His name was John and he wore glasses with lenses so thick that if you stuck one on the end of an old Smarties tube you could have looked through it and seen the Horsehead Nebula. His hair was so dense and uncontrollable that he must have gone to a welder rather than a barber. The shirt cuffs protruding from his tweed sports jacket were not so much frayed as unravelled.

To most people, John was just our local branch librarian. To me as a kid, he was a keeper of dreams, a curator of magic and a guardian at the gates of wonder.

John didn’t say a lot, he’d just gruffly stamp the books I’d selected and hand them back to me, but sometimes there would be an approving nod or a slight raise of the eyebrows at my choices. Occasionally, if there was a new Asterix book in, or a Captain Cobwebb I hadn’t read, he’d place it wordlessly on the counter and tap the cover, having put it aside for my consideration.

There were other Johns up and down the country, going about their tasks with a kind of quiet heroism, but they are becoming increasingly rare. We should recognise and celebrate our Johns because they are under graver threat than ever.

I’ve written a lot in these pages about the importance of libraries and in particular the challenges they faced under the last government. Local authority staff do their best with eviscerated resources, while in places where libraries have been closed altogether, communities have rallied to keep them open on a voluntary basis.

Inevitably, however, the need to spread local authority funds ever more thinly means further staff redundancies are leaving brilliant, qualified librarians with nowhere to take their skills. In addition, more and more local authorities are seeking to bridge the gap between funding and amenities with automation. First they came for our supermarket checkout staff, now they’re coming for our librarians.

Instead of a human face at the desk, advising borrowers on what they might read next, chatting about their choices or even just lamenting the weather with someone who might find these interactions to be crucial bulwarks against loneliness and isolation, libraries across the country are installing scanners where librarians should be.

Instead of handing over books to an actual person, borrowers in many parts of Britain can now scan their choices like a supermarket meal deal. No advice, no guidance, no chats, just impersonal efficiency.

Last month Stockport Council introduced automated kiosks to their 13 libraries. Once users have accessed the premises by scanning their library card and entering a PIN they can waft their reading matter beneath a flickering red light until it goes blip. Sutton Council in Surrey introduced a similar scheme to their six libraries in April, while in Bradford, where self-service has been introduced to the city’s 10 libraries, boss Christine May assured critics that “some people just want to pick up a book and be in and out”.

Conversely, in Haringey, the local authority found that adopting the scheme “has the potential to reduce staffing by 40%” but would “not be proceeding” after consulting residents. A trial in two Croydon libraries produced the conclusion that “current trends indicate a strong preference from library users for face-to-face services from library staff”, noting also that the system excluded from the premises those without a library card and, crucially, under-16s who can only use the facilities if accompanied by an adult.

So, while the future of the librarian isn’t exactly rosy right now, there does at least appear to be hope of some kind of future. Which makes this a good time to celebrate those whose job – or, if you will, calling – is too often derided, undervalued, unfairly satirised and at the very least underappreciated. Without librarians there would be far fewer readers and far fewer writers, and what a dull world that would be.

Librarianship is one of the oldest recorded occupations (recorded, naturally, by librarians). Ptolemy’s Great Library of Alexandria was founded in 323BC as a repository for every item of Greek literature ever created. The names of some of its librarians have been handed down the centuries, with Demetrius, Zenodotus and Eratosthenes among the pioneers responsible for the filing and cataloguing of what was to them every piece of written work ever produced.

In 15th-century Europe the invention of the printing press increased the circulation of books, facilitating in turn the development of the library. A key figure in early European librarianship was John Dury, born in Edinburgh in 1596, a Calvinist who spent much of his life travelling Europe hoping to facilitate Protestant unity in divisive times, but who during the English interregnum following the execution of Charles I became a custodian of the former royal library.

As early as 1646 he emphasised the importance of a good librarian as “a factor and trader for helpes to learning, a treasurer to keep them and a dispenser to apply them to use, or to see them well used, or at least not abused”, and four years later published The Reformed Librarie-Keeper, in effect the first how-to guide for librarians.

Across the Channel, after the French revolution, librarians Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon and Joseph Van Praet were responsible for selecting, assembling and cataloguing the 300,000 volumes that would comprise the publicly owned Bibliothèque National de France. A French royal library had existed since the 14th century, but the revolution added the seized private libraries of aristocrats to the national collection, cherry-picked and presented to the people for their enervation and improvement.

Libraries in Britain flourished in the Victorian and Edwardian periods thanks in no small part to the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, responsible for the construction of 660 public libraries. Such increased capacity combined with the losses of the Great War opened up new employment opportunities for women, too. In 1920 there was an equal gender split among British librarians and by 1960 women made up 80% of library staff, a ratio that remains broadly the same today.

Librarians are intelligent, organised and helpful, and provide a service way beyond the shelving and issuing of books, yet despite gallant service and lightly worn expertise they have suffered more than most from stereotyping. In Frank Capra’s 1946 classic It’s a Wonderful Life, for example, when James Stewart’s George Bailey is shown what life would have been like in Bedford Falls had he never existed, he runs through a town no longer sleepy and conventional but brimming with gaudy excess.

When he tracks down his wife, Mary, played by Donna Reed, he finds his sparky, vivacious spouse not only timid and plain, all tweed, hair slides and unflattering spectacles, but because of his non-existence she has become – gasp – the town’s librarian.

Whether this image reflected the prevailing perception of librarians or acted as the catalyst, it’s stuck. In the opening scenes of the original 1984 Ghostbusters the heroes are summoned to the New York Public Library because a spectral librarian – elderly, bespectacled, humourless, hair in a bun – is disrupting the shelves and fiercely shushing anyone who comes close.

In Buffy the Vampire Slayer Anthony Head is Rupert Giles, a tweedy school librarian at Sunnydale High with a future-denying faith in the mustiness of books over technology because “the knowledge gained from a computer has no texture, no context. The getting of knowledge should be tangible. It should be… smelly.”

Librarians deserve better than this. While some undoubtedly conform to this stereotype, I’ll wager most librarians will have a tweed-free wardrobe, interests beyond the Dewey decimal system and are fun to hang out with. They can, after all, count among their ranks an impressive list of people with reputations beyond librarianship.

José Luis Borges, for example, served as director of the National Library of Argentina from 1955 until the return from exile of Juan Perón. “I always imagined paradise to be some kind of library,” he said, which sounds brilliant to me.

Lewis Carroll, Marcel Duchamp and Hector Berlioz could all boast “librarian” on their CVs, as could Giacomo Casanova, who spent the last dozen years of his eventful life as chief librarian at a Bohemian castle.

Not all popular culture renditions of librarians have been entirely negative. Prisons have proven fertile screen territory for positive representation as books offer mental escapes beyond the walls. In the HBO series The Wire, deep-thinking gang member D’Angelo Barksdale begins to find order and purpose when he joins a book group and commences working in the prison library.

In Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, Taystee Jefferson finds similar fulfilment, telling a fellow inmate to “make sure you reshelve this book in its proper place. We on Dewey decimal and shit in here. Don’t let me find no aquatic sports over in paranormal phenomena”, which may be the single greatest librarian quote in the history of popular culture.

In the 1999 film The Mummy, Rachel Weisz will have had librarians in the audience out of their seats and cheering when her gallant Evelyn Carnahan, librarian at the Cairo Museum of Antiquities, announced “I may not be an explorer or an adventurer or a treasure seeker or gunfighter. But I am proud of being a librarian.”

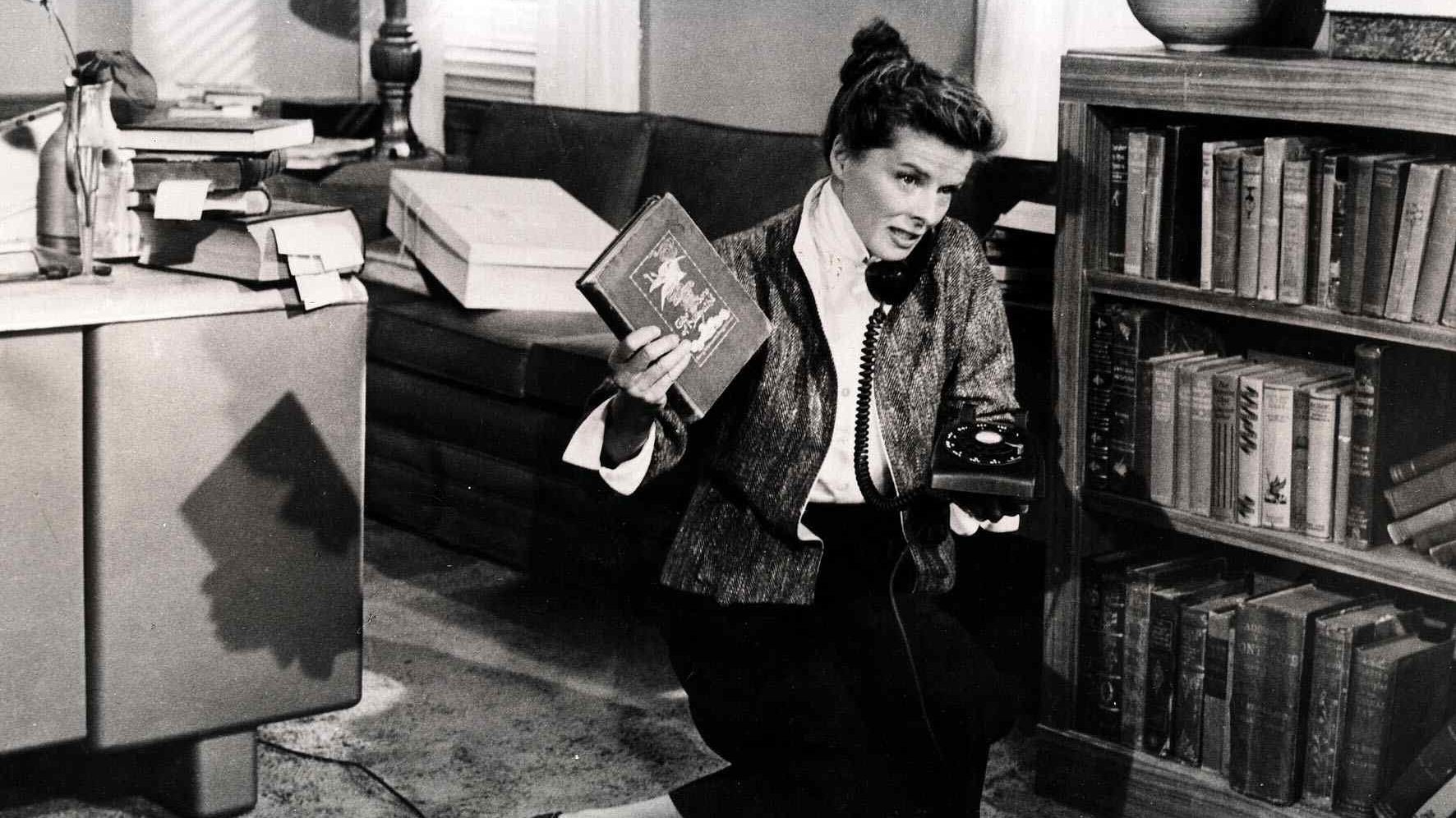

That’s a line of which Bunny Watson, arguably the greatest screen librarian of all, would have approved. Played by Katharine Hepburn in the 1957 film Desk Set, Bunny runs the reference library at a Manhattan-based television station – “I’ve read every New York newspaper backward and forward for the past 15 years, I don’t smoke, I only drink champagne when I’m lucky enough to get it, my hair is naturally natural, I live alone” – when Spencer Tracy’s Richard Sumner arrives to test a computerised system that Bunny suspects has been designed to make librarians obsolete.

Naturally, Bunny’s intelligence, sharp wit, experience and empathy for the nuanced, flawed, inspiring range of humanity that use library services triumphs over the cold, faceless logic of the giant computer and she and her staff are saved. Into the bargain she wins the heart of Richard Sumner with her all-round librarianness.

Desk Set is truly a parable for our library times. If automated kiosks help keep libraries open, that is unquestionably a good thing – but don’t let it be at the expense of qualified librarians.

After all, as John himself might have put it, despite the machines being programmed with Dewey decimal and shit, they’re not going to stop someone shelving aquatic sports over in paranormal phenomena.