Venice is not everyone’s happy place. Wagner died there. DH Lawrence considered it “an abhorrent green, slippery city”. The Futurists detested it, declaring in a 1910 leaflet drop: “Let us hasten to fill in its little reeking canals with the ruins from its leprous and crumbling palaces. Let us burn the gondolas, rocking chairs for cretins, and raise to the heavens the imposing geometry of metal bridges and factories plumed with smoke.”

La Serenissima is still here – just – but no doubt the Futurists would be pleased with the decay that man has added to the city’s natural challenges. The cultural heritage preservation body Unesco, eager to put Venice on its endangered list, estimates that the waters it is built on will rise by one whole, unsustainable metre by 2100. A new €5 charge for day-trippers from next year will yield much-needed revenue for conservation projects, but is dismissed as just a sticking plaster by those who want rapid action on climate change threats as well as a reduction in tourist numbers.

Yet those who have come to Venice and left inspired are an integral part of its story. In his new book on the city, art critic Martin Gayford observes late 16th-century Venice becoming a tourist destination for the English. Much thought must have gone into his title, Venice: City of Pictures. Not only because innumerable books and chapters have been written on the city, but because this is not a guidebook so much as a chronology of Venice’s influence in art across the globe and through the ages.

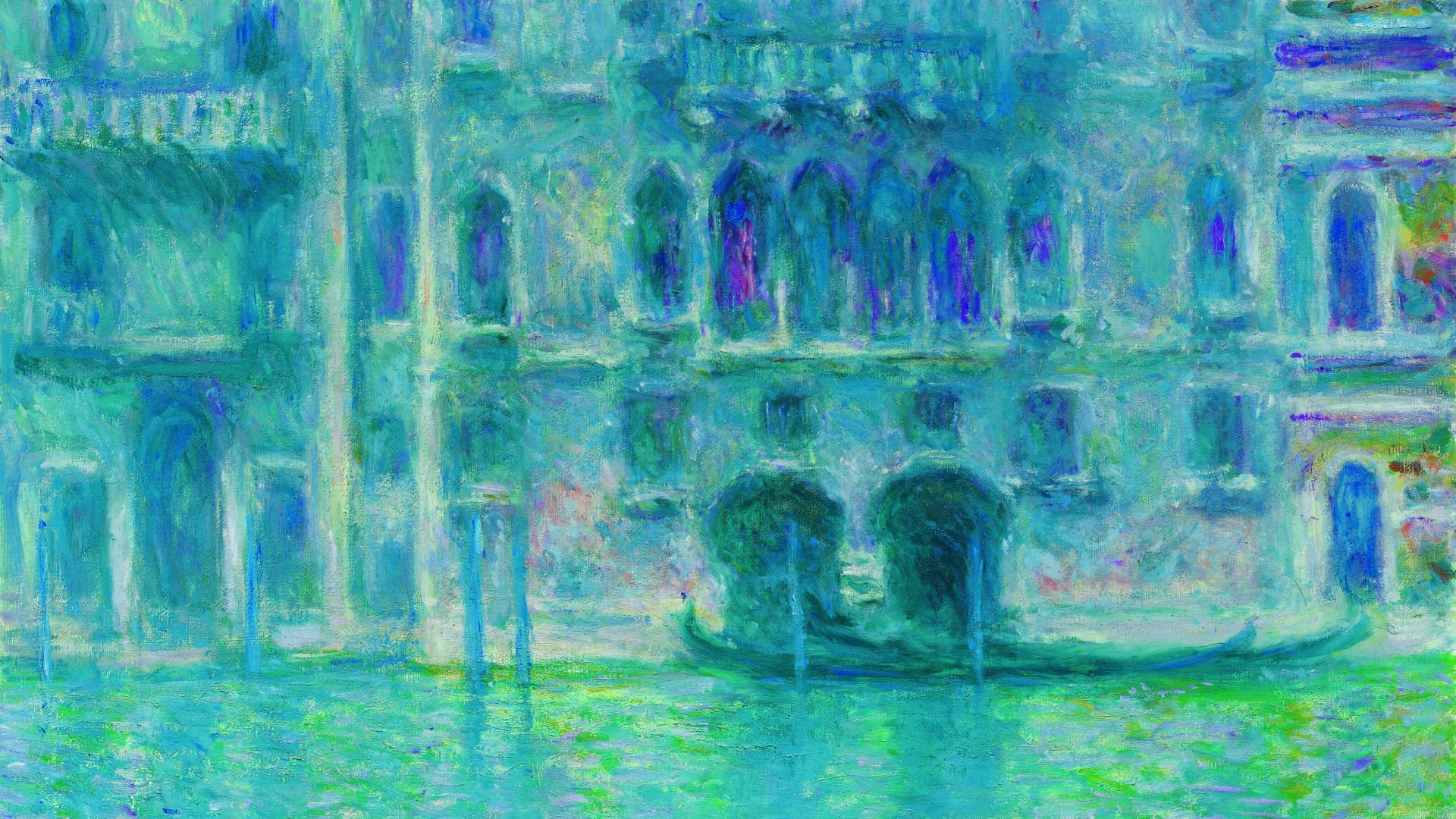

Works of art created in Venice are in galleries worldwide. Artists from other cities and countries have been drawn to Venice, absorbing into their own work its history and practices and taking something of the city’s art back to their own audiences. And there are pictures of Venice from Canaletto’s ingenious, upmarket postcards to a trillion amateur snaps.

The city has fought the elements for hundreds of years. Damp and floods are an immediate threat, and at the other end of the spectrum of danger, its wooden-framed buildings are vulnerable to fire. In earlier times, propelled by poor sanitation, plague repeatedly devastated the small population. Magnificent architecture grew in thanksgiving for deliverance from such attacks.

Sometimes other buildings or parts of buildings just plain collapsed. The architect Jacopo Sansovino (1486-1570) was forced to work for two years effectively without pay to cover the cost of repairs when the vault of the first bay of his magnificent Biblioteca Marciana, opposite the Doge’s Palace, fell down in the night. He protested that he had used weighty stone rather than wood, because it was more beautiful, and as a precaution against fire. Beating the odds when building in Venice is like a game of stone, paper, scissors.

Not a native Venetian, like so many arrivals into the city, Sansovino, who grew up between Siena and Arezzo in Tuscany, had to excel to be accepted. He was in good company, not least living alongside the phenomenon that, like fire and water, exerted an irresistible force on Venice: Pietro Vecello, the ambitious and prolific painter from Pieve di Cadore in the Dolomites, better known as Titian.

Titian, who arrived in Venice in 1513 with a self-written letter of recommendation, towers over the art of the mid-16th century and over Gayford’s book, his work magnetically attracting his contemporaries and successors through the centuries. Everyone wanted a piece of him. Particularly acquisitive was Alfonso, Duke of Ferrara, younger brother of the great collector Isabella d’Este of Mantua.

Titian, as Gayford describes entertainingly, was difficult to negotiate with, inclined to take on too much, to drive a hard bargain and to drop work in favour of a more appealing or lucrative project. But in Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-23), for Alfonso, he pulled out all the stops. (The cheetahs that draw Bacchus’s chariot are a reference to Alfonso’s private zoo, although the god is traditionally borne by tiger.) The picture, painted early in Titian’s long career, passed from Ferrara to Rome, then to Britain, and finally to London, where it is a star of the National Gallery, which acquired it in 1826.

It is one of many examples of work made in Venice but on display in another city, country or even continent, thanks to a vigorous and enthusiastic trade in art.

The art market, says Gayford, was born in Venice. The city already ran on trade, and also there was growing interest in individual artists. In this way of looking at art, however, it ran behind Florence. There, the lives of artists were being put on record, notably by artist and chronicler Giorgio Vasari, while in Venice Marcantonio Michiel (1484-1552) began listing who made what for whom, concentrating on the painter rather that the artwork, but omitting titles, so making it difficult to identify pictures later.

Attribution fuels the art trade. A work by Giorgione is, points out Gayford, worth more by far than one that is “after” or “school of”. And putting a value on this crucial, and lucrative difference can be traced back to Isabella d’Este, Michiel and other connoisseur-collectors.

While Titian cast his long shadow over contemporaries and successors alike, young pretenders were pushing their way on the art scene that he dominated for six decades. Jacopo Robusti was, unlike so many of those who made an impact on the city, born in Venice, the son of a dyer, hence his nickname Tintoretto. But he was also known as Il Furioso, such was the speed and passion with which he hurled himself at his dynamic painting. Invited in 1564 to submit sketches for a ceiling painting in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, he wrong-footed other shortlisters, including Paolo Veronese, by producing and installing a full-sized work. There followed a full cycle of paintings which Gayford describes as “one of the greatest one-person exhibitions by anyone in the world”.

New arrivals to Venice, who step out of the station or off a boat for the first time, can feel like actors on a set. The theatricality of the city is vividly demonstrated by another incomer. Paolo Caliari, nicknamed Veronese after his native city 120km away, was taken to task for piling too many eye-catching characters into one religious scene. He resolved that theological spat by retitling The Last Supper.

Today it is the Supper in Emmaus that, like the same artist’s vast The Wedding at Cana (1562-63), graces the Louvre in Paris, thanks to the collecting spree throughout Italy by Napoleon’s forces. The Wedding at Cana on view in the space for which it was commissioned, the former monastic refectory in San Giorgio, is a meticulous and convincing reproduction. Gayford writes particularly engagingly about the deft Veronese and his magnificent, populous scenes in a chapter entitled The Case of the Painter and the Feast.

Veronese was not alone in creating breathtaking effects. A little off the beaten track in the church of St Pantalon on the Dorsoduro, Giovanni Antonio Fumiani spent 24 years painting a single ceiling with a massive cast, intricate props, towering columns and giddying staircases that zoom into the stratosphere. Some 40 years later, Giambattista Tiepolo similarly challenged the neck muscles of his admirers with more stairs, tumbling figures and soaring skies, in the Gesuati. “This is a picture about above-ness,” explains Gayford, who says of Tiepolo: “His ceiling paintings are the nearest thing art has to offer that compares to flying high up in the sky.”

The Venetian taste for theatre spilled over into a new-fangled art form that was all the rage in the early 17th century – opera. Here was another medium which seeped like watercolour across the western world. An appetite for spectacle and multi-sensory overload was fed with ingenious stagings of stories in song, and while these entertainments had taken place in the private rooms of the wealthy, the Teatro San Cassiano became the first theatre in the world to stage opera to the general public. Ingenious designers conjured impressive effects with moving scenery, delightful trickery that would be emulated Europe-wide.

Theatre set painter turned cityscape painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), better known as Canaletto, knew all about special effects. While the accuracy of his preparatory drawings indicate the use of a camera ottica or camera obscura, once a canvas was before him he nipped and tucked to create tighter and more dramatic views of Venice. Trying his luck in London, early success gave way to a loss of interest in his vivacious scenes, but his vision of Venice is one recognised worldwide.

The world knows its Mozart too. But without Venice, there may have been no Don Giovanni, no Le nozze di Figaro, no Così fan tutte. Mozart’s librettist Lorenzo da Ponte was an enthusiastic partaker in the masked antics of Venetian society who adopted the costumes and masks of the stage. Even Puccini’s Turandot can be traced back through a musical labyrinth to Venice and a play in 1762 at the Teatro San Samuele.

After a lifetime of visits and study, in this impressive volume, Gayford sums up Venice’s gift for embracing its past and honing its future. In a persuasive defence of the now unfashionable work of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo he observes that “he and his work are like the city itself. Venice, too, can seem outmoded, quaintly irrelevant to the modern world. Then, suddenly, you realise that it is not.”

Venice: City of Pictures by Martin Gayford is published by Thames & Hudson at £30