As Camilo Sesto prepared to take the stage in the role of his life, his life was also quite possibly in danger. Sesto – a smooth-as-silk balladeer who had enjoyed an almost unbroken string of No 1 singles in Spain since his breakthrough three years before – had defied the conservative Catholic values of the Franco regime to stage Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s Jesus Christ Superstar in Madrid.

The street outside the theatre on that opening night in November 1975 was a circus. Fired up by the opprobrium of the regime-controlled press, protesters picketed the entrance – a priest threw himself to his knees and fervently prayed in expiation for the blasphemy to come.

But more concerning was the interest taken in the production by the Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey, a far right paramilitary group. They had intimidated ticket-buyers and had also issued a bomb threat against the theatre.

The group had form when it came to targeting cultural works that they found ideologically offensive – in 1971, it had staged an acid attack on a Madrid exhibition honouring Picasso’s 90th birthday. By late 1975, tensions were at an all-time high – Franco lay dying at El Pardo Palace, less than 10 miles north of the capital, and fascists were fighting for the survival of Francoism beyond his lifetime. Tensions were so high that, for Sesto, there was a real risk that his portrayal on stage of Christ’s bloody death could be followed by his own.

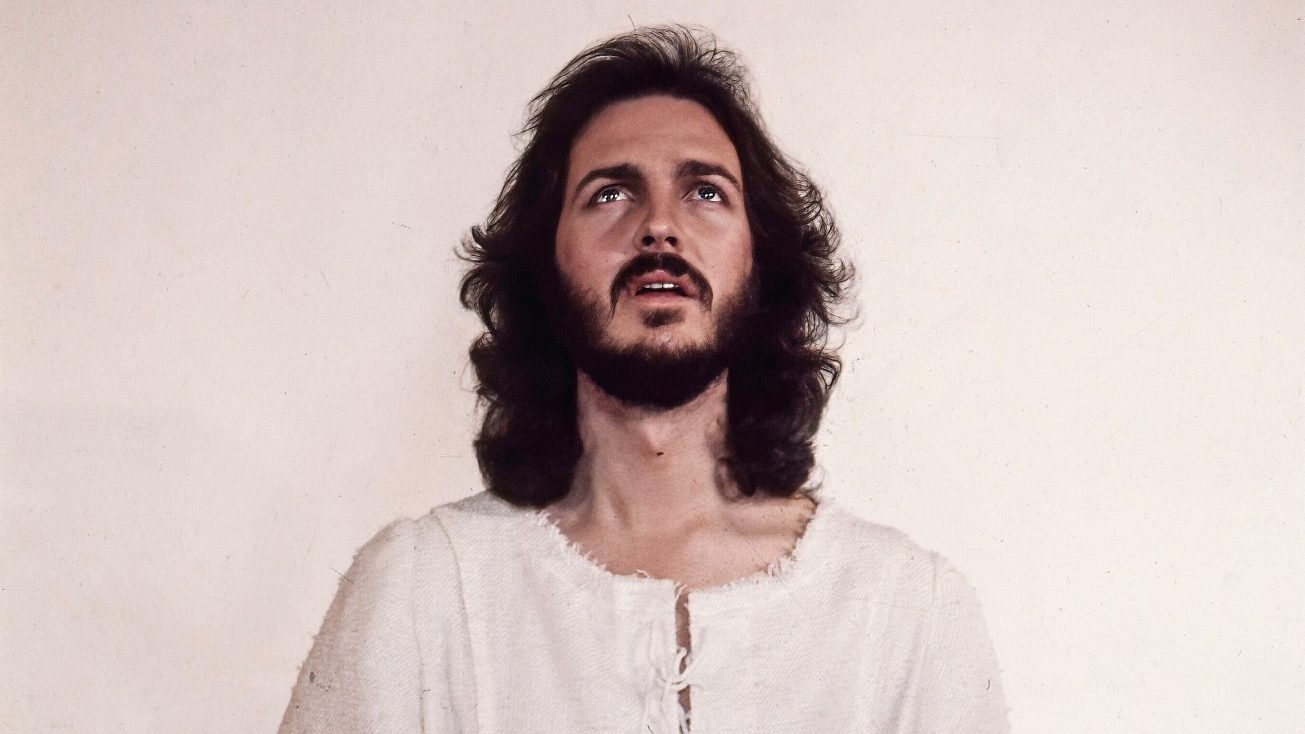

Sesto was an unusual figure to be at the centre of such a politically charged situation. With beautiful, sparkling blue eyes and a dynamic stage presence, he had a flamboyant star quality. Beyond this surface appeal, his expertly crafted, self-written and self-produced songs and the emotional dexterity of his vocals made him a formidable musical force.

Sesto often claimed to have sold 200m records. This was probably a not-uncharacteristic exaggeration – but there is no doubt that his songs became part of Spanish life. And yet, despite this mainstream reputation, for one key moment in the nation’s history, he became the central figure in an act of profound cultural subversion.

The story of Sesto’s era-defining show began three years before, in the summer of 1972. His breakthrough single Algo de Mí – an agonised break-up ballad that set the tone for the rest of his career – was halfway through its 11-week run at No 1. At the same time, Jesus Christ Superstar was making its West End debut in London.

Sesto was an established star as he sat in a state of rapt attention amid the Victorian grandeur of London’s Palace Theatre watching the show. He knew instantly he had to bring Jesus Christ Superstar to Spain – naturally, he would take the role of the Messiah. “I returned to Spain completely insane and willing to do everything in my power to make the project a reality,” he later said. “It just seemed like a perfect play for the time we were living.”

There were some slight impediments to this ambition. First, while Broadway musicals were not alien to Spain, rock opera was a novel concept and therefore a commercial risk. Second, Sesto’s image could not have been further from the show’s depiction of Jesus as scruffy, angry and arrogant – it seemed like career suicide.

Finally, and most crucially, in Franco’s Spain the arts were heavily censored, with religion the most sensitive of subjects, and some musicals had been banned in the recent past. While Hair!, for example, popularised the counterculture on stages across Europe, Spain had to make do with strange ersatz versions that exploited the notoriety of the original but omitted its swearing, sex references and nudity.

Yet, by the mid-1970s the country was experiencing the liberalising effects of mass tourism, and even some conservatives were calling for a loosening of censorship, believing that concessions would have to be made if Francoism was to survive in changing times.

In 1974, Godspell was staged in Madrid, albeit with Franco-supporting writer José María Pemán brought in to translate the text. That same year the film version of Jesus Christ Superstar, which had initially been banned, was permitted a release, but with key lines adapted.

In late 1975 Hair! finally appeared on the Madrid stage, performed in modified form by a touring American production. But there were no guarantees that Sesto’s project would happen – until the overture struck up on opening night, it was not certain whether the Spanish performance of Jesus Christ Superstar would make it on to the stage.

For six months, Sesto worked on getting the production up and running. In that time, the Greek-flavoured Melina became his sixth No 1 and the hit of summer 1975. That was quickly followed by his lushly romantic and much-loved Jamás, which would just miss out on the top spot. Both songs appeared on Amor Libre that autumn, widely considered his greatest album, and Sesto’s commercial success was hardly in doubt as he made preparations for a huge career gamble. It was a financial gamble, too – with no one apparently interested in investing in such a risky enterprise, he funded the show entirely himself, to the tune of millions of pesetas.

But Sesto’s recruitment of some remarkable personnel meant that the project was not merely a shot in the dark. Romanian-born Gelu Barbu, once the principal dancer with the Kirov Ballet, was the choreographer. Dick Zappala, singer with the Spanish prog band Araxes, made a suitably barmy King Herod. Beautiful Dominican rising star Ángela Carrasco was born for the Mary Magdalene part.

Rocker Teddy Bautista not only appeared as Judas but was also musical director, bringing an experimental flavour to the score that drew on his mind-bending LP Ciclos (1974), an electronic take on Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. His group Los Canarios, which had had a hit with the soul stomper Get On Your Knees in 1968, were the house band, lending the show the necessary rock heft.

Perhaps most credibly, Jaime Azpilicueta, whose work in legitimate theatre included everything from Sophocles to Camus, was brought in to translate the show into Spanish and to direct.

In the end, Azpilicueta’s text did not pass the censors. Lyrics had to be changed. The plan to have Herod appear in drag was hastily abandoned. But the ideas that had caused controversy even in the US and UK – of Christ having doubts about his mission and the implied romantic relationship with Mary Magdalene – did survive, and were finally seen on opening night. There were no bombs, as it turned out, but the shockwaves that the debut of Jesucristo Superstar sent out meant there might as well have been.

The critics were primed and ready. In the conservative paper ABC, veteran theatre critic Adolfo Prego condemned the show as trivial and irreligious, and explained away the six-minute standing ovation as purely down to the undeniable impressiveness of the “spectacle”.

In the church-controlled arts magazine Blanco y Negro, Falangist playwright Pablo Villamar, whose politically orthodox rip-off Jesucristo Libertador had preceded Sesto’s production by weeks, emphasised that the show was not for those who “are against abortion, homosexuality, and other scourges that the western world has been bringing us”.

Some on the left were also unimpressed, with the journalist and musician Moncho Alpuente, later a key figure in the Movida Madrileña post-Franco counterculture, condemning it as the commercialisation of alternative values. But many others saw the show as a cultural milestone. The music critic Luis Carlos Buraya at reform-leaning paper Ya declared it better than the London production.

Joaquín Luqui of the music paper El Gran Musical wrote: “The opening night of Jesucristo Superstar now goes down in the history of the great personal and theatrical events of all of us who were there.”

Even Arriba, the official organ of the Falangists, found positive words, albeit in their own vernacular, saying that Sesto “brought a religious emotion to his performance that distanced him from any stardom”. With the cast album hitting No 2 and spawning the show-stopping Gethsemane as a Top 20 single, Jesucristo Superstar was, without any doubt – and completely against the odds – a hit.

Fifteen days after it opened, Franco died. As a sense of release swept the streets of Madrid, the public embraced the show and it ran for nearly five months, only curtailed by Sesto having to go on tour.

A new Spain was not immediately born with the death of Franco; the pangs of the transition to democracy continued into the early 1980s, and Sesto’s image, like so many things in those years, developed conflicting meanings. While Jesucristo Superstar had been a watershed, balladeers like him were always identified with the anodyne popular culture of Francoism. His peers Julio Iglesias and Raphael had represented Spain at Eurovision at a time when it was exploited by the regime for its soft power (Iglesias was associated with the right via his father, a Nationalist fighter and famous gynaecologist well connected in the regime). Sesto’s reputation suffered for being categorised alongside them.

Even if many viewed him as a relic, Sesto never went away. Immediately after Jesucristo Superstar finished its run, Gillette offered him $50,000 to shave off his beard. A philanthropist throughout his career, he donated the fee to a children’s charity.

He became ever more glamorous – performing signature song Vivir Así Es Morir de Amor (To Live Like This Is to Die of Love) on variety show 300 millones in 1979, he was pure showbiz glitz with his white suit, medallioned chest and bouffant hair.

Another No 1, Perdóname, came in early 1981 and was one of his most beautiful songs. He continued to shift albums by the million, and wrote and produced extensively for other artists. On the vast Latin American market he was huge, touring there frequently.

Inherently camp, Sesto became a gay icon, just as his good looks had made him a “housewives’ favourite” from the start.

In later decades he became something of a tragic figure, struggling with alcohol and seemingly equally addicted to cosmetic surgery. He died in 2019 at the age of 72, leaving his entire fortune to his son, also called Camilo, whose own struggles with addiction continue to be mercilessly exploited by the Spanish gossip magazines.

But Sesto’s legacy lives on. Huge Latin pop star Nathy Peluso released an R&B-inflected cover of Vivir Así Es Morir de Amor in 2021, and the saga of Jesucristo Superstar was dramatised in the TV miniseries Camilo Superstar in 2023. A museum dedicated to Sesto is due to open in his hometown of Alcoy, Alicante, this year. Sesto is a feature in the landscape of Spanish cultural memory that will never go away. His remarkable role in the moment when Spain entered a new era should not be forgotten.