Conservative prime ministers come and go with such crazy speed their resignation speeches outside No 10 are soon forgotten. Within a nanosecond we move on to the next prime minister and his or her agenda. Liz Truss is freakish history. Rishi Sunak is the new king.

Yet it is worth reflecting for a moment or two on the words of Truss as she took her pathetic prime ministerial bow. With an unapologetic flourish, she declared that “we set out a vision for a low-tax, high-growth economy that would take advantage of the freedoms of Brexit”. Here was her one final attempt to justify her calamitous, economy-wrecking mini-budget. She was seeking to make sense of Brexit.

In doing so she becomes the latest prime minister to have risen and fallen over the ill-defined fantasy of Brexit. Truss became a favourite with party members when she was trade secretary, hailing her puny post-Brexit trade deals as if they were alone going to propel the UK to the promised land. As prime minister, she and her allies framed an economic policy that was based on their post-Brexit vision.

Leaving the EU was their route to a low-tax, small-state economy. Truss had been a Remainer but joined her friends in the Taxpayers’ Alliance and the Institute of Economic Affairs with the passion of a defiant convert.

The entire sequence was another Brexit dreamland. Truss’s trade deals were based on those negotiated by the EU, and in some cases were worse for the UK in as far as they made much difference at all. Her plan for a post-Brexit UK as outlined in the mini-budget imploded within hours of delivery. Sunak had warned her of the implosion, but as a committed Brexiteer, he now faces the consequences without any plan to deal with them.

Even the soap opera of Truss’s final few days was shaped by Brexit. In order to secure growth, Truss realised the UK needed more immigrants. Recently the governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, declared that labour shortages were the top of businesses’ concerns, much more so than worries about tax levels. But she had appointed as her home secretary Suella Braverman, a reactionary shallow populist who regarded her post-Brexit responsibility as “protecting the borders” from beastly foreigners who might want to fill some of the crippling vacancies.

In her final act of prime ministerial assertiveness, Truss in effect sacked Braverman. The sacking heightened the sense of a government falling apart. Once again, Brexit hovered over the chaos. It is far from clear that Sunak has a politically feasible alternative to post-Brexit labour shortages.

Brexit does more than hover. It is the fundamental cause of the turbulence that has led to the fall of three Conservative prime ministers since 2016. David Cameron resigned after losing his foolish Brexit referendum that he did not need to hold. Theresa May went next after failing to get her Brexit deal through the Commons and with her MPs in almost joyful insurrection. Brexit explained the initial rise of Boris Johnson to the leadership. He resigned as foreign secretary over May’s deal and became prime minister in July 2019 pledging to leave the EU “come what may” by the end of that October. He had no idea how he would meet that pledge and characteristically did not do so. Instead he won a general election promising to “get Brexit done”.

Unsurprisingly, Brexit is still far from done. With great delusional reluctance, Johnson was forced out of No 10 in July as he was incapable of forming a government.

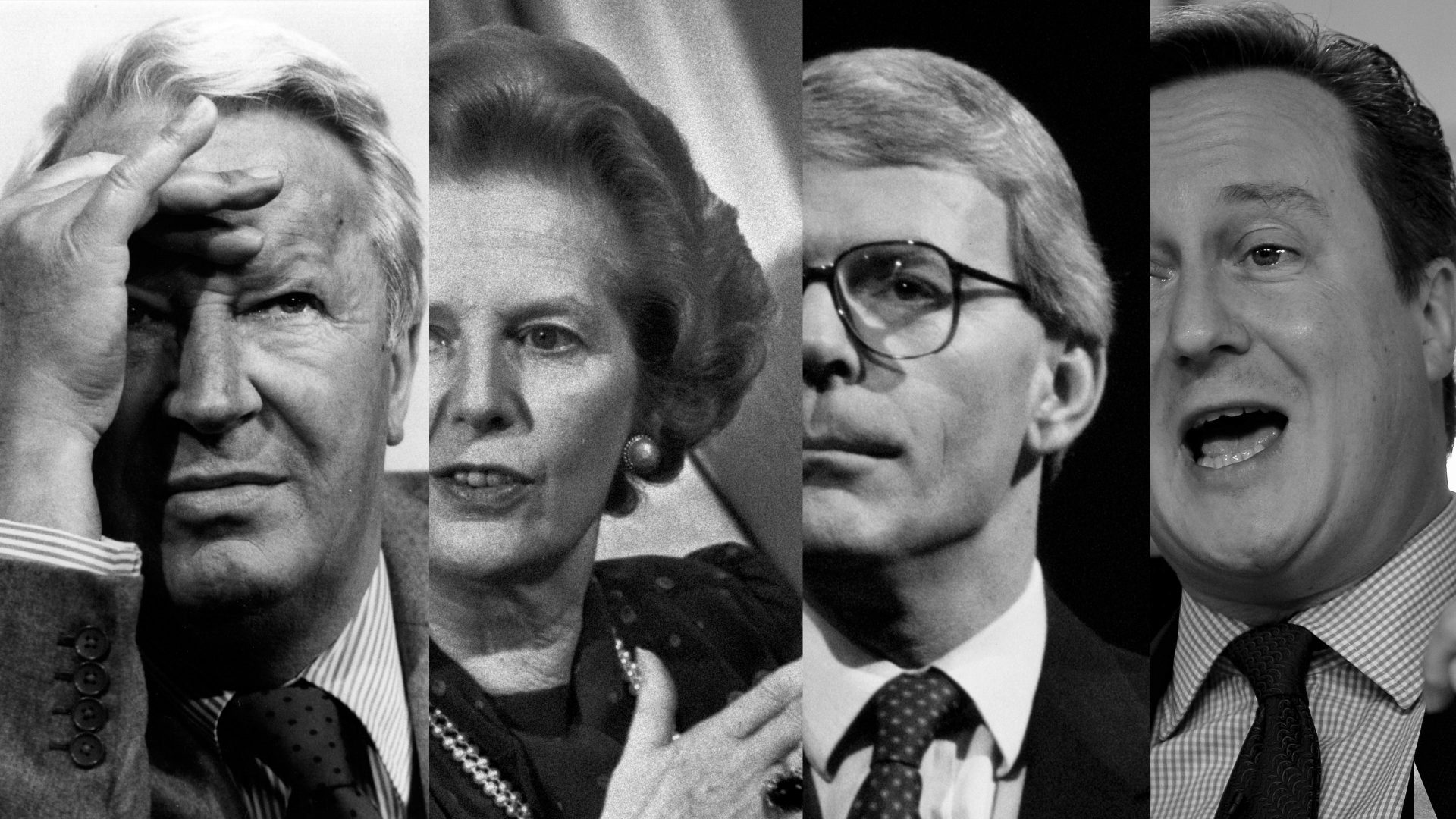

What is striking is that the four Tory prime ministers to have fallen since 2010 have left office between general elections. Not one of them has departed as a result of losing a general election. This pattern is revealing. The four previous Conservative prime ministers have found it relatively easy to win elections from 2010 onwards and then impossible to lead their parties.

Once again Brexit is the factor. Cameron won an election by a small margin in 2015 pledging a referendum on EU membership, thereby stifling the threat posed by Nigel Farage and Ukip. May won most seats in 2017, insisting that “Brexit means Brexit” and she would deliver. Johnson won a near-landslide because of his similar pledge to get the UK out of the EU. In each case, Labour was placed on the defensive, not knowing quite what to say once the referendum had taken place.

But while Brexit has been an asset for Conservative prime ministers at general elections, it has tormented them when they seek to lead their party and govern the UK. This is largely because Europe as an issue has transformed the parliamentary party, making it far more rebellious and insurrectionist. The mood changed in the 1990s when Conservative MPs made John Major’s life hell over the Maastricht Treaty. At one point Major had to call a vote of confidence in his government in order to get the Maastricht legislation passed. At another, he resigned as party leader while remaining as prime minister in order to stage a leadership contest.

He won the contest, but the need to hold it shows how rebellious Conservative MPs had become. Already they were forming a view about Europe, sovereignty and the potential might of the UK distanced from the EU.

Equally importantly, they were enjoying themselves. Loyalty had been the Conservative Party’s secret weapon, but being disloyal was much more fun. I recall bumping into a couple of the regular rebels in different BBC studios on the same morning in the mid-1990s. One of them said to me, “We’re available to perform anywhere, the Today Programme, the World at One, Barmitzvahs, children’s parties.” She was only half-joking. Ominously for Sunak, on the day he became Conservative leader the European Reform Group could not agree whether or not to endorse him.

Ever since the stormy 1990s, a significant number of Conservative MPs have put their ideological view about the UK and Europe above any support for a prime minister. As a result, Tory prime ministers have lacked authority over their parliamentary party. They have had to twist and turn in an attempt to keep them onside.

There is an added twist. The unleadable MPs have selected leaders without many qualifications for leadership. The shallow Cameron was too easily biddable when he met his Eurosceptic MPs. May lacked the charm and guile to outmanoeuvre her resolute insurrectionists. Johnson’s leadership was so chaotic that some of those who worked with him doubt if he has ever read in full the calamitous Brexit trade deal negotiated haphazardly by the preposterous Lord Frosty Frost. We know about Truss.

As Brexit has failed to deliver any of the Brexiteers’ vague dreams, they have become even harder to control. Instead they look around to blame anyone but themselves. The former Brexit secretary, David Davis, complained of a “Remainers’ Brexit” even though it had been negotiated by Frost, a hardline Brexiteer. Others blame the EU for not allowing the UK to have its cake and eat it. Quite a lot blame whoever is prime minister at any given time.

Blaming others allows them to continue dreaming without evidence on their side, part of the wider Brexit culture in which experts are cast aside. The culture reached a climax with the fleeting Truss era when the permanent secretary at the Treasury was sacked, the Bank of England briefed against and the Office For Budget Responsibility briefly cast aside. This was all done with a self-confident swagger.

There is a more fundamental reason why the post-Brexit prime ministers have failed to make their mark. They need the sluggish economy to grow in order to achieve their other goals. As Truss put it, she wanted “growth, growth, growth”. Sunak needs the economy to grow, too, if he is to have a chance of winning an election. Brexit is the biggest obstacle, as the government’s own forecasts acknowledged when they analysed the impact of Johnson/Frost’s Brexit deal. When challenged on this Frost argued that Brexit was not about economic growth but securing “freedom”, the most ubiquitous and imprecise term in British politics.

One of the more surreal elements of this phase of long Conservative rule is that the various wobbly prime ministers and fleeting chancellors blame Covid, Vladimir Putin and even the Labour Party for the state of the economy. They cannot come to terms with the impact of Brexit, what it was about, what it has become.

Until a prime minister dares to start an honest debate about the dire consequences of Brexit others will fall too, as they seek to make sense of the Northern Ireland Protocol as well as all the constraints that limit access to the vast single market on its doorstep. Europe has changed the Conservative Party and made it impossible to lead. At some point, the party will need to change again by reflecting honestly and deeply about Brexit’s consequences. Until it does so the succession of tormented, short-serving Conservative leaders is likely to get longer still.

Steve Richards’ latest book is The Prime Ministers We Never Had; Success and Failure From Butler to Corbyn