In one of his final acts, the late Pope Francis declared Antoni Gaudí “venerable”, which is a precursor to sainthood. Gaudí, the architect of the great, tantalisingly incomplete Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, is on the path to canonisation, after living very much as Flaubert advised artistic types: “Be regular and orderly in your life so that you may be violent and original in your work”.

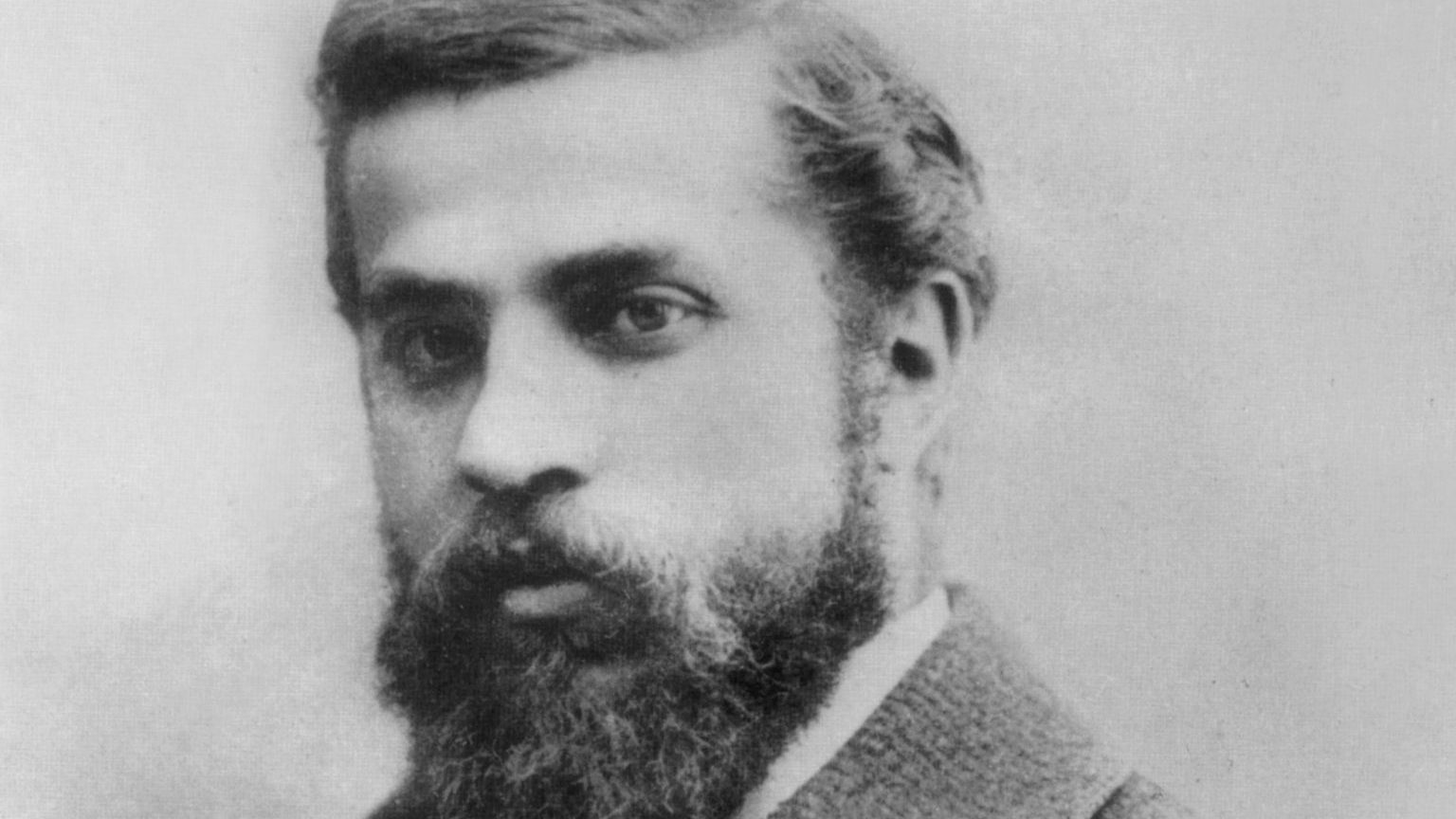

The man known as “God’s Architect” was born in 1852 into a family of artisans. He worked on his outlandish but godly project in Barcelona from 1883 until his death 43 years later, creating a kind of vaulting, psychedelic teepee. He never married (some believe he died a virgin) and followed a regime of unsparing asceticism.

He was “the hermit in the cave of making, a character out of Dostoevsky”, according to the critic Robert Hughes. “He did not go out in society. He could be glimpsed on the street, stoop shouldered, timid, white haired and blue eyed, dressed invariably in a baggy dark suit and slippers, munching on an orange or dry crust of bread as he shuffled along. One did not speak to him.”

The colour of his eyes was not an insignificant detail of Gaudí’s profile. A Barcelona bookseller and worthy, Josep Maria Bocabella i Verdaguer, was a leading light of a group of conservative Catholics who venerated Joseph, Mary and the infant Jesus. They were known as the Josephines. At a time of great turbulence for the church, with the Pope confined to Vatican City by Garibaldi’s victory in Italy, the Josephines planned to raise a place of worship in Catalonia as a rallying point for the faithful. It came to Bocabella in a dream that the man to build his edifice would have blue eyes.

Gaudí would go on to design swoon-makingly original mansions, parks and churches. But he was in his early 30s, with little to show on his resume, when he won the confidence of the bookseller with his intense and orthodox faith. The architect vowed to build “a palace of Christian memory”, as Hughes puts it, in which every niche and tower would represent an aspect of dogma or an event from the New Testament. It would be like a book made from stone, in which the entire iconography of Catholicism could be read.

Bishops and cardinals who were invited to check on the progress of the Sagrada Familia were apparently reassured by Gaudí’s vision, though they may well have been consternated by his methods, which looked to the untrained eye to be evidence of a pagan animist cult. He had turkeys anaesthetised so he could make plaster casts of them and see how they’d look in his friezes. He even had a braying donkey winched up the side of the building as he wrestled with perspective in creating his nativity.

With its aerial bestiary and the soaring chicken drumsticks of its spires, it’s hardly surprising that the Sagrada Familia was admired by Salvador Dali and his fellow Surrealists. It seemed to have a different resonance to the hippies in the Sixties, materialising like a mirage out of an acid trip.

But Gaudí’s inspiration was more prosaic: long hours in a blacksmith’s forge watching his father tease sinuous shapes out of red-hot metal, and childhood walks in the Catalan countryside. “Nature is the Great Book, always open, that we should force ourselves to read,” he said.

Every form that an architect could possibly need had a prototype in the natural world: in animal bones and spreading tree canopies, in pinecones and the glittering armour of beetles. These were his pattern book. Astonishingly, Gaudí seldom drew his designs in advance. As for the few sketches which survived him, “They are drawings made by his assistants to understand what Gaudí wanted,” according to the Catalan historian Alexandre Cirici I Pellicer.

I first visited the Sagrada Familia more than thirty years ago and thought that it was what the first cathedral on Mars would look like. Dazzlingly light and eye-poppingly inventive, the nave and transept and apse were like the mansions of the architect’s mind, with whizzing curlicues representing his rapidly-firing synapses.

The place was just as he had left it, as though he’d brushed off the masonry dust and gone home to his comfortless apartment for a rare siesta. In fact, he hadn’t set foot across the threshold for almost seventy years, not since he was killed by a tram in 1926 when he was 74 (and still hard at work).

Like one of Gaudí’s stone fowl, the monument was petrified, frozen at the precise moment when the one man who could complete it was no longer available to do so. Part of the enchantment of the Sagrada Familia lies in the endless postponement of its topping-out ceremony. Gaudí’s work was the masterpiece that could never be flawed because it would never reach an end, as beguiling in its way as an unfinished symphony or half of a deathbed novel by a great author.

At a time when you can laser-print almost anything in your own home – provided your in-house AI doesn’t beat you to it, that is – there’s something deeply appealing in the grand project that will still be under way long after you’re gone. It’s like the church organ in Germany which has been playing a composition by John Cage for the past 24 years, and is not due to sound the last note before the year 2640 (a chord change is due next year).

Papal sleuths are investigating a miracle attributed to Gaudí: a woman was reportedly cured of a severe eye complaint after praying to the late architect. He will need another one to qualify for sainthood. But not even he can keep the rain out of the Sagrada Familia. The great imponderable of what his basilica would have looked like is all very well, but left to itself, it would eventually fall to ruin.

By 2011, one of Gaudí’s successors had accomplished what he failed to do and put a roof on it. I followed the sure-footed Jordi Bonet, then 86, as we scaled the breezy and vertiginous summit. He had been chief architect for 30 years, the eighth to hold the position, another man who had grown old in the job. He promised that work would finally be over by 2026, the centenary of Gaudí’s death. That remains the official forecast.

Amid the scaffolding and the steeples, Bonet told me, “I will not finish it, but others will finish in the future.” Bonet died in 2022. Like Vatican officials weighing up the merits of prospective saints, architects at the Sagrada Familia are accustomed to playing the long game.