In Extremadura, trees are a way of life. The evergreen holm oak, encina in Spanish, is the emblem of the region and the dehesa is all around – about a million hectares of it.

Dehesa is the name for the type of countryside that predominates in Extremadura (and in southern Portugal, where it’s called the montado). From the Latin defensa, meaning fenced off, it is the rolling pasture land dotted with holm and cork oaks (alcornoque), where freerange pigs rummage for the acorns that make jamón ibérico the world’s finest ham. Blue skies and cotton ball clouds complete the picture.

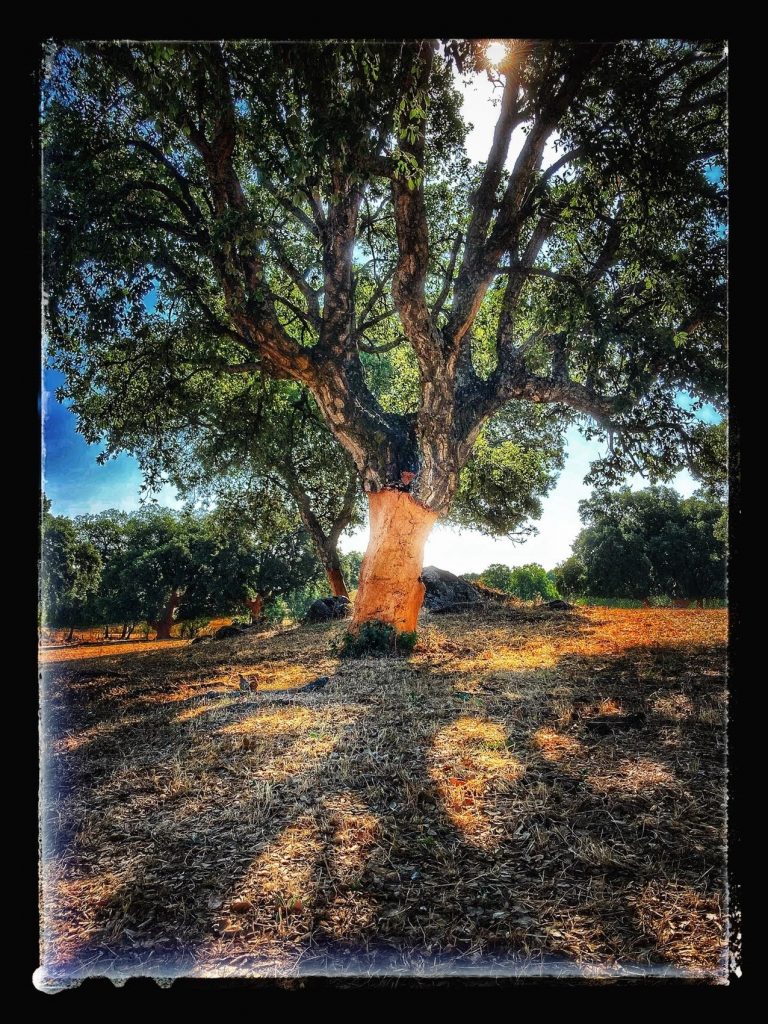

For centuries, the agricultural system of the dehesa has been the backbone of the local economy. Pigs, cows and sheep graze under the shade of the trees, providing food and wool. Pollarded branches provide firewood for heating and charcoal for cooking, mushrooms and honey are abundant, and every nine years or so, farmers can strip and sell the bark from their cork oaks, leaving the trunks red and naked. You don’t get plastic corks around here.

The dehesa is also a habitat for some of the most diverse and spectacular wildlife in Europe, including the Spanish Imperial Eagle, hordes of black vultures, and the rare Iberian lynx. This is the only place I’ve seen a road sign declaring “Caution: lynx crossing”, although I have yet to encounter one. Once, as we drove along a mountain ridge, an eagle with a vast wingspan kept us company, gliding alongside the car at wing-mirror level.

At first sight, the gnarled, low-spreading oak forests appear entirely natural, but if you look carefully at a section of dehesa from across a valley, you can make out the once orderly rows of trees planted hundreds of years ago.

At our finca (farm) near the border with Andalucía, we’re surrounded by oak trees, but there are gaps too. It is against the law to cut down healthy oaks, but the natural lifespan of a tree is around 250 years and every winter old age, disease and storms will claim a few more.

Desertification is a huge and growing problem across Spain as unsustainable farming dries up the aquifers and climate change batters the land. And as younger generations leave the countryside in search of easier ways to make a living, the upkeep of the dehesa is under threat. You’ll sometimes see a meadow with a solitary oak left standing; picturesque but troubling.

With nearly three-quarters of the Iberian peninsula now considered at risk, a belated fightback is underway. Local tree-planting groups have sprung up. Spanish institutions such as the petrol giant Repsol, and Santander bank, have joined largescale schemes to help save the traditional landscape and, by extension, the planet.

And many of our neighbours’ farms sport the blue plaques of the EU regional development fund, with details of grants aimed at regenerating the dehesa.

“You need to get planting,” said our friend Pláci as we walked among the oak trees. “Not for yourselves. For a hundred years from now.” So, in December, when the rains had softened the soil, we made a start by ordering 20 saplings from the cousin of our builder, Francisco.

We chose 10 holm oaks, whose small leaves resemble holly, and 10 cork oaks with silver-green foliage like miniature bay leaves. These grow a little more quickly, but we don’t expect to be producing cork for at least 35 years. The saplings were about a foot tall and cost a euro each.

They looked impossibly frail. If planted without protection, they would be destroyed by the deer that vault our walls at will and by our neighbour Antonio’s pigs and cows that often graze in the fields.

Pláci had the solution. Each day for a week he arrived in his van with three two-metre cylinders of chicken wire mesh, clipped together with the little pieces of wire used to attach the string to chorizo sausages. We secured them with steel rods hammered into the ground and rounded them off with lengths of barbed wire positioned at pig- and cow-head height. Around the base of each we pressed some extra acorns into the earth for good measure.

It will take 10 years for the saplings to be strong enough to fend for themselves, and another 50 before they take their place, fully fledged, in the timeless life cycle of the dehesa. We won’t be around to see that.

As we planted, Pláci had an idea: “You could give one each to the children to look after when they come to stay.” So we tied copper labels with their names on to the chicken wire, took pictures and slipped them into their Christmas stockings. A tree for life.

Peter Barron is an author for Frommer’s Spain. Follow his blog at adventuresinextremadura.com.