When singer-songwriter and embodiment of 1960s French cool Françoise Hardy died last week at the age of 80, the British media defined her in terms of her spellbinding effect on major rock stars.

Mick Jagger, we were told, said she was his “ideal woman”. Bob Dylan had dedicated a poem full of Parisian imagery to her and put it on the back cover of Another Side of Bob Dylan. David Bowie had said simply, “I was passionately in love with her.”

This was superficial since her connection to each was fleeting: a dinner and a photoshoot with her male doppelganger Jagger; an awkward backstage meeting with Dylan at the Paris Olympia in 1966; appearing on a French TV show in 2003 with a clearly starstruck Bowie. But Hardy’s importance as an artist always needed “translating” in such a way for an English-speaking audience, her intense lyrical poetry and songs of suffering and doubt leaving her as a cult figure.

Even so, at a specific moment in history, Hardy achieved fleeting mainstream success in Britain when her broken-hearted rock’n’roll ballad Tous les garçons et les filles cracked the UK Top 40 in the summer of 1964. The following year the similarly wistful Et même almost reached the Top 30, but it took a switch to English on All Over the World – an English-language version of Tous les garçons with execrably clunky lyrics – to hit No 16. She never troubled the UK charts again.

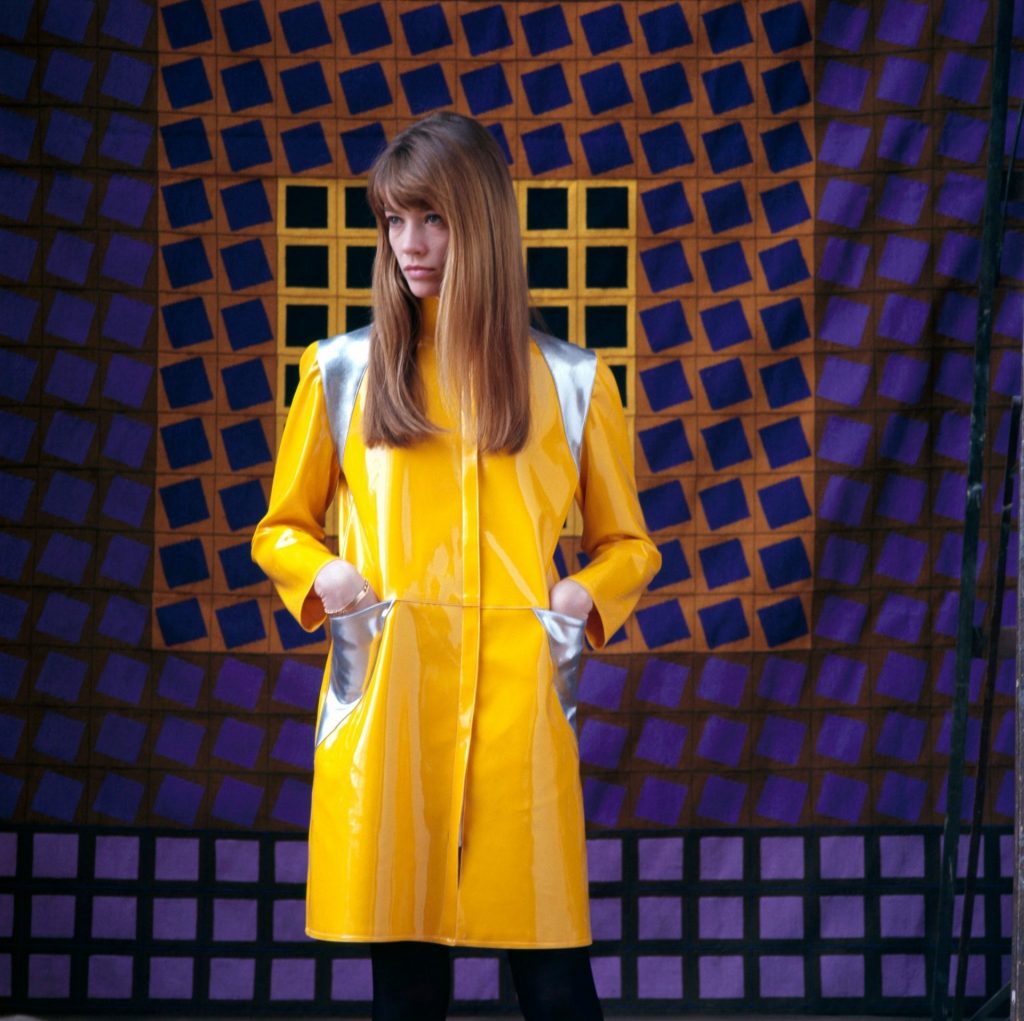

Hardy’s appeal was clear. With model looks and a perpetual wistfulness about her, she was one of the clique of war baby Parisiennes who represented yé-yé – the French take on American rock’n’roll with a large handful of chanson thrown in. Yé-yé was just one European export – like Italian tailoring and Nouvelle Vague cinema – by which fashionable British teenagers signalled their street cred in that era, and Hardy was a figure who instantly stood for the effortless sophistication of French culture.

Tous les garçons et les filles had in fact been a major hit in France almost two years before, captivating the nation at a politically heated time for both the country and the world.

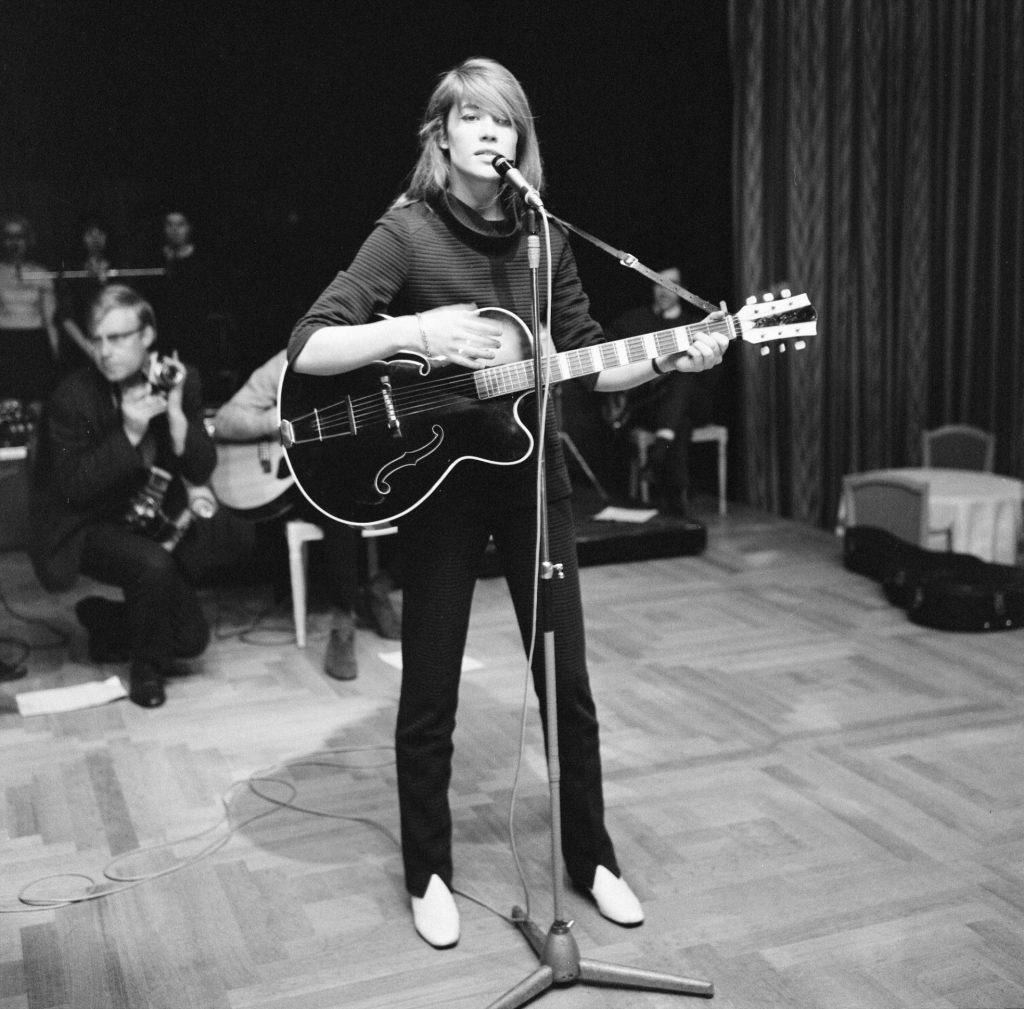

The aftershocks of the Cuban missile crisis were still rumbling in late October 1962 as France awaited the results of Charles de Gaulle’s referendum on the direct election of future presidents of the republic. During an interlude in the TV coverage of the referendum, Hardy performed the breakthrough song and it was the moment her career truly started.

As the 18-year-old sang dolefully “Tous les garçons et les filles de mon âge/ Se promènent dans la rue deux par deux” (“All the boys and girls my age/ Walk down the street two by two”), concluding “Mais moi, je vais seule par les rues, l’âme en peine” (“But I go alone through the streets, my soul in pain”), the French were charmed and Hardy became an instant star. The song spent 15 weeks at No 1 between October 1962 and April the following year.

Hardy later acknowledged “it was my first and most important hit” but added “unfortunately, as it’s not my best song!” It was certainly better than the A-side from the same EP, the comparatively inane Oh Oh Chérie, a cover of Bobby Lee Trammell’s novelty, hiccupping 1958 song Uh Oh. That song had not been her choice, and it was highly unusual in the manufactured world of yé-yé that Hardy had written Tous les garçons herself.

By the time her success in Britain came, Hardy had already made moves to take control of her career. She came to London, where the best session musicians were to be found (Jimmy Page was among them and recorded with her), and found a freedom that was absent in Paris’s pop hothouse.

While Hardy the icon became a face of the decade, working with legendary names across film and fashion – Vadim and Godard, Saint Laurent and Rabanne – Hardy the musician was disillusioned with all the glitz, gave up live performance, and moved in an ever more serious direction.

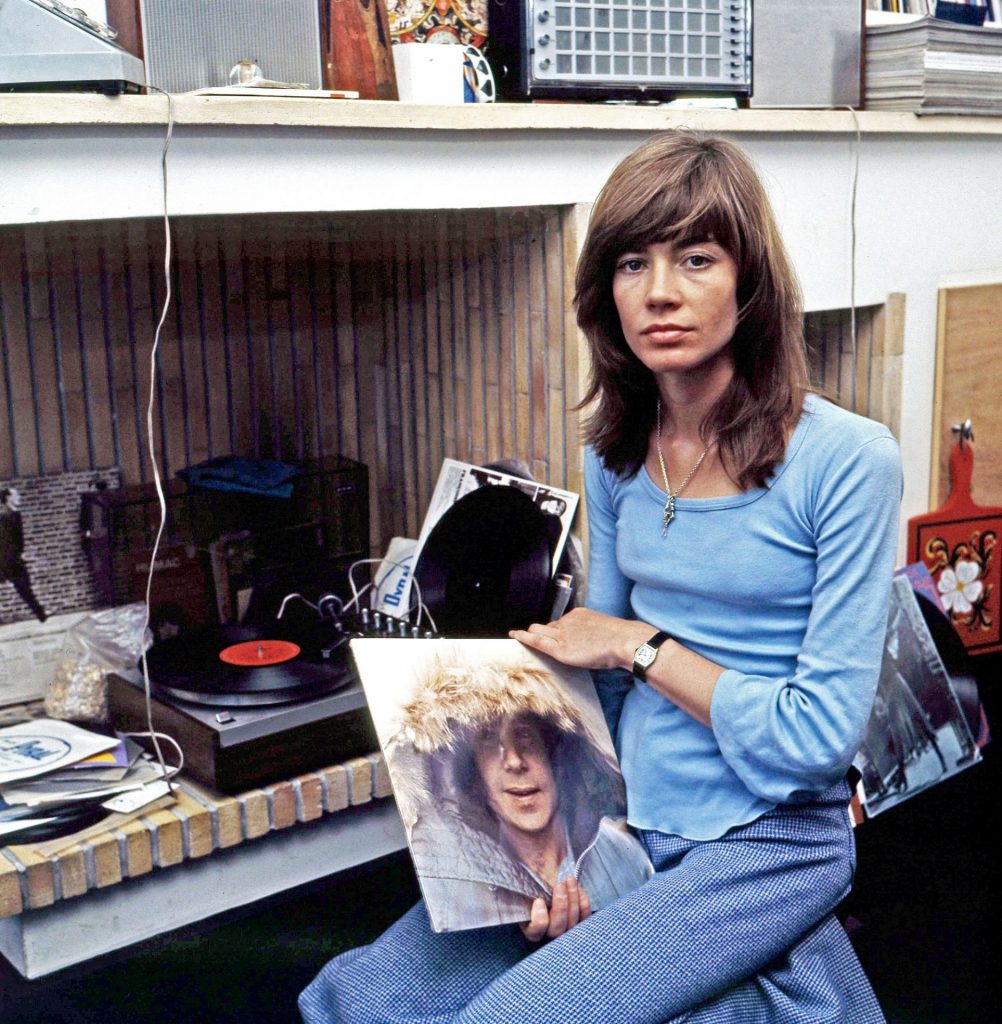

Hardy covered Leonard Cohen’s brooding Suzanne to magical effect in 1968, but it was not until her eponymous 1971 album, known as La question after its delicate stand-out track, that Hardy decisively left her yé-yé reputation behind. Even the cover, showing her in stark black and white, head tilted back and chin defiantly thrust forward, suggested steely maturity in place of girlish coquettishness.

An intensely personal album, La question dealt with the existential and the erotic, and it remained her own career-long favourite. She next worked with celebrated songwriter Michel Berger on 1973 LP Message personnel – where La question had been sparse, this was an album on a grander scale of lush strings and emotional drama.

While the 1980s were rather fallow, Hardy consistently showed an ability to take surprising directions in the following decades. She worked with younger artists, appearing on a reworked version of Blur’s To the End in 1995, and putting her vocals to the B-side Jeanne on French electronic duo Air’s breakthrough single Sexy Boy (1997). In between she released an album of convincingly moody alt-rock, Le Danger.

Hardy’s final album, Personne d’autre (2018), was released when she was 74, after years of cancer treatment and a near-death experience. Consequently, it was an album which contemplated mortality and it contained not a single banal platitude to sugar the pill. See, for example, the lyrics to Un seul geste – “Ni direction, ni boussole, ni signal, ni repère… Nul part les mots qui consolent qui rassurent ou éclairent” (“No direction, no compass, no signal, no landmarks… nowhere are the words that console, that reassure or enlighten”).

Yet, speaking about the album at the time, she emphasised her “acceptance” of death. Inherently a spiritual seeker, Hardy had studied astrology, even writing two books on the subject, and she hoped death would mean she would finally “discover the mystery of the cosmos”.

She had also long contemplated the subject as a vocal supporter of assisted dying. Her mother, suffering from a debilitating nerve disease, had chosen euthanasia, and as cancer left Hardy with an ever-reduced quality of life, last year she called directly on Emmanuel Macron to legalise assisted dying in France.

In her personal life, Hardy had nothing in common with the rock stars who lusted after her. She was a shy ex-Catholic schoolgirl who was utterly unstarry, modest about her “limited voice”, and who had a devoted lifelong relationship with fellow musician Jacques Dutronc.

Their relationship was unconventional, however – their son Thomas was born out of wedlock, they later married only for “financial reasons”, and they remained close even after they separated – and its complications were the inspiration behind some of Hardy’s greatest songs.

Ultimately Hardy was a romantic, but one under no illusions about the harsh realities of love. “Love is a remarkable force, even if its price is perpetual torment,” she said. “But without that torment, I would not have written a single lyric.”