As 77-year-old Ron Mael rose from his piano and danced triumphantly across the most famous stage in Britain, it was the culmination of a lifetime’s dreaming of “becoming an English band”. With his flamboyant, falsetto-voiced younger brother, Russell, out front, Ron is the usually quietly steely creative centre of Sparks, the world’s foremost purveyors of witty, idiosyncratic pop, and the greatest cult band ever to come out of America.

Last week, Sparks’ two consecutive sold-out nights at the Royal Albert Hall – “the pinnacle of British music venues for us,” they said – was the crowning of a career-long Anglophilia and constant cross-pollination with British and European artists. And with their new album, The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte, littered with continental references, from Monoprix to Monet and the Mona Lisa, Sparks’ love affair with Europe doesn’t look as if it is likely to cool anytime soon.

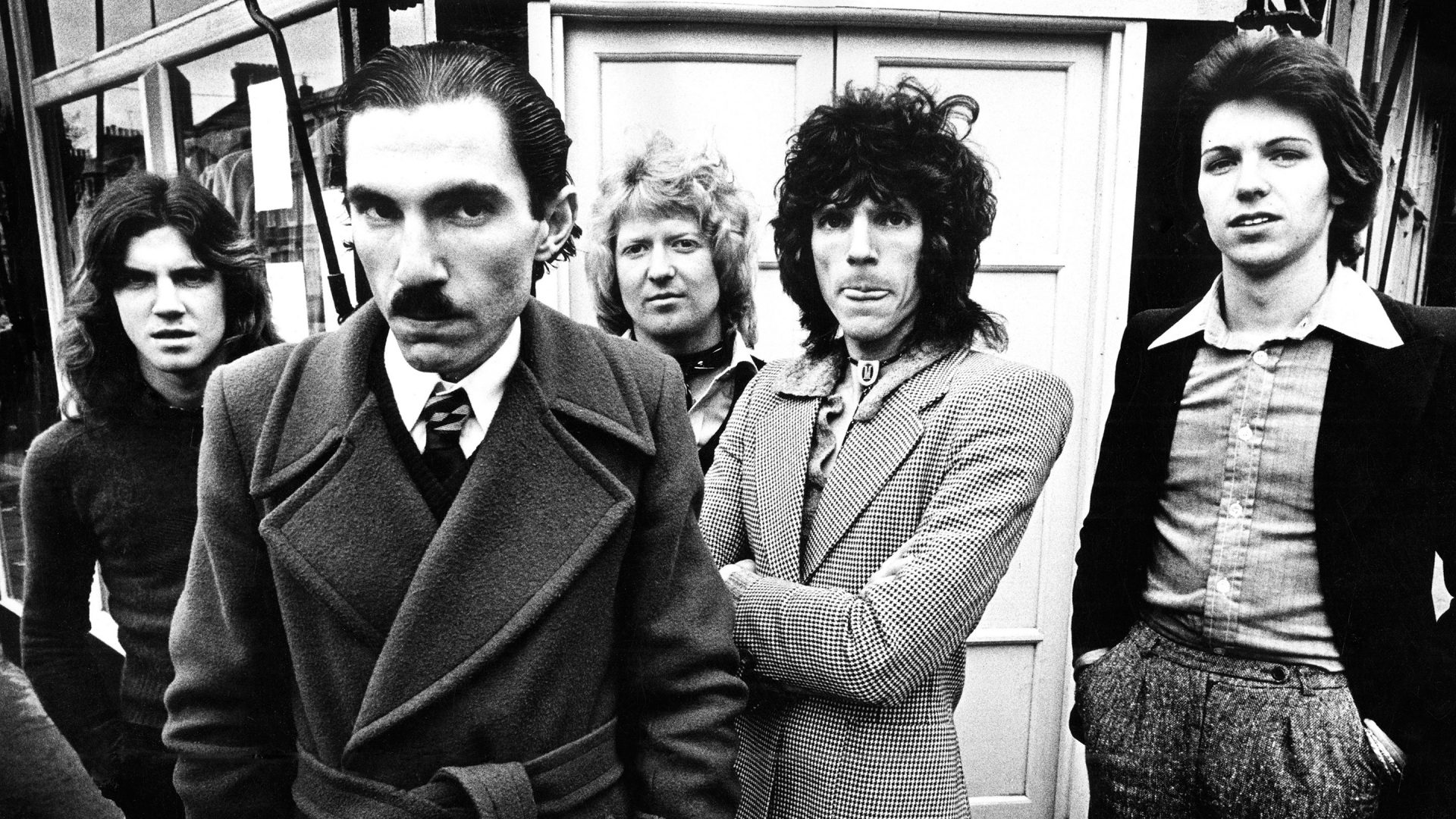

Sparks’ first two albums had clear echoes of the storytelling songwriting of Pete Townshend, the lyrical wit of Ray Davies, the pop genius of Roy Wood and the mad creativity of Syd Barrett, and when their breakthrough came, it was on the home soil of these idols. This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both of Us (1974) was the most eccentric record in the history of pop, and they bucked all expectations of American bands when they performed it on Top of the Pops that summer, from Ron’s Charlie Chaplin moustache and Marcel Marceau-esque expressions, to Russell channelling the louche androgyny of Marc Bolan and strutting stage presence of Mick Jagger.

The single rocketed to No 2 in the UK and was also a hit in mainland Europe, but the Maels then followed it up with a deeply unconventional choice, Girl From Germany, the story of American Jewish parents meeting their son’s German girlfriend (“They can hear the storm troops on our lawn when I show her in/ And the Führer is alive and well in our panelled den”). Never driven by commercial concerns, by the late 1970s Sparks were fading from view.

Salvation came from Europe. They made No. 1 in Heaven (1979) in Munich with the Italian electronic pioneer Giorgio Moroder, and the LP’s cutting-edge sounds became a touchstone for a whole generation of 1980s British pop music. The first single Vince Clarke ever bought was This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us, and both his early sound in Depeche Mode and his Ron-like deadpan presence behind a keyboard in Erasure clearly showed Sparks’ influence. Later, his remix of comeback single When Do I Get to Sing ‘My Way’ (1994) was final confirmation of their symbiosis.

While LP Terminal Jive (1980) had been big in France, and there were collaborations with Belgian originals Telex and the outrageous French couple Les Rita Mitsouko, British musicians held an enduring fascination for the Maels. Their single Lighten Up, Morrissey (2008) was a typically twisted tribute to the mercurial Smiths frontman and lifelong Sparks fan. Then came FFS (2015) with Franz Ferdinand, whose archness was always very Sparkean. From the sprawling suite Collaborations Don’t Work to the laugh-out-loud-funny Piss Off, the album was proof of the essential synergy between the Maels and the British.

But it would be on the Continent that the brothers – former UCLA film students and committed Franco-cinephiles – would realise their ambitions in that other medium. While a project with Jacques Tati had fallen through decades before – a matter of career-long regret – 2021’s rock opera Annette, made with the French director Leos Carax, was a kind of redemption, winning three Lumières and five Césars.

With The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte, Sparks are still doing what they have always done best, from their unrivalled ability to paint tragic little pop vignettes on the sparse Escalator (“I’m going up/ As she’s going down/ One fleeting glance/ There ain’t no chance”), to their baroque drama and savage wit on Not That Well-Defined (“I can picture actors I don’t know/ But I can’t imagine you at all”).

Sparks still don’t sound quite like anyone else, and it is yet to be seen how this latest masterpiece will influence musicians on this side of the Atlantic. Their journey as a musical invasive species goes on.