One freezing Berlin night in the mid-1990s, I was standing outside the Tränenpalast near Friedrichstrasse station on the banks of the Spree, halfway through a tour of Germany with a long-forgotten band. It was our only night off in a two-week itinerary and I was meeting a girl who was far too cool for me.

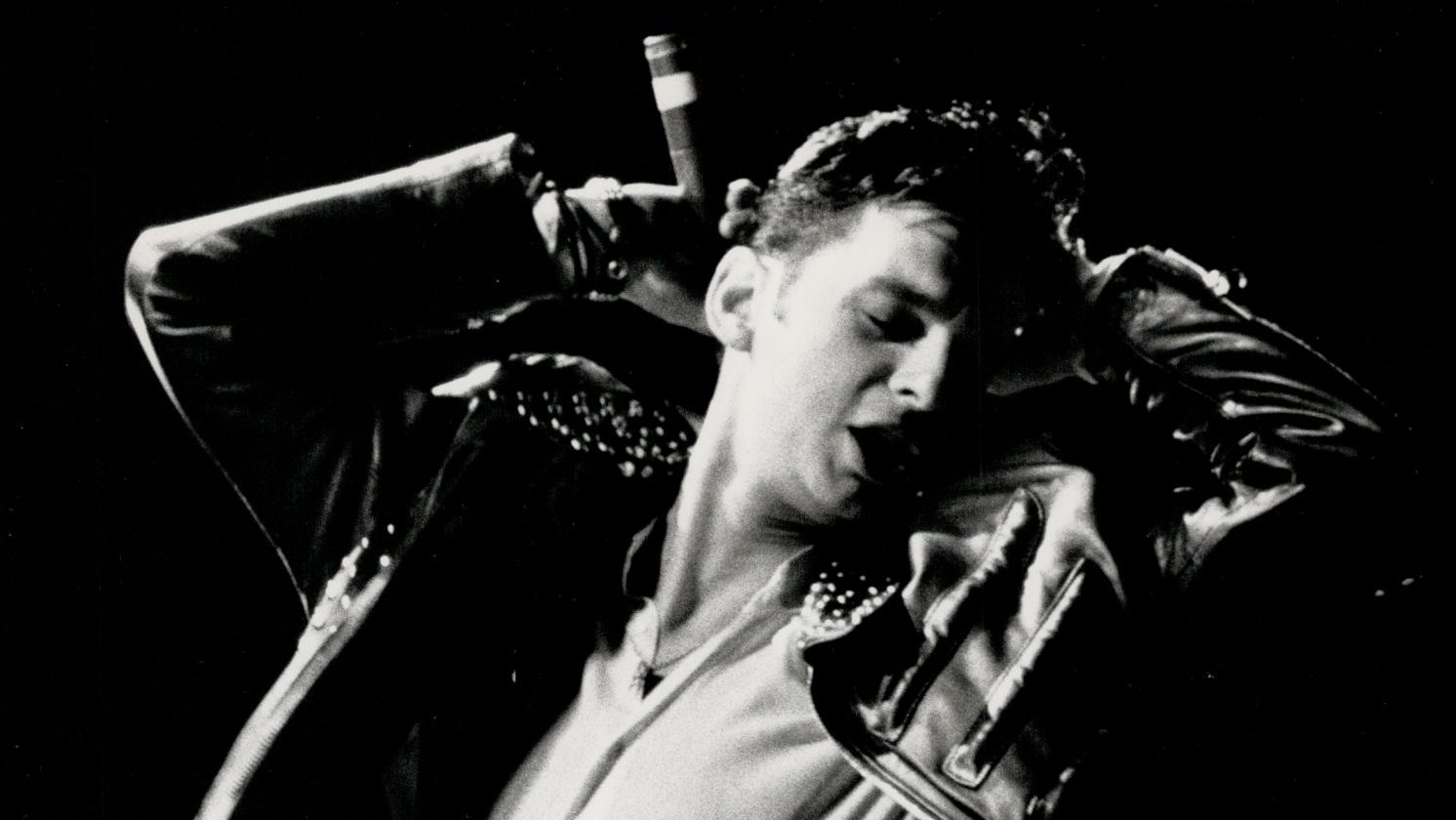

“This is a cool place”, the cool girl told me when she arrived, “with cool bands and stuff”. I followed her into a vast, echoing hall where a psychobilly band was playing at ear-splitting volume, the fast slap of the upright bass and the twang of the guitars bouncing around the walls and disappearing up into the high ceiling.

Everything was painted black, even the windows, and everyone was dressed in black. The cool girl disappeared briefly and returned with two large bottles of beer, dripping from where they’d just been bobbing in a dustbin of iced water, handed one to me and led me through the crowd towards the stage. I tried to think up interesting things to say in the gaps between songs.

“Amazing place,” was one of the more original observations I came up with. She leaned in to my ear and shouted above the din, “Ja, it’s very significant for Berliners. This was originally a checkpoint where people would leave East Berlin for the West. Some of them for ever. They would say goodbye to their families in this room.”

She leaned back, then leaned in again. “That’s why it’s called Tränenpalast,” she shouted. “It means ‘the palace of tears’.”

Swigging my giant bottle of beer I looked around a room filled with earnest-looking young punks, some nodding along to the band, a few nearer the front pogoing, and tried to imagine what these walls had witnessed under a regime that had ended barely five years earlier. I thought about the heartrending exclamations of emotion that would have echoed around walls now throbbing with turbocharged rockabilly, the lives upended, the families torn apart, the impossible clash of dreams realised and shattered.

I felt suddenly overwhelmed by how many stories must have unravelled or begun in this hall, a vast cavern once impervious to compassion but now harnessing the raucous howl of an uncertain future.

I wanted to convey all this to the girl who was too cool for me, to impress her with my understanding of the building and her city, in which I was spending only my second night. I needed to find exactly the right words. I leaned towards her and she turned her head to listen.

“Blimey,” I said.

Fortunately Berlin, the ultimate European city of stories, has been better served by more eloquent commentators than me. The concrete schism that sliced through the heart of the city for almost four decades has inspired some extraordinary writing by itself, while the wider 20th century in particular saw Berlin established as one of the most literary cities in the world.

If we can pinpoint one moment as being crucial to this, at least for the Anglophone world, Christopher Isherwood’s arrival in March 1929 is probably it. Seeking a release from the stifling moral mores of 1920s England, Isherwood came in search of adventure, notably sexual adventure. The city was at its bohemian peak and, with the encouragement of WH Auden, Isherwood threw himself into its wilder excesses.

Within a few months he had settled in the Schöneberg district, inhabited by the oddballs and eccentrics that would fill works like Mr Norris Changes Trains and particularly his masterpiece, Goodbye to Berlin.

“I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking,” Isherwood wrote in the opening passage. “Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.”

And so began in earnest Berlin’s golden age as a canvas for the imagination, of outsiders as much as inhabitants in a time of permanent flux, the city an intoxicating mixture of wild abandon and excess, repression and oppression. Berlin became the political fault line of a continent, a city pushed, pulled and divided by political extremes and extremists yet always drawing in the poets, drifters and dreamers looking for a place to belong.

Goodbye to Berlin was published in 1939 and served as an elegy for a Berlin already disappearing when Isherwood arrived.

“Here, screaming boys in drag and monocled, Eton-cropped girls in dinner-jackets play-acted the high jinks of Sodom and Gomorrah, horrifying the onlookers and reassuring them that Berlin was still the most decadent city in Europe,” he wrote of the early-30s Eldorado club in his 1976 memoir, Christopher and His Kind, an accolade challenged often but never truly relinquished. Indeed, a thrumming undercurrent of decadence and hedonism runs through the city even today.

Just as Isherwood was arriving in Berlin, Alfred Döblin was publishing his masterpiece, arguably Berlin’s finest literary portrayal of all. 1929’s sprawling epic Berlin Alexanderplatz follows a man just released from prison after being jailed for beating his lover to death, and attempting to go straight by selling newspapers on Alexanderplatz.

Inevitably he is drawn back into the underworld that made him, of con artists and pimps, a world that would cost him his arm when a robbery goes wrong, yet a world he would survive to realise that, like Isherwood, he never truly belonged in the first place, the city leaving him “sniffing the air, sniffing the streets, to see if… they will still accept him”.

Berlin Alexanderplatz is violent, unsettling and filled with despair, yet also warm and hopeful, its characters bubbling and fizzing through a narrative as exhausting as it is exhilarating. It is the city itself captured between the covers of a book: Döblin has the reader looking out across the Berlin skyline and hearing all its stories, all its voices, all the dreams and hopes and failures and disappointments gathered and organised into a polyphonic triumph of a novel.

As Michael Hofmann, who made the definitive English translation of the book, put it, Berlin Alexanderplatz affirms “the literary name and fame of the city of Berlin, if not the idea of modern city literature altogether”.

Like Isherwood, Döblin was an outsider in Berlin, albeit one of a different degree: born in what is now Poland, he moved to the city with his mother and siblings when he was 10 years old and his father had abandoned the family for America and a lover. If Berlin was the ultimate projection of Isherwood’s sexuality, for Döblin it filled the void left by his father.

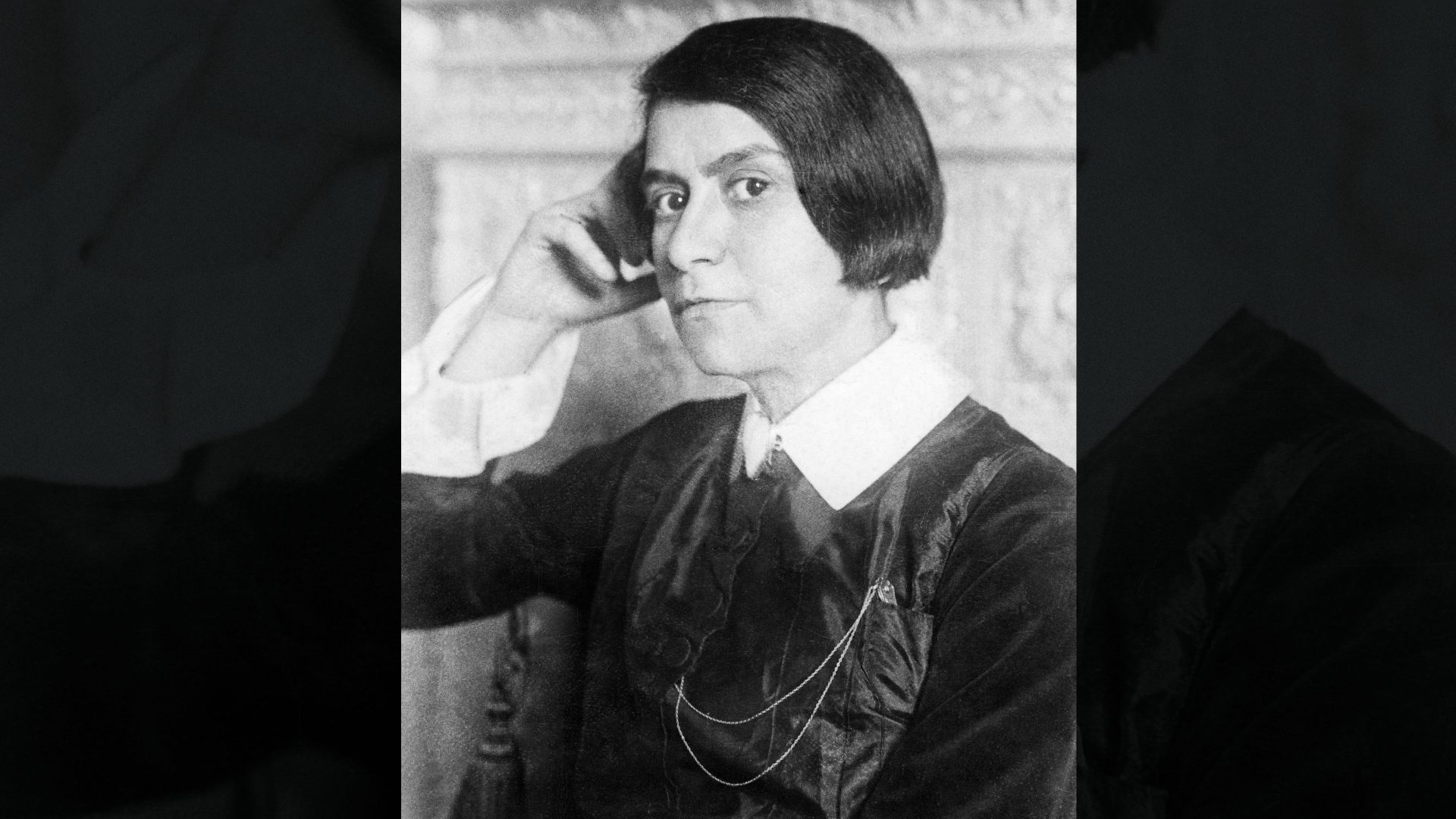

One novel from this period that is unfairly overlooked is Das kunstseidene Mädchen published in 1932 by Irmgard Keun and translated into English as The Artificial Silk Girl. Keun’s second novel is another outsider tale in which Doris, a woman in her late teens, flees her Rhineland home town after a scandal and washes up in Berlin, where she experiences every aspect of the Weimar city, mixing with business moguls and pedlars, experiencing the city’s heart at its blackest and its warmest.

Of life in Berlin under the Third Reich perhaps the best novel is one that enjoyed an unexpected renaissance when translated into English in 2009, Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin. First published in 1947 as Jeder stirbt für sich allein – “Every Man Dies Alone” – Fallada’s novel is based on a true story of how a quiet, middle-aged Berlin couple with no interest in politics until their soldier son is killed in France begin distributing postcards around the city urging people to stand up to the Nazis.

A beautiful, quietly joyous work that conjures everyday life in the city during the second world war, Alone in Berlin will break your heart.

The divided Berlin of the cold war, which Khrushchev described as “the testicles of the West – when I want the West to scream I squeeze on Berlin”, produced arguably the city’s richest vein of literature. John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came In From The Cold is rightly praised, a novel whose grim chill works its way right into the reader’s bones, but other works have richly evoked Berlin’s divided years. Ian McEwan’s 1990 novel The Innocent, for example.

Set in the mid-1950s, The Innocent revolves around a genuine MI6 and CIA joint operation to tunnel under Berlin’s Russian sector to tap Soviet phone lines. An English operative involved in the plan falls in love with a German woman in what Michael Wood in the London Review of Books called “a haunting investigation into the varied and troubling possibilities of knowledge”.

Peter Schneider’s The Wall Jumper meanwhile, set in the 1980s, criss-crosses the Berlin Wall to eavesdrop on people on both sides, a warmly human work that captures the hopes, dreams and disappointments that came and went during the structure’s 28-year existence.

The post-Wall generation have also produced some memorable and too often overlooked Berlin literature. In 2017’s Slumberland, Paul Beatty followed up his Booker Prize-winning The Sellout with a brilliant comedy, a joy of a book, set just after the fall of the Wall about a DJ seeking a semi-legendary avant-garde jazz musician last heard of in East Berlin.

In Sven Regener’s 2001 Herr Lehmann, meanwhile, which was translated into English as Berlin Blues, a slacker barman approaching the age of 30 in 1989 finds his carefully curated indolent life in Kreuzberg upended by a series of complications unconnected to world-changing events occurring nearby. A wonderful evocation of the city on the cusp of tumultuous change.

More recently, there have been two standout novels that capture the modern Berlin. East Berliner Jenny Erpenbeck was 21 when the Wall came down, lending her a perspective that makes her one of Germany’s most insightful novelists.

Gehen, ging, gegangen in 2015 (Go, Went, Gone in its English translation) is a brilliant examination of Germany’s refugee crisis seen through the eyes of a university professor increasingly drawn to the tent city on Oranienplatz founded by African asylum seekers.

In 2022’s Marzahn, Mon Amour, meanwhile, Katja Oskamp produces an affectionate portrait of the eponymous Berlin district through conversations between the middle-aged chiropodist narrator and her clients. It is a small, quiet book, but a vivid harnessing of stories from a range of lives made and shaped by a city that is itself shaped by stories.

Sometimes when I think back to that night at the Tränenpalast I wonder whether it really happened or whether I read it in a novel. The place is a snazzy visitor centre now, the bins full of cold beer long gone, the black walls and windows now, bright, sleek and gleaming.

With Berlin being a city where stories gather under every roof and on every street, a meshing of fact and fiction is perhaps inevitable. I think that night really happened, though, just another small Berlin story from its turbulent modern history.

“We know what we know,” reads the last line of Berlin Alexanderplatz, “we had to pay dearly enough for it.”

Or as an overawed idiot might have put it one cold Berlin night long ago: blimey.