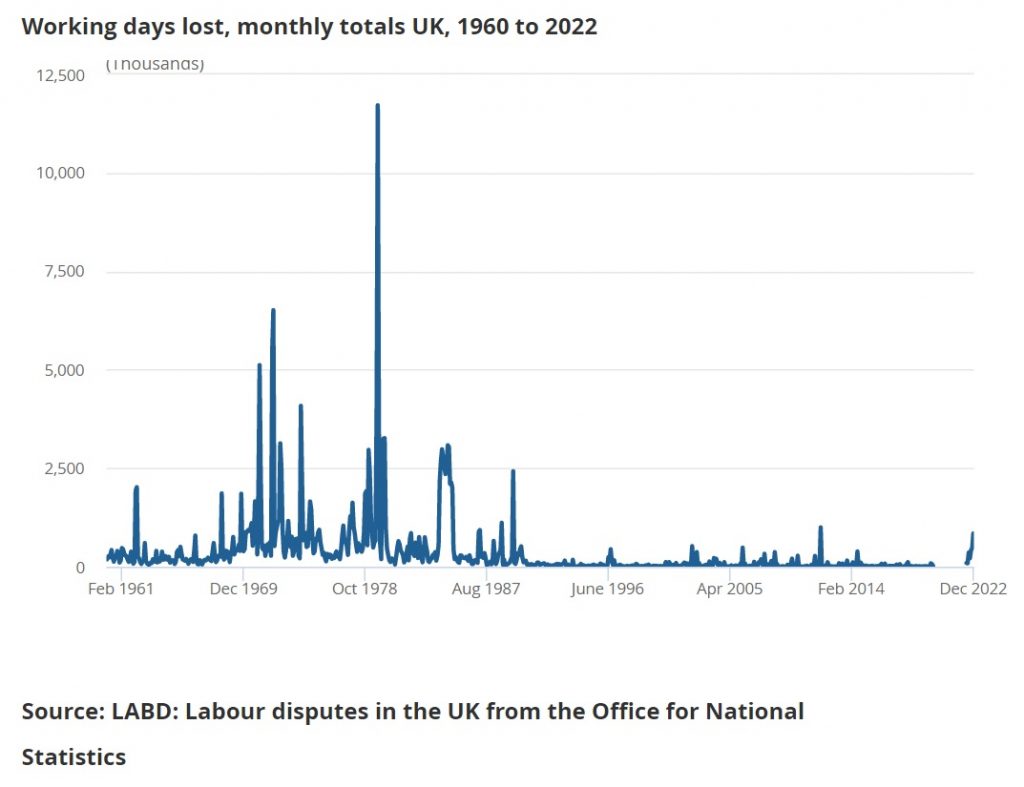

It is even nicer of the ONS to publish a very useful chart of the days lost to industrial action which shows that this surge in militancy is hardly visible on a graph that includes the Winter of Discontent in 1978-9 and the miners’ strike of the 1980s.

We have all, it seems, also become more flexible since the 1970s.

According to the ONS, it also found that on strike days people may choose to work from home or change the timings of their travel plans. Where possible people may change their spending behaviours if they have chosen to work from home. That when children are out of school because of industrial action, parents or guardians may be unable to work to provide childcare and when postal services are disrupted, individuals may choose to purchase goods in person or switch to other postal delivery services, or delay or bring forward purchases.

In short, while the government’s decisions continue to cause harm to Britain’s businesses and citizens, the ONS struggled to find any real evidence that the strikes have caused many people many problems, or had any measurable effect on the UK’s economy at all.

It is perhaps then, not the ringing endorsement of the government’s anti-union legislation that ministers might have hoped for.

Frankly, I am rather surprised it saw the light of day.