Boris Johnson is not the only reason Boris Johnson is in deep trouble. Setting rules in the biggest national emergency since 1945, breaking them and lying about doing so are the cause of the immediate high drama. But even without the law-breaking and the mendacity, this government would be in trouble.

What do we see if Partygate is fleetingly cast aside as if it had not happened? Apart from the familiar Johnsonian chaos we do not see very much. This government and governing party, now in its fourth term, had run out of energy, purpose and discipline long before it had cause to worry about a law breaker occupying No 10.

All long-serving administrations fizzle out. Re-energising them is close to impossible. They carry with them a feeling of the last days of Rome.

The original driving objective of Johnson’s government was Brexit. Currently the only animated focus is an attempt to renegotiate the deal with the EU that Johnson had hailed as a triumph. Meanwhile, a fragile economy totters partly because of his chosen Brexit. Elsewhere the journalist prime minister delivers headlines about sending foreigners off to Rwanda, selling off housing association property, “levelling up”, and a “historic social care plan” along with the rest of the “world-beating” slogans that are placed on the front pages by supportive newspapers. Once Johnson has made a speech announcing a new plan, he moves on. He has written that column and it is time for the next one. None of the initiatives have been thought through beyond their immediate attention-grabbing impact.

A levelling-up white paper offered no new investment. The tax rise to pay for social care is being spent largely on the NHS and the wider “plan” does not address the urgent issue of staff recruitment and standards in care homes. The housing association sell-off hails from David Cameron’s 2015 manifesto. Even Johnson’s climate-change mission lacks direction. Goals are set, but the means of achieving them are unclear. Only unforeseen emergencies give the government a spark. The nightmare in Ukraine allows Johnson to play Winston Churchill, his ultimate fantasy. Even so, this role comes courtesy of Putin and not as part of his agenda.

The wider shambolic vacuity is not explained solely by Johnson’s own indifference to detail, impatience with the long haul of policy implementation and tendency to pick weak colleagues who will not challenge him. There is another factor. Politics is a human endeavour. Governments become exhausted. Their MPs become more rebellious and less disciplined. There is a pattern here with long-serving governments and it highlights many lessons in reading the current situation.

Take the final years of the Conservative government that was elected in 1951 and continued in power until 1964. Even Harold Macmillan, a figure far more substantial and experienced than Johnson, struggled in the early 1960s to make any waves. His government became undermined by scandal and listlessness while Macmillan lost his mischievous zeal and fell ill. Ministers became ineffectual and the exhausted prime minister mishandled them.

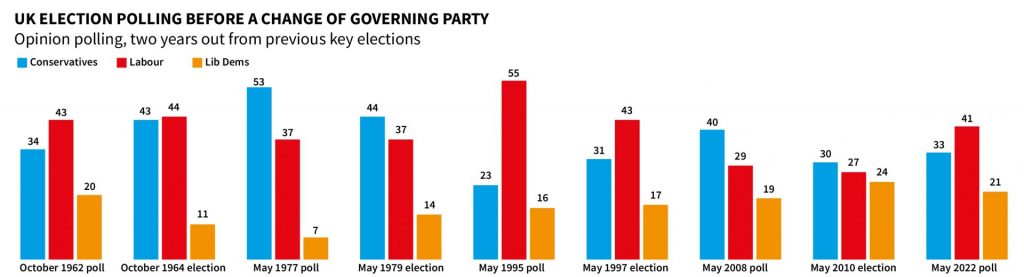

In the “night of the long knives” he sacked several ministers as part of the most brutal reshuffle in modern times. The move conveyed panic rather than renewal. The newish leader of the opposition, Harold Wilson, popped up to declare “I see the prime minister has sacked half his cabinet. The wrong half.” Voters and much of the media began to laugh with Wilson as he mocked Macmillan. Illness led to Macmillan’s resignation and triggered the brief reign of Alec Douglas Home, who did little to revive a beleaguered government. The momentum was with Labour.

Three decades later, John Major struggled with an ever greater sense of impotent despair. He came to office in 1990 after 11 years of Conservative rule and won an election in 1992, a considerable achievement. Major also seemed to have new ideas. He wanted Britain to be “at the heart of Europe”, he abolished the poll tax, a symbol of Margaret Thatcher’s reckless third term, he devised a “citizen’s charter” aimed at reviving public services. But his MPs had been part of a governing party for so long they became complacent and ill-disciplined, making Major’s life a form of hell.

The insurrectionary behaviour highlighted deep divisions within the Conservatives and the party fell behind in the polls. Sensing they were going to lose the next election, MPs lost interest in obeying the whips in the hope of a ministerial job. They assumed that pretty soon there would be no ministerial vacancies for their side. This became a self-fulfilling assumption as their behaviour made Major look even weaker and the party more divided.

Again Major was a far more weighty figure than Johnson, but as his former chancellor Norman Lamont observed during his resignation speech, the government was in office but not in power. In doing so Lamont highlighted another symptom of long-serving governments. Some cabinet ministers or former ministers become harder to control. They can see the end is in sight and that there is no overwhelming motive to keep in with a doomed prime minister.

This is what Gordon Brown discovered as he took over from Tony Blair in 2007 after the government had been in power for 10 years. The governing energy of 1997 had waned, some ministers were tricky rather than loyal and MPs, so keen to please after Labour’s first two election landslide victories, were less inclined to be loyal after a decade of power. James Purnell resigned suddenly from Brown’s cabinet. There was speculation that others would follow. Ministers and MPs plotted several attempted coups. They were keen for the foreign secretary, David Miliband, to take over. Miliband only half-shared their enthusiasm and did not act. This does not happen in a first term when the fresh excitement of government keeps all involved on their toes.

No wonder Brown was keen to replace Blair earlier, before the unavoidable dynamics of a knackered governing party began to take hold. Like Johnson in relation to Ukraine, Brown was energised by a sudden global crisis. The financial crash in 2008 gave him and his government renewed purpose. Brown was a more central figure in co-coordinating a global response to the crash than Johnson is now as Ukraine seeks to resist Putin, but his wider domestic agenda lacked energy and clear purpose, the same with all governments that have been in power for years.

Once again there is near-paralysis in Whitehall, irrespective of Partygate. Not much is happening as ministers, quite a lot of whom have been in office or close to office since the Conservatives were elected in 2010, struggle to make policy out of slogans. MPs are increasingly restless. Johnson’s many U-turns are performed partly because he cannot rely on the support of his backbenchers, in spite of winning a near-landslide in 2019. For a time after that election Johnson’s government felt as if it were a fresh administration and had nothing to do with the previous three terms of Conservative rule. But even a prime minister incomparably different to his predecessor, Theresa May, cannot transcend a law of politics. Parties that rule for several terms tend to lose the art of governing.

Even Johnson might have struggled less if he had been leading a government in its first term, newly elected after a period of opposition. His levelling-up agenda has considerable potential and Johnson might have had the authoritative will to overrule an ideologically inflexible chancellor such as Rishi Sunak. He might have been able to claim with a degree of credibility that he was leading a one-nation Conservative government, moving on from Thatcherism at last to face a world very different from the one that Thatcher had sought to navigate in the 1980s. First-term governments seem fresh and exciting for a time.

Instead, now, there is a mood of bewildered decline. If Johnson falls, a successor will struggle to re-energise the government and win a fifth successive term. Major managed to pull off the trick and win a fourth term in 1990, but his triumph was a prelude to five draining years of nightmarish decline. He could not win a fifth term in the same way that Douglas Home and Brown could not win a fourth term for their respective parties.

Revealingly, when Brown sought to form a coalition after the 2010 election, quite a few Labour ministers publicly argued that they should take a bow and return to opposition. That was partly because the parliamentary arithmetic was not on their side, but they were also exhausted. Their hunger for power had been sated. If they had not served for three terms they would have been up for government whatever the unpromising composition of seats in the Commons.

As I write, the government is preparing to unveil its legislative programme for the coming parliamentary session. There will be more on levelling up, and perhaps the plan to contrive confrontation with Europe over the Northern Ireland Protocol will take legislative form. Education and the NHS may get a look in. Do not expect much in any of these areas beyond the headlines.

Because England tends to elect Conservative governments, an impression is easily formed of near one-party rule. But even England’s ruling party of choice needs a break to ask what it is for and what the policies are that make sense of a newly defined purpose. The questions are being posed now as ministers and Tory MPs wonder, restlessly, what is going to happen next. What are the policies that reflect our values once we can agree what our values are? How do we retain the support of our electoral coalition bound by enthusiasm for Brexit and little else? That is what happens to governments that have been in power for a long time. They begin with energetic verve and end with exhausted ministers and MPs wondering not only about who should lead them but what they are for.

Steve Richards’ live show Rock n Roll Politics returns to Kings Place on June 8. His latest book is The Prime Ministers We Never Had: Success and Failure From Butler to Corbyn