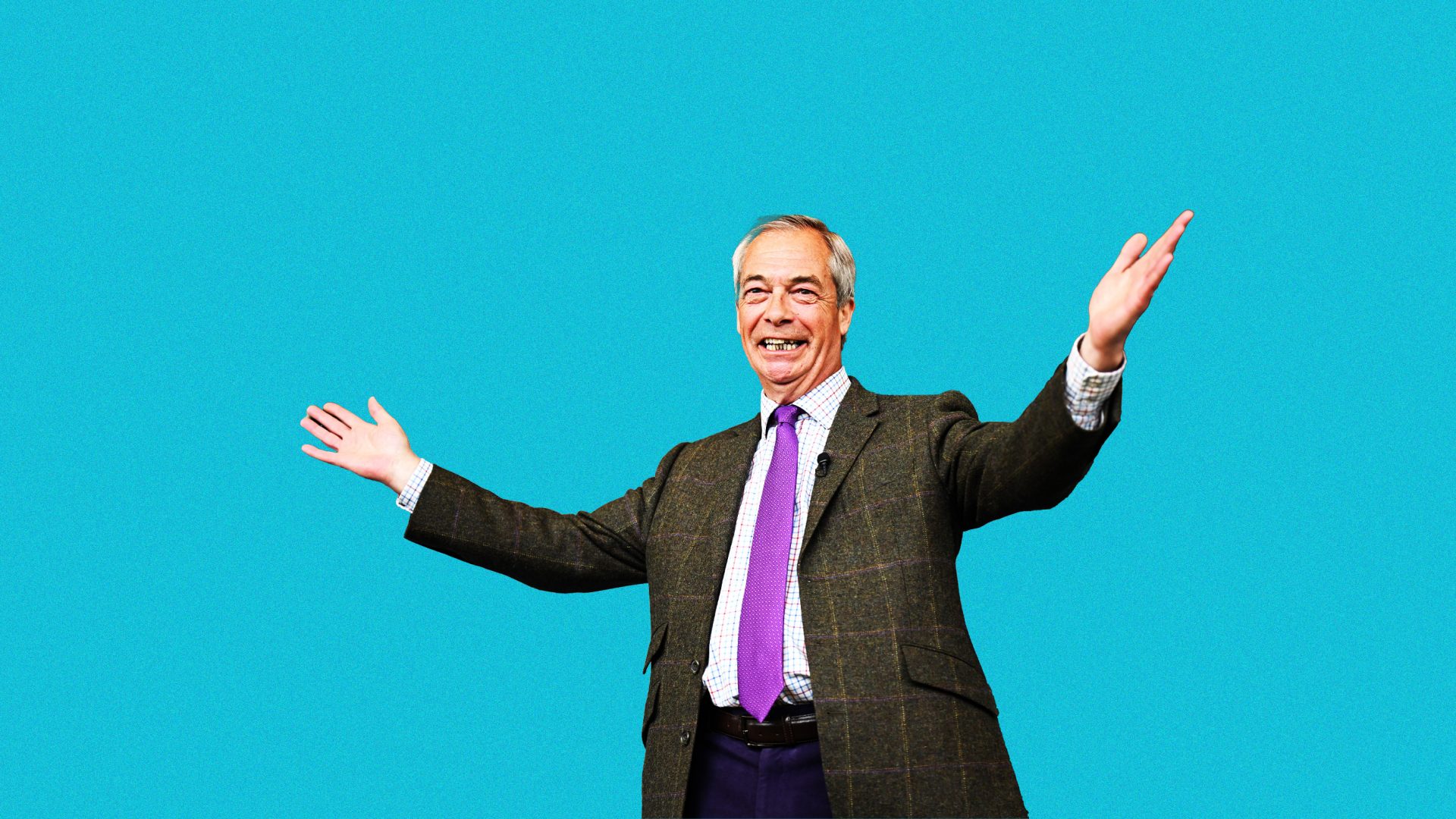

Amid the various international crises, a political earthquake is about to erupt closer to home. If the opinion polls are even close to being correct, Nigel Farage and Reform are going to perform spectacularly well in the UK local elections on May 1.

In contrast, the Conservatives risk losing 500 seats in what one Tory strategist described to me as a “meltdown”. Labour is not confident about winning the Runcorn by-election held on the same day, in a relatively safe seat. Inevitably, the threat comes from Reform.

Most local elections come and go. They are of fleeting national significance. These are different. Not only are they the first big electoral test since the general election, but they may well lead to Reform wielding power in some councils, and perhaps at a mayoral level, too.

Several local authorities are likely to emerge with no party in overall control, which means the other parties, specifically the Tories, may have to do deals with Reform in order to run their councils. This is a huge speedy leap for Farage’s party.

READ MORE: The hard right will tear itself apart

Reform was in the doldrums until its leader returned to the helm at the start of last year’s general election. Now it has a handful of MPs at Westminster and looks as if it is the party with intoxicating momentum, on the verge of wielding power at a local level, and terrifying the two bigger parties nationally.

There will be glorious consequences for Farage. Some mighty newspapers will swoon. The fearful BBC will not be able to contain its excitement. Tim Montgomerie tells me he got more than 100 requests from BBC outlets to do interviews after his defection from the Conservatives to Reform at the end of last year.

Terrified of the right and eager to follow what appears to be political fashion, nervy BBC editors will be keener than ever to invite Reform representatives on to their programmes for months and years to come. Although they will go over the top, they will have some cause for their offer of a political stage if Reform appears to be the coming party.

Meanwhile, the leaderships of the Conservative and Labour parties pay the ultimate homage, becoming obsessed with the threat posed by Farage. Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, tells the prime minister what to say and think on most domestic issues. Much of his advice is shaped through the prism of Reform and the threat to Labour seats.

Would the government have called an emergency sitting in the Commons during the Easter recess seeking permission to take control of British Steel had Farage not backed the policy first? At the very least, No 10 will have calculated the electoral consequences of letting the Scunthorpe steel plant close while Farage was putting the “patriotic case” for public ownership.

Fear of Farage is also a factor in McSweeney/Starmer’s continuing caution over Brexit. Farage leads a party that won five seats at the election, and yet a landslide government feels the need to take his views into account in some of the biggest policy areas.

But this is nothing compared with the impact Farage is having on the Conservatives, a party unused to facing an alternative vehicle seeking to replace it. Should they do a deal with Farage? Should they replace Kemi Badenoch with Robert Jenrick, a figure who has metamorphosed into a Farage-like character?

After a slaughter at the general election, the Conservatives were always going to struggle to decide who they are or should be as a political force. Farage makes the identity crisis much more problematic and deeper still.

Once more it is Farage who makes waves. He did it with Ukip when it attracted defectors from the Conservatives and attracted the highest number of votes in the 2014 elections for the European Parliament. More storms built up around British politics when Farage formed the Brexit Party, topping the poll in the 2019 European elections, triggering the departure of Theresa May. Now, here we are again with Reform.

But step back from the current impact of Farage and note the pattern. This is indeed the third party that he has led in a way that has caused wild disruption. That is a tribute to his genius for spotting a gap and filling it with audacious verve. The sequence also reveals the limits of Farage as a player of party politics.

Setting up parties is much easier than the hard grind of sustaining them. When the going gets tough, Farage gets going.

He resigned as leader of Ukip the day after the Brexit referendum. He was not up for the hell of the Brexit negotiations that were a consequence of his victory, in which he could have played a role from outside parliament as Ukip leader. Instead, Farage chose the relative comfort of the LBC studio, where he was an excellent presenter.

Once Britain had formally left the EU after the 2019 election, the embryonic Brexit Party was no more. He looked on at the twists and turns of Brexit from an even better-paid role as a presenter on GB News.

Now he has no choice but to stay the course, to face the consequences of his success with Reform. This is where politics becomes tricky.

At some point, a new party must develop policies based on clearly defined values. Before then, the team that will decide those polices must be appointed.

Its relationship with the membership is central. How much power should members have in deciding policies? That question has tormented Labour leaders since the party’s inception. A leader must manage a team in parliament and several teams outside. The wider strategic positioning must be agreed.

In Reform’s case that is a big issue. Does Reform seek to replace the Conservative Party or work with it? How best to attract Labour voters as well as disillusioned Tories?

Watching Farage and Reform flourish in what will be an ecstatic year for them, I am reminded of the SDP, the party that triumphed fleetingly after it was formed in 1981. At first, the SDP made at least the impact that Reform is having now. It topped the opinion polls for months.

A survey in September 1981 placed the SDP in first place and the Conservatives in third. The front-page headline in the Times was “Thatcher – the most unpopular prime minister of the 20th century”.

The SDP won by-elections and, in alliance with David Steel’s Liberals, spoke of forming the next government. They were “breaking the mould” of British politics.

Then the hard grind kicked in. The SDP wanted to replace Labour and to be an alternative to the Tories. Yet although in huge difficulty, the Labour Party refused to die. Meanwhile, there were differences over policy and relations with the Liberals.

In the 1983 election, Thatcher won a landslide and the SDP were miles behind Labour in terms of seats, though much closer on the basis of votes cast. This was the bleak fate of a new party set up by former cabinet ministers who were used to the nightmares of compromises, dashed hopes and unfulfilled ambition demanded by party politics.

Farage is closer to a presidential figure working in a party-based system. He has never been that bothered about the contents of his various parties’ manifestos or even what was on his own personal website.

When questioned about eccentric or contentious policies in the past, he has dismissed them as irrelevant or no longer applicable. Now he is seeking power more directly he can no longer be so casual.

Yet so far he is not even at first base in agreeing the party’s values. Evidently, the MP Rupert Lowe had different ideas to Farage and has been suspended.

At some point, policies must follow. Where precisely does Reform stand on “tax and spend”, Britain’s place in the world, the role of the state, levelling up poorer areas where Reform has a strong constituency? What about social care?

The other parties agonise over these questions as an election approaches. Reform will have to do so as well. But policy detail is not an interest of Farage’s.

He is a supreme reader of the political tides and finds the ebb and flow endlessly fascinating. He is the best communicator among current leaders. Yet he will struggle working with others to settle highly charged policy and strategic questions in a way that is coherent, credible and retains the widest possible electoral appeal.

Perhaps none of this matters any more. Maybe next month’s triumphs clear a path towards government for Farage and Reform. Possibly if angry voters are asked to join “the people’s revolt” they will do so without asking further questions. Disillusionment with the other parties and a charismatic leader is all that is required.

I doubt it. For a start, there will always be a Conservative Party. England’s governing party of choice is not going to disappear, just as the Labour Party did not in the 1980s.

Managing a party and policy programmes reveal much about competence or incompetence. Voters follow little but tend to reject from a party if they sense chaos or a policy pitch that falls away on closer examination.

Farage and Reform will hugely enjoy the next few months. But he cannot then set up a new party and have even more fun. He is stuck with Reform, and by midterm in this strange parliament, the going will get much harder.

Steve Richards presents Rock N Roll Politics live at Kings Place, London on May 8. He is the host of the Rock N Roll Politics podcast