The photograph shows a poster I discovered in mid-August in Olšanské Square, Žižkov, Prague. A working-class area with a fascinating mix of late 19th-century buildings, dive bars and Communist-era blocks, Žižkov has always been the home of the counter-cultural scene in the Czech capital. In December 1988, Václav Havel gave an opposition speech in the district’s Škroupovê Square, the first permitted assembly during “normalisation”.

In recent years, Žižkov has become a little like Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg in the 90s – arty-edgy and open-minded, but slowly creeping towards a bourgeois takeover as old buildings are renovated, rents leap upwards, and the new money wants to transform the district into a rival for its more refined neighbour up the hill, Vinohrady.

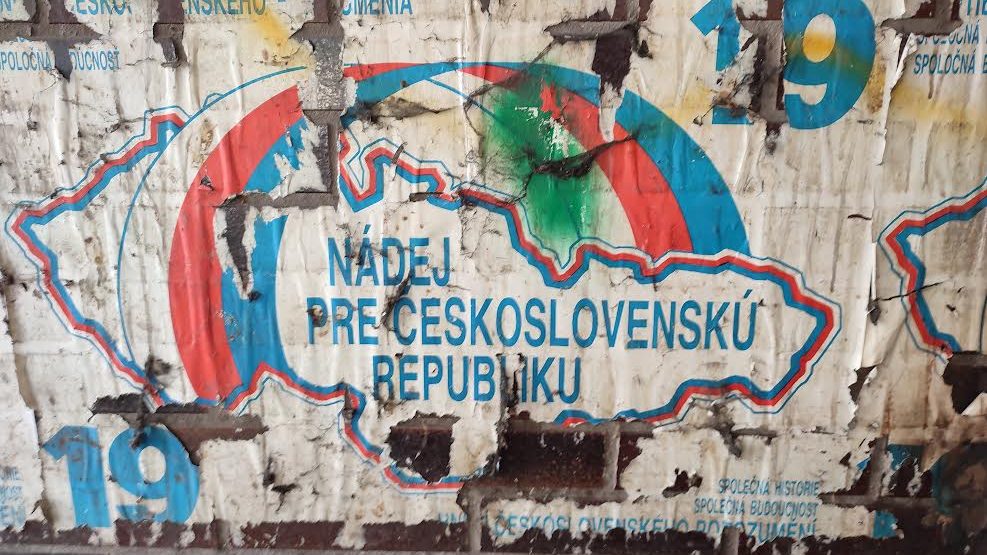

Part of the current renovation includes improvements for a huge block of flats in Olšanské Square. The first step was to remove a fruit and veg stand that had been run for years by a Vietnamese family. The tin and plastic kiosk was dismantled in hours, and when I stopped for a look around, I noticed an original brick wall behind, bearing the poster pictured here.

As Charles University historian, Marek Ďurčanský, told me: “It is significant that you found the poster in Žižkov. At the beginning of the 90s, Žižkov was not a trendy and lively quarter like it is today, but more an internal periphery. Some places retain the mood of old Žižkov, but step by step they are disappearing. The surroundings of the poster are just such a place.”

According to dates on adjacent gig-promoting posters that had also survived, I worked out that this one comes from April 1992, when the kiosk must have gone up.

The poster speaks of “hope for a Republic of Czechoslovakia”, urging the two states to stay together with their “shared history, shared future” and “mutual understanding”. It is two and a half years since the Velvet Revolution. Václav Havel is the dissident playwright turned president of Czechoslovakia. In early 1992, he repeated his opposition to the breakaway of Slovakia that was being championed by Slovak nationalists. Indeed, in a September 1992 opinion poll, only 37% of Slovaks and 36% of Czechs wanted to split, but the decision did not go to a public referendum.

Not wishing to oversee the divorce he opposed, the president resigned. (He would be re-elected as the first president of the Czech Republic in January 1993.) The dissolution of Czechoslovakia finally took effect on December 31 1992.

“It’s funny that the poster was revealed just now, more or less 30 years since the split,” Ďurčanský said. “The poster reminds us about a strong part of Czech and Slovak society who were keen to keep the common state. But they were not as loud or as powerful as the ones who wanted to separate.”

With Slovakia emerging from an election in which a populist returned to power, the reappearance of a poster championing the country’s former identity is a reminder of the ever-changing nature of nationhood and the fact that a powerful plea can be reduced to the paper on which it is written.