I begin with a confession. Usually, I am not a fan of articles that choose the “worst” prime minister or indeed the “best”. The assertion is too sweeping and the judgments too predictable, wholly dependent on the choice of author. In the case of Boris Johnson, I make a willing and urgently necessary exception.

The urgency arises from a mythology already taking shape around the departing prime minister. As part of the madness we are all living through, polls of Conservative Party members suggest that if Johnson’s name were on the ballot paper he would win the current leadership contest with ease. To the members, he is the martyred prime minister, forced out early by the traitorous Rishi Sunak. For them, he got the “big calls” right.

The perception of the unfairly toppled titan is fuelled by Conservative-supporting newspapers that continue to report his final days as if he were a mighty emperor bestowing his genius on a grateful nation. This is the essence of their reporting when he is on holiday in Greece or having a party at Chequers.

More dangerously, this absurd narrative, the betrayal of greatness, is shared by Johnson. One of his heroes is the mythological version of Churchill, the war leader who endured many lows as well as soaring highs during his political career. A part of Johnson dares to calculate that another Churchillian high is around the corner for him if he keeps going.

His immediate future is always what matters. One of the ways Johnson is able to move on from the chaos around him is his wilfully selective memory. In this case, he forgets conveniently that he could not form a government before he resigned. Potential ministers refused to serve. They walked away because even this group of subservient mediocrities, willing to accept humiliation after humiliation in order to keep their place in Johnson’s administration, could continue no further.

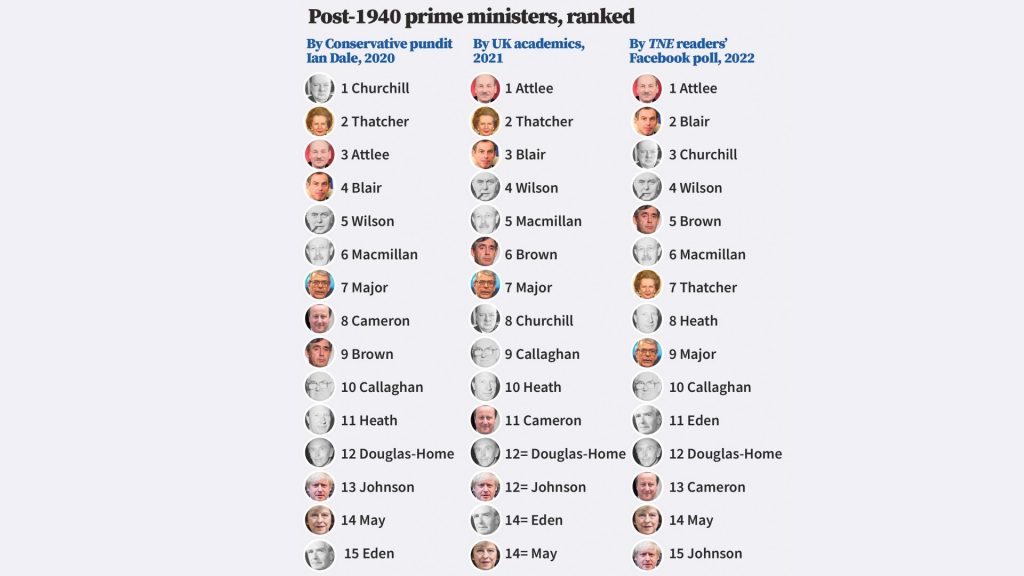

Belatedly they made the right call. I have no doubt that whatever the frenzied verdicts of Tory members and newspaper editors, historians across the political spectrum will judge Johnson’s premiership to have been a calamity. For all my wider reservations out the claim, I judge him without qualification to be the worst prime minister in the UK’s history, the least suited for office and one who was predictably unable to adapt and change to the demands.

The main reason he wins this unsought-for prize is his persistent, casual frivolity. For him the UK was a great big Etonian playing field in which he could strut and posture, glorying in reaching the historic heights of being prime minister.

His fellow Etonian, David Cameron, runs him close in regarding politics as a game. Cameron was also fascinated most by the tactical questions, how to win, how to keep power, how to pretend to be what he was not. But Johnson took the game-playing to another league during a period of seismic change when the country he ruled was already fragile. He leaves it in a far more precarious state. The UK is at its most dysfunctional and economically weak since 1945.

Johnson’s leadership is not the only cause, but it is a major factor. His conduct in relation to Brexit, a defining mission for him, remains as mind-boggling as it is overlooked. The entire sequence is part of a much wider dark pattern. According to Dominic Cummings, admittedly another subjective narrator, Johnson had no idea how the Customs Union worked as he instructed his weird courtier, Lord “Frosty” Frost, to negotiate the hardest possible Brexit. As Johnson told Frost vaguely what to say and do during those calamitous negotiations there is no evidence that he had thought through any of the consequences.

He was never interested in consequences. As a result ,the future of Northern Ireland is in nerve-shredding doubt. As ever, Johnson took the easy route, lying to business leaders in Belfast that there would be no additional paperwork as a result of his “deal”.

Companies now creak under the burden of the paperwork required to access the single market on their doorsteps. Queues at Dover and other points of theoretical departure from the UK are insanely long. Businesses tell the governor of the Bank of England that in a competitive field labour shortages are their biggest worry. Consequences.

In an emblematic exchange, Johnson told the president of the NFU, Minette Batters, that he would “rather die” than hurt the UK’s farmers. Days later, he hailed a trade deal with New Zealand that will kill off many farmers as they struggle already with the consequences of his Brexit. Batters wonders whether he lied to her, believed what he said at the time or had no idea what the trade deal would mean. Probably all three were part of the damning explanation. All was wacky under Johnson. Theresa May’s Brexit deal was scrutinised around the clock for months, in cabinet, in the House of Commons, leading BBC news bulletins and newspaper front pages. Ministers resigned, pundits were in demand to pontificate, the Labour Party thought of little else. Her deal was never implemented.

Johnson’s deal was scrutinised by nobody and took legislative form after a day’s debate in the Commons. Some of those who worked in No 10 at the time tell me they doubt if Johnson read the full deal negotiated by the hopeless Frost. His historic economy-wrecking deal was almost certainly not even scrutinised by Johnson. The frivolity combined with an instinctive mendacity applied from Day One. Outside No 10 on the day he became prime minister, he declared that he had a plan for social care. There was no plan. There is still no plan.

As the pandemic raged across Europe and headed towards the UK, he delivered a lofty speech in Greenwich mocking other countries for closing down to protect their populations. He proclaimed that the post-Brexit UK had no intention of shutting down anything, an adolescent thought process that delayed lockdown and killed many. His subsequent retreat to Chequers soon after that fantastical speech, not bothering to attend vital Cobra meetings, would have led to screams from the newspapers for the resignation of any Labour prime minister.

The pattern continued inevitably post-pandemic. The list is endless, his attempt to change the rules governing MPs on the basis of one column written by his friend, Charles Moore, the parties, the lying about the parties, the furniture in No 10, the honours to friends, donors and powerful editors. Then there was the vacuous emptiness of “levelling up”, promising much to those who need more active government and not bothering to deliver. He was indifferent to the hard, unglamorous grind of policy details and implementation.

Now there is the weird final phase. Most prime ministers removed from power are traumatised immediately. Some visibly shrink in response to their distress. Johnson has never looked more content. As the UK economy teeters on the cliff’s edge, he has enjoyed two holidays and parties at Chequers and at a donor’s mansion. He spends most of the time at Chequers enjoying himself. This is what he thought being prime minister was all about, a glorious political stage without responsibility.

The fear of scrutiny in any form stands out. Cameron was almost as frivolous, but he was exposed to scrutiny and managed the layers of accountability with aplomb, Liberal Democrats in his cabinet, the different wings of the Conservative Party in his government. Lloyd George was almost as dodgy as Johnson in abusing prime ministerial powers, but he was one of the most substantial and visionary policymakers of the 20th century.

Other prime ministers failed to deliver domestic reforms in the way that they had hoped. Anthony Eden, James Callaghan, Gordon Brown and Theresa May were diverted and ruled briefly. They were all big figures before they got to No 10, and in the case of Brown, responded to the 2008 global crash with epic focus. No one can accuse those four of an indifference to detail or lacking integrity.

Callaghan and May ruled with no majority for most of their leadership. Johnson had a near-landslide. Going further back, Neville Chamberlain is widely condemned for his “appeasement” of Hitler in the 1930s, but he appeased for substantial reasons even if he was wrong.

What do potential prime ministers reflect on when they make their moves to the very top? Most have observed closely serving prime ministers and have some sense of the pressures, responsibilities and level of scrutiny. A few have thought through plans for the country that they seek to implement. Some succeed in doing so: a factor that tends to see Clement Attlee and Margaret Thatcher battle it out for “best prime minister”, wherever we stand on the policies that were implemented in ways that changed the UK beyond recognition.

Johnson was different. He thought of Churchill, the mythologised version that arose from his biography of the war leader. Probably he reflected on Pericles and Cicero, along with other Greek heroes from the safely distant past. No doubt he thought about “beating” Cameron’s record by winning big at an election.

There is no evidence that he had any sense of what was required to revive a divided, battered country. He has been the worst so far. Yet as part of the dire legacy, his successor might prove to be even worse.

Steve Richards presents Rock n Roll Politics: The Start of the Liz Truss Era at Kings Place, London on September 19