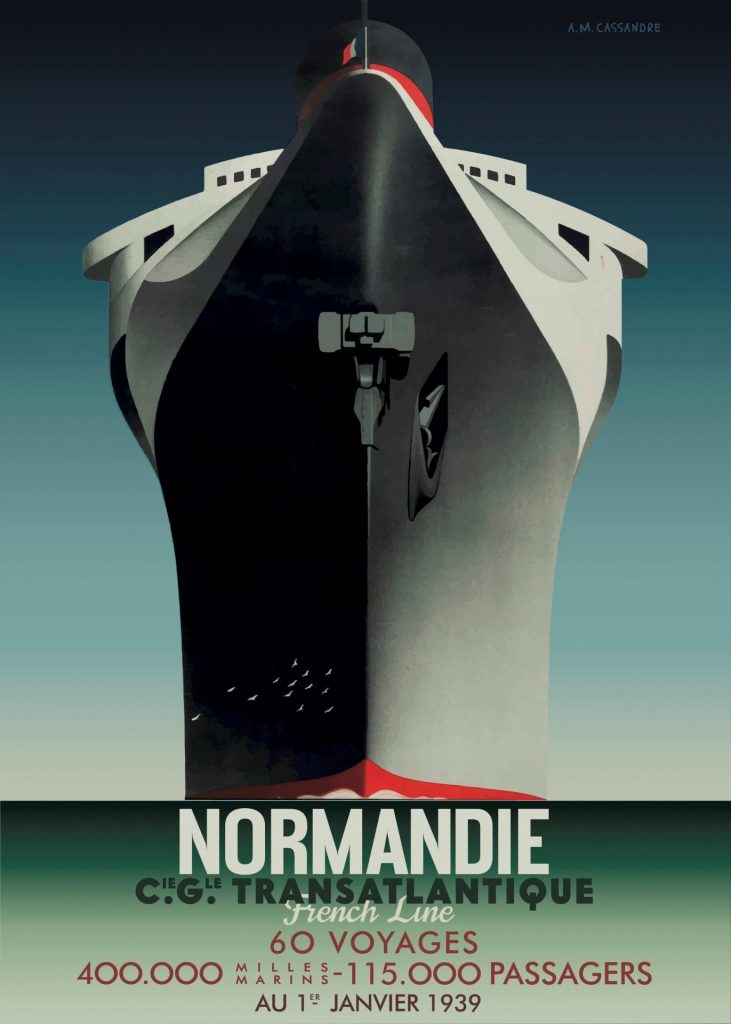

The SS Normandie was a real beauty – a classic, sleek ocean liner of nearly 60,000 tonnes, it was a creation of staggering art deco, jazz age opulence. The Normandie, built in Saint-Nazaire, was a floating encapsulation of French culture. Everything about it epitomised France – its style, its ease with luxury, its veneration of cuisine. And, like all French designer creations, it came with a hefty price tag. The Normandie cost $60m to build, and its construction was so entwined with French national prestige that the government put up most of the money.

In October 1932, 200,000 people came to watch the fastest ocean-going ship in the world being launched down the slipway into the Loire. But as it entered the water for the first time, the Normandie sent up a huge wave that engulfed a hundred spectators. None of them were seriously injured. But even so, it was a bad omen.

The interior of the SS Normandie was astounding. The first-class dining hall was more than 300 feet long. Passengers entered through a pair of doors 20 feet high, passing into a cavernous dining area lined with pillars of illuminated Lalique glass. There was a nightclub, an ancient Egypt-themed smoking room, a tennis court, kennels for travelling canines, winter gardens – including birds in cages, a theatre and even a chapel. The Normandie soon gained a reputation as the most opulent trans-Atlantic liner of them all.

She went into service in 1935, and soon set the record for the fastest-ever Atlantic crossing, while offering berths for a total of 1,972 passengers, 848 of those in first class. Each of the 400 first-class cabins had its own unique decoration, meaning that each one had its own design concept.

But war intervened, and in 1939 the Normandie was interned in New York, where the US authorities drew up plans to convert it into a troop ship, under the new name the USS Lafayette. But the conversion of such a complex and luxurious liner was a huge task, and by the start of 1942, it was still harboured in the docks of New York City, its military overhaul incomplete.

Then, disaster – on the afternoon of February 9, a fire broke out on board. The Normandie had been fitted with the latest fire-extinguishing systems, but they had been disconnected while it was in port and were not activated. When the New York City Fire Department arrived, they found their equipment was incompatible with the ship’s French systems. Strong winds drove the blaze through the Normandie, and soon its upper decks were all on fire.

Crowds of New Yorkers gathered at Pier 88 to watch the blaze. The port authorities and fire service hosed the ship down, eventually bringing the fire under control by 8pm that evening. But there was a problem – the fire boats that had pumped water from the port side had worked at a much faster rate than the fire brigade on the dockside, meaning that one side of the Normandie had taken on much more water than the other. The Normandie began to list dangerously to port. It eventually capsized, almost crushing a fire boat as it tipped on to its side.

A member of the port fire authority was killed in the blaze. Nearly 300 others were treated for smoke inhalation and burns.

The enormous, very public catastrophe set off a storm of rumours. Congress immediately began an investigation into the possibility of sabotage – America had been swept by a wave of Nazi spy paranoia, and the politicians took the opportunity to get tough.

Another rumour was that the Normandie had been a victim of the New York mafia. That story, encouraged by the mob, was that the fire was really a ruse to get Charles “Lucky” Luciano out of jail, so that the notorious crime boss could pressurise the New York City dockworkers union into beefing up security in the city’s ports. Lucky Luciano would make certain no further ships went up in flames – it was time for the mafia to take on all those Nazi secret agents.

It’s fitting that a vessel as flamboyant as the Normandie should attract outlandish theories about its demise. But, as the smoke cleared, a more prosaic story emerged – the fire was not down to secret agents or the mafia, but a welder, who accidentally set light to a pile of life jackets. They had been stored in the first-class area of the ship and were highly flammable.

Though the vessel itself suffered a terrible fate, the Normandie’s interior fittings are still around, many of them now considered art deco masterpieces, particularly the Lalique glasswork. Some of the murals from the ship’s first-class interiors are on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and fixtures from the Normandie’s colossal dining room doors now adorn the entrance to the Maronite Cathedral in Brooklyn.

As for the burned-out hulk of the once-glorious SS Normandie, it was towed out to Port Newark, New Jersey, and sold off for $161,000. By 1948, it had been entirely cut up for scrap.