“Dreadful with grinding of ice”. This was how William Morris described Iceland when he first laid eyes on its landscape in the summer of 1871. In the midst of marital strife, his wife having gone off with his close friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and keen to visit the settings of the Icelandic sagas, which he was then translating, Morris found the country to be hostile, rocky, and the antithesis of the bucolic Englishness that typified his designs.

But the shock of Iceland would turn out to be galvanising for Morris. Those barren landscapes would show up in the otherworldly settings of his fantasy novels of the 1870s. The harsh simplicity of Icelanders’ lives highlighted the frivolity of the Victorian bourgeoisie and hastened his turn to revolutionary socialism. And Iceland’s unspoilt nature threw the dirty air of a rapidly industrialising Britain into horrifying relief. “Iceland, by contrast,” wrote the late Morris biographer Fiona MacCarthy, “was purity itself”.

That purity is now under threat. And as the world casts its eyes on the Fagradalsfjall volcano a century and a half on from Morris’s life-changing visit, another type of artist – musicians – are still finding unique inspiration in Iceland’s landscape.

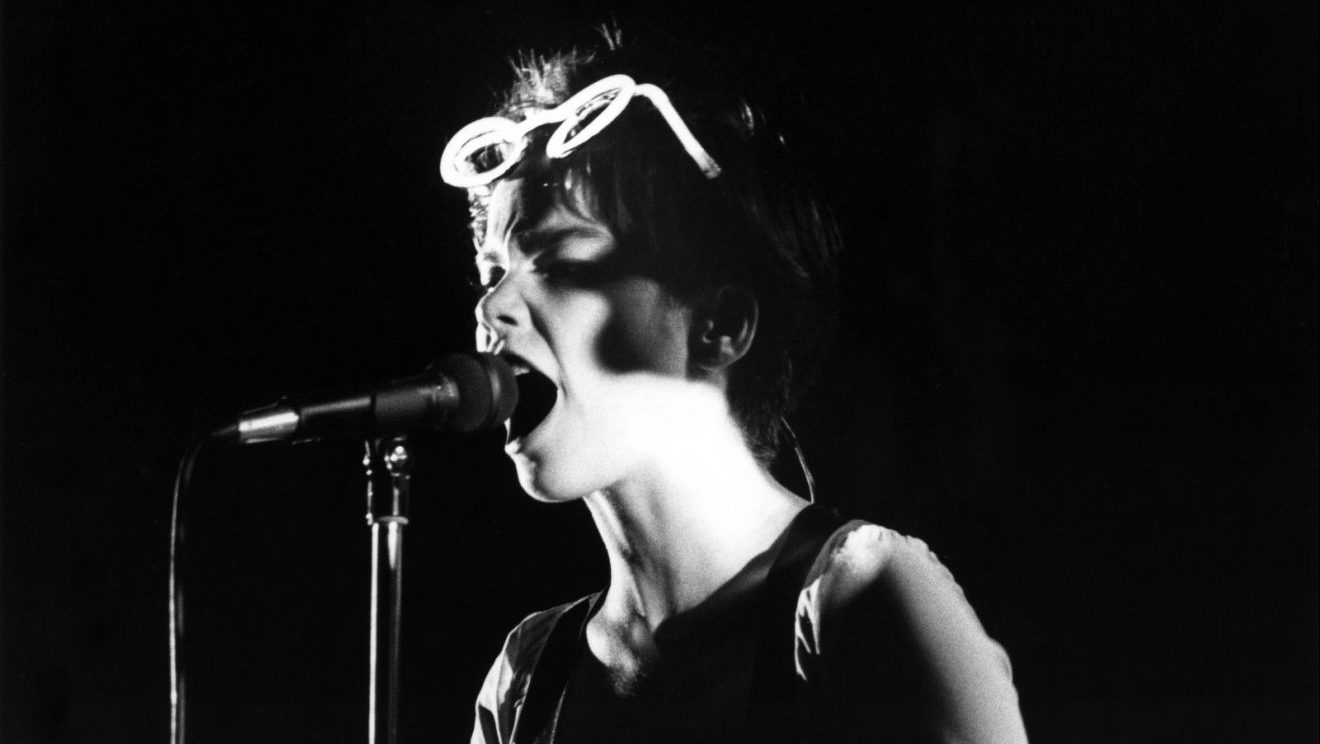

In early October, Björk – by far the country’s most famous artist, three decades on from the release of her debut LP – unveiled a surprise song with Spanish popstar Rosalía in support of the fight against an industrial fish farm being established in the Seyðisfjörður fjord. The hypnotic acapella track was accompanied by a statement where she pointed out that “Iceland has the largest untouched area in Europe. Here in summer sheep have been free in the mountains, birds have flown over them and fish have been swimming unchecked in rivers, lakes and fjords.”

Björk has been campaigning against the destruction of this raw vision of Iceland for years, just as she has repeatedly evoked those treasures sonically. She described last year’s Fossora – recorded in her homeland during lockdown and taking the theme of mushrooms as a symbol of ecological survival – as an “Iceland album”. She founded the Náttúra Foundation in 2008 to work against the expansion of the aluminium industry in Iceland, also releasing a rare Icelandic-language fundraising single with the feel of a battle cry, and she later campaigned against the laying of a powerline through the country’s highlands.

But it was 1997’s Homogenic that was Björk’s biggest tribute to Iceland. Through broken beats, epic strings and a constant sense of unease, it was intended to sound like the country’s “rough volcanoes with soft moss growing over it”, as she instructed one of its producers. Homogenic reflected the alpha and omega of Iceland, rather as Morris experienced it, as a paradox of beauty and terror, the inspiring and the stultifying, from the opener Hunter, whose magisterial ominousness is fitting of the awe-inspiring landscape, to the truly ethereal closing track All Is Full of Love, based on the Ragnarök of Norse mythology.

Louise McCraw knows first-hand the qualities of Iceland that are reflected in Homogenic. “I think Iceland calls for sparse,” she says, “because there’s not a lot to look at, it really makes you think about what you’re putting in a song – the elements really matter. You don’t want to overcrowd it because Iceland itself isn’t overcrowded and adding too much to the landscape would ruin it.”

The former member of Glaswegian dream pop band Skjør took up an artist’s residency in the country in late 2019, staying in the far-flung town of Þingeyri in the Westfjords (keep going west over the Dýrafjörður fjord and you will end up on the east coast of Greenland).

McCraw’s album Human Danger, released under the moniker Goodnight Louisa and reviewed here in TNE last year, was the result of that stripped-down approach demanded of the Icelandic landscape, which nonetheless, McCraw says, calls for a “vastness” of sound.

McCraw points to the thunderous, shimmering track Judith as one “fully written there from scratch” that has just that quality. “Every time I listen to it, it’s just very vast. I think that’s the thing about Iceland – it’s not the biggest country in the world, but it’s so vast, it feels like you could walk off the end and come back on the other side.”

Indeed, McCraw’s description of the “miles and miles and miles of snow deserts” on the long drive north from Reykjavík recalls Morris’s observation that “it is an awful place… emptiness and nothing else”. McCraw also makes no bones about the “weird” people she encountered there – reiki fanatics, work-hardened fishermen, an old woman who played the organ in her living room while the radio blared in the background.

Morris, meanwhile, encountered Icelanders as “lazy, dreamy, without enterprise or hope: awfully poor, and used to all kinds of privations – and with all that gentle, kind, intensely curious.”

And it is indeed in terms of paradox that McCraw too describes the country. McCraw calls the experience “isolating”, yet says “you didn’t ever really feel alone” there, citing the “underlying presence of an energy, almost like a low hum – you could feel the history of the place”.

It’s a place where, she says, you experience the jagged “spines” of the fjord peaks menacingly “looming over you”, but “it’s almost weird to say, but it’s also almost quite motherly”.

Fossora ruminated on the maternal nature of the Icelandic landscape via the recent death of Björk’s own mother, and now another artist has also found Iceland fertile ground for a meditation on motherhood in a world under threat.

“It kind of became like a band member,” says genre-defying Danish artist Myrkur (Amalie Bruun) of recording her new album, Spine, in Iceland, “the landscape started to have an influence on the sound”.

Working at Sundlaugin, the studio just outside Reykjavík belonging to Icelandic musical giants Sigur Rós, the artist whose back catalogue ranges from pure folk to screaming black metal made a turn to a more electronic sound for this new LP, using analogue synths to add “little sprinkles of chromatic colour”. She characterises the resulting sound as “open, vast, shimmery, starry”, with the track Mothlike – a full-blown synth-led track that seems to have escaped from the 1980s – marking a clear departure.

“I recorded in Los Angeles, and it’s too normal,” Bruun says. “And then you’re here, and there’s a waterfall and there’s a mountain and you can just completely sink yourself into the process of recording music”. The LP’s opening track Balfaerd (Viking Funeral) with its mournful folk fiddle, insistent drone and wordless choral voice, conjures up mental images of that barren yet beautiful landscape, but also culminates in a sense of taking off into the stratosphere. It feels as if we are going to another planet, and Bruun confirms she arrived in the country and “it was like, OK, unplug, we are landed on the moon”.

But the underlying driving force of Spine was the experience of another kind of alienation that leads to a new world – becoming a mother. The isolation of early motherhood is reflected in the album’s lead single Like Humans (“Talk to me like humans do/ Everyone stays away”), but the shimmeringly monolithic title track, with its by turns delicate and anthemic vocal, ominously building black metal guitars and thunderous percussion, is both a clear match for the Icelandic landscape and that rare thing – a song about the bond between mother and child:

“My body made your spine / You and I intertwine / You made me human / Stay with me / You will be / The one I love the most”.

“We’ve never been further from the human experience than we are now,” Bruun says, citing the disconnecting effects of “AI, screens and the metaverse. And then when you become a mother and you create a human it changes everything.”

The closing track of Spine, the beautiful lullaby Menneskebarn (Child of Man), stands as a kind of prayer for a better world for our children. “I want my son to live with nature and human relationships,” she says, “so at the end of the album, I wanted to just put a happier ending, just an ode to that and to childhood.”

It seems that for some artists Iceland’s untamed nature speaks to the very fundamentals of humanity – birth, life and human connection. And while Morris’s “dreadful” Iceland is certainly reflected in the atmospheres of Spine, so is the way the country sparked concerned reflection on a current dystopia, but also nourished utopian dreams.

Myrkur’s Spine is out now on Relapse Records. Goodnight Louisa will be releasing new music next year