Not that long ago, being a citizen of both the United States and the United Kingdom was an unalloyed privilege, a golden ticket. Before my burgundy passport arrived in 2004, I’d been a permanent UK resident since the late 1990s.

To be part of two flawed but fundamentally sound democracies, that looked outward to the world, was exhilarating. London and New York sometimes seemed a single city. And London was a gateway to Europe.

Then, along came Brexit and Trump. Both countries — fired by a fear of “the other,” of immigrants, of being left behind by the elites — turned in on themselves. National insecurity supplanted confidence. A growing coarseness poisoned politics.

As rifts and rancour spread, I could feel it coming. To paraphrase Theresa May’s noxious formulation, I, a citizen of the world, was becoming a citizen of nowhere.

I don’t mean to romanticise the US pre-Trump or the UK pre-Brexit. The US had been heading toward Donald Trump since the 1970s, when the Christian Right, spearhead of the culture war to come, began tightening its hold on presidential politics.

I remember being at George HW Bush’s house in Houston right after he abandoned his run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1980. During the campaign, Bush, an Episcopalian, had come under withering attack from extremist evangelical Christians who, among other cruelties, spread the falsehood that Bush’s wife, Barbara, had aborted a daughter. In fact, the Bushes had a child, Robin, who died of leukaemia at the age of three.

On that spring day in Houston, Bush stood tugging at his blue blazer, disgusted by the way religious conservatives had taken over his party. He said he could never wear his religion on his sleeve.

Eight years later, after he’d served as Ronald Reagan’s vice-president and was running for president once again, I watched him on television as an interviewer at a local station in Florida asked him if he was a born-again Christian. “Well,” he said, “if by that you mean…”. I didn’t need to hear any more.

In Britain, a number of roads led to Brexit. One of them began, not long after I arrived in the UK, amid Tony Blair’s efforts to cure what he called post-empire malaise. His idea was that Britain could secure its proper place in the world in two ways: by being an unwavering partner of the US — a misadventure that would crash in Iraq — and by being staunchly and unabashedly European. That would also end badly.

In 2004, eight central and eastern European countries, plus two Mediterranean ones, joined the European Union — the union’s largest single expansion in terms of the number of people and countries since its founding in 1993.

Because accession occurred not that long after the birth of the Euro, even some pro-Europeans worried the EU was doing too much too fast.

Among the older, richer EU members, there was nervousness about a westward tilt that would propel foreign workers into their labour markets, deepening resentment among economically insecure local populations.

Most pre-enlargement EU members imposed temporary restrictions on the employment rights of labourers from accession countries. Blair’s Britain did not. After all, the UK had experienced uninterrupted economic growth and a declining birth rate for a decade. It needed workers.

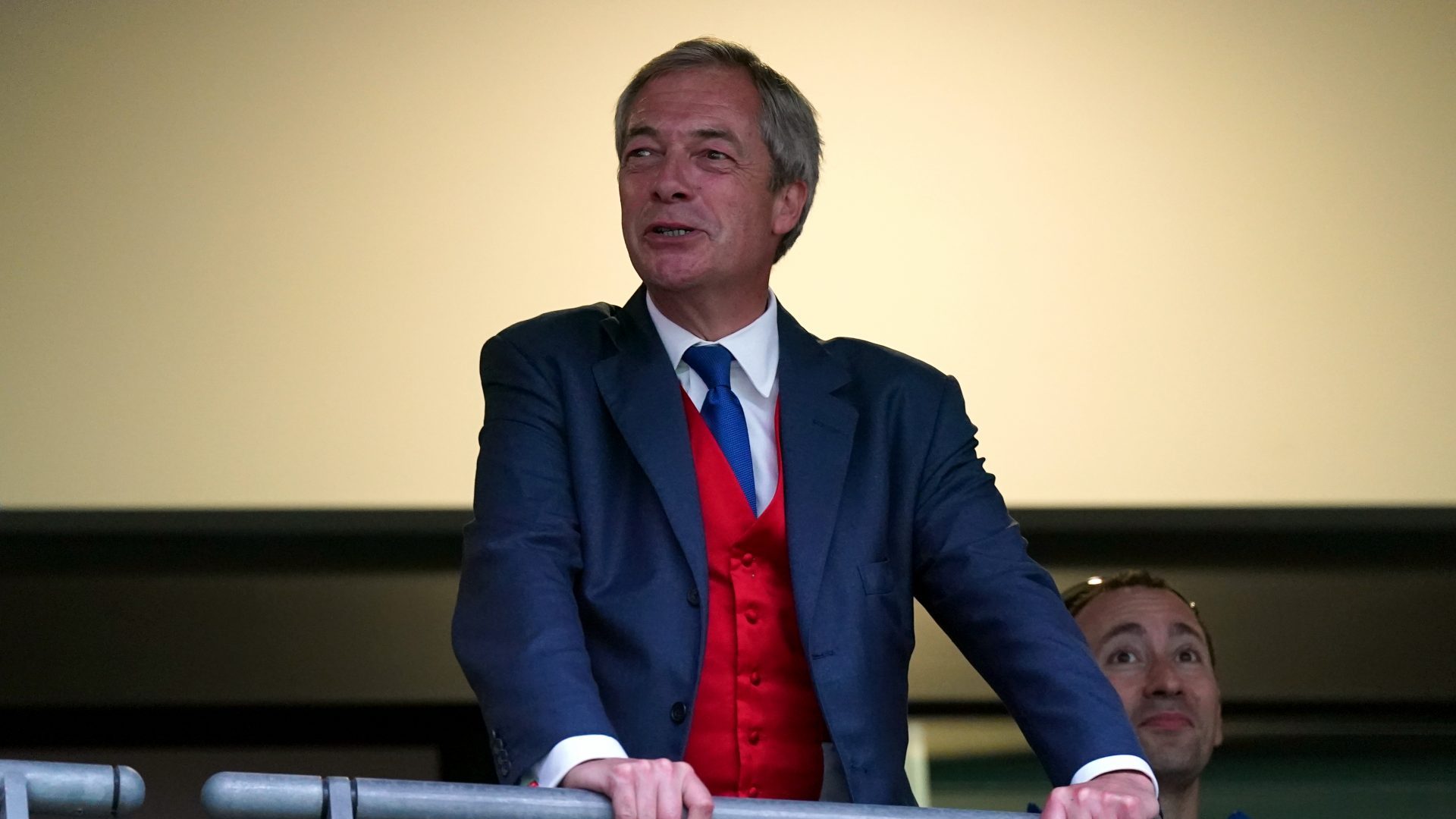

The doors flew open. Poles came in especially large numbers, making an increasing number of Britons uncomfortable. The economy’s absorptive power was impressive. Even after the 2008-2009 financial crisis slammed economic growth into reverse, the UK’s Polish population would more than double, reaching a peak of more than one million in 2017. It hardly mattered that economic arguments supported immigration. New Labour was history. The electorally weak Conservatives were running scared of Nigel Farage and his anti-European, anti-immigrant nativism. Politics got uglier and uglier.

A relatively small thing, but a sign of the times: after the 2016 referendum, I walked from home over the Thames to the Polish Social and Cultural Association (POSK) in the borough Hammersmith and Fulham, which had voted almost 70% in favour of Remain. Vandals had attacked the building and scrawled “Fuck You” on the windows.

Two countries, the US and the UK, whose differences complemented each other, now feel too alike in their venality.

My next UK passport is even going to match the colour of my American one. The stains of Brexit and Trump are not going away soon. Never before have I known so many people, here and there, who are seeking alternative citizenships. I’m not one of them. I don’t really have a choice, and even if I did, London is home.

I’m stuck between a rock and a hard place — or as the classics buff temporarily residing at 10 Downing Street might put it, between Scylla and Charybdis.

There are many worse monsters out there.

Award-winning journalist Stryker McGuire, a New Yorker, was Newsweek’s London bureau chief from 1996-2008. Most recently, he was a senior editor at Bloomberg Markets.