So 2025 is upon us, and what a year it promises to be. With progressive governments in place across the globe seeking to work together under leaders of intelligence and humility, we can look forward to… oh, haaaaaang on.

OK, so it seems that in 2025 we’ll need mechanisms in place to keep us functioning and sane again and what better mechanism is there to achieve that than getting stuck in to a really good book? Thank goodness, then, that it seems plenty of those are coming down the pipe in the next 12 months.

I say “seems” because previewing forthcoming books is a bit of an odd thing to do, like examining football matches months before they happen or analysing the weather for the coming summer. It is tricky enough writing about books that have been published, let alone those that are in some instances still effectively just press releases, half a page in a publisher’s catalogue or even a file on someone’s MacBook.

So, given the parlous state of the world and the fact that we have just embarked on what always feels like the longest and most miserable month of the year, before we get to the new stuff I feel it might be helpful to point you towards one solid gold, copper-hulled prescription for literary wellness: a good dose of PG Wodehouse.

The Jeeves and Wooster books, the Blandings series, the Ukridges and Psmiths, there are dozens of titles and series to choose from to experience the best of bookish escapes, one in which the writing is flawless and there is at least one guaranteed laugh on every magnificent page. If I have to pick one to get you started, tell The Code of the Woosters I sent you. You won’t regret it.

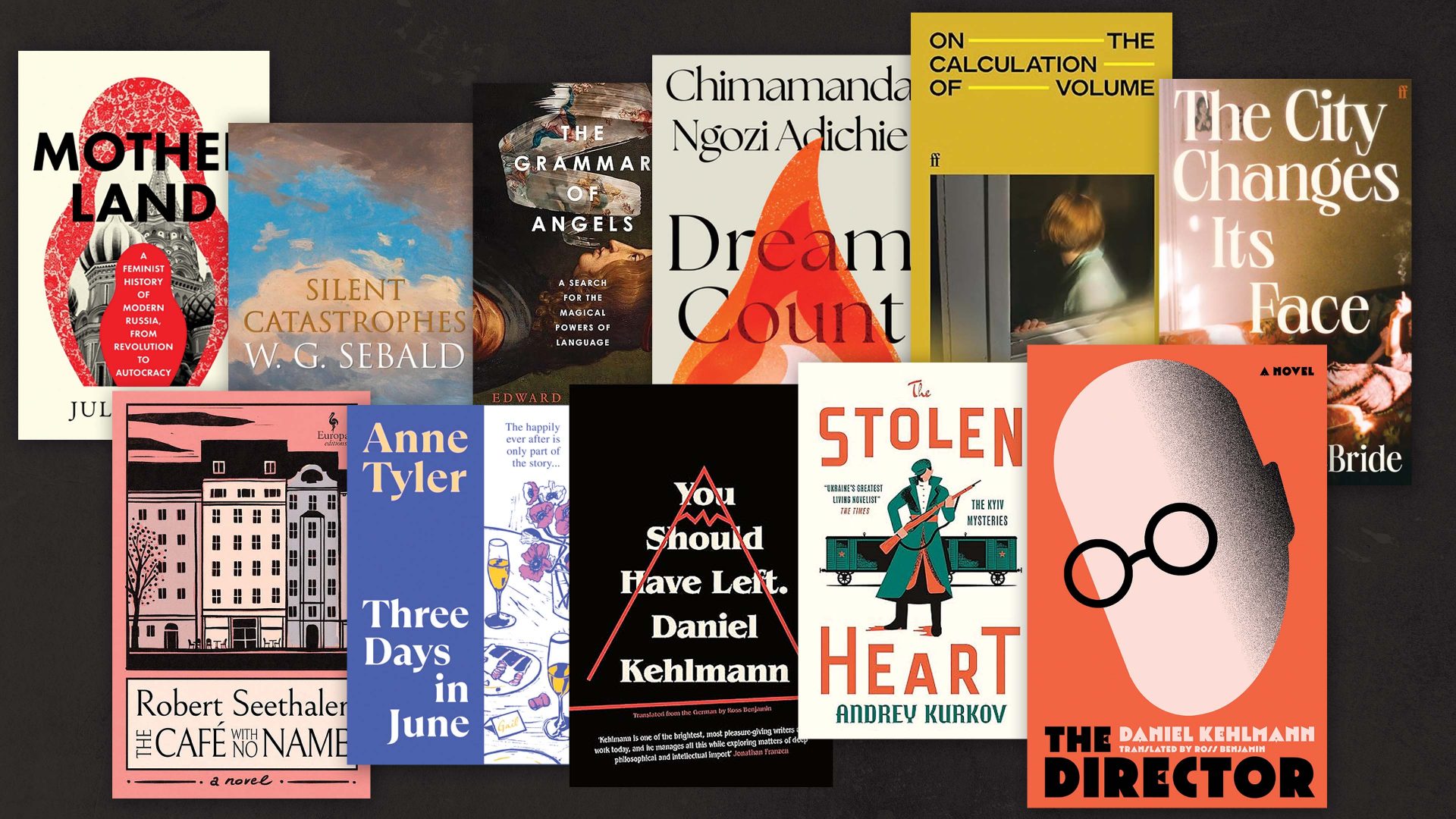

From an author who has been dead for half a century to some who are not only very much alive but also currently outpacing Wodehouse in the productivity stakes by some distance, here are some forthcoming titles that stand out as having a decent chance of enhancing your reading year.

We don’t have to wait too long for The Grammar of Angels: The Search for Magical Powers of Language by Edward Wilson-Lee (William Collins, £25), which is published later this month. Wilson-Lee has written the story of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who in 1486 and aged just 23, gamely announced he was prepared to defend 900 different theses on religion, philosophy, natural philosophy and magic against anyone who would care to argue.

He wrote up his ideas in a book, Oration on the Dignity of Man, that became the first ever to be banned by the church, before dying in mysterious circumstances at the age of 31, possibly the victim of deliberate poisoning. When he died, Mirandola was working towards inventing a form of language so powerful the speaker could exercise complete control over whoever was listening.

With his A History of Water and The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books, Wilson-Lee has established himself as a wonderful chronicler of stories too oblique for less adventurous writers and The Grammar of Angels promises to be one of the non-fiction highlights of the year.

Also this month, 24 years after the death of its author comes Silent Catastrophes: Essays in Austrian Literature by WG Sebald (trans. Jo Catling, Hamish Hamilton, £25). Sebald was one the finest and most enigmatic writers of the European 20th century, producing the bewilderingly inventive novel Austerlitz and straddling fiction and non-fiction with his East Anglian travelogue The Rings of Saturn.

Silent Catastrophes combines for the first time in English two books of literary criticism in which Sebald discusses the Austrian writers he admires most, from Joseph Roth to Peter Handke. You won’t need a particular knowledge of, or even interest in, Austrian literature to appreciate Sebald’s writing here.

Next month brings a book that feels long overdue. In Mining Men: Britain’s Last Kings of the Coalface (Chatto & Windus, £22) Emily P Webber, who grew up in a mining community, tells the story of the miners, who in the middle of the 20th century numbered a quarter of a million but worked in an industry that had been all but obliterated by the turn of the millennium. Combining detailed archival research and first-hand accounts of men who spent their working lives deep underground, Mining Men promises to be a definitive piece of social history.

It is 36 years since Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence launched a torrent of tedious Brits-move-to-sunny-parts-of-Europe-and-goodness-me-aren’t-the- locals-adorable copycat titles. Travel literature has moved on considerably since then, hence I am actually looking forward to April’s Angels in the Cellar: A Life Rewritten in a French Vineyard by Peter Hahn (Little Toller Books, £22). Hahn moved from England to the Loire Valley following a severe mental health episode, took on an ancient little farm and began producing small-batch organic wine. Angels in the Cellar is Hahn’s chronicle of a year in the vineyard with ruminations upon the land, winemaking, life and the turning seasons.

It’s not out until June but Julia Ioffre’s Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, from Revolution to Autocracy (William Collins, £25) looks to be an exciting and original take on the nation’s path since the 1917 Revolution. Ioffre was seven years old when her family left Russia for the US and when she returned in her mid-20s the changes in the space of barely two decades astounded her, not least in the place of women in Russian society. To examine why, she delves into the national story from the perspective of its women, from Lenin’s lover Inessa Armand to Pussy Riot and Yulia Navalnya. Drawing on her own family history too, Ioffre’s book promises to be an absorbing take on an important and too-long overlooked aspect of modern European history.

To fiction now, starting with translated fiction from Europe and one of the most consistently innovative writers in Europe today, the German author Daniel Kehlmann. The author of 14 novels and four stage plays, Kehlmann seems able to succeed in any genre that takes his fancy. His 2016 novella Du hättest gehen sollen, translated into English as You Should Have Left, is one of the most frightening works of fiction I have ever read, while 2017’s magnificent Tyll, based on the mythical jester Till Eulenspiegel, has sold more than three quarters of a million copies in Germany alone.

In May comes The Director (Quercus, £22), translated by his long-time collaborator Ross Benjamin, which immerses itself in the life and world of the visionary Austrian film pioneer GW Pabst.

When the Nazis came to power, Pabst was filming in France and fled to Hollywood where he failed to make any impression at all, eventually finding himself back in Austria. Goebbels made insistent overtures, keen to coerce the director into his state-run cinema operation churning out Nazi propaganda, leaving Pabst to weigh up his opposition to fascism with his need to create art. It is a terrific concept and Kehlmann is the perfect writer to bring to life.

Ukraine’s finest contemporary novelist Andrey Kurkov returns in February with The Stolen Heart, the second in his series of Kyiv-based thrillers set against the background of the Russian Revolution (trans. Boris Dralyuk, Quercus, £20). Its predecessor The Silver Bone was longlisted for the International Booker, and here his detective Samson Kolechko finds himself at the heart of a multilayered narrative involving the abduction of his fiancée by striking railway workers, a deadly tram crash and some stolen meat of initially questionable significance. Impeccably researched and inspired by real events.

I’ve been a fan of the Austrian writer Robert Seethaler ever since Charlotte Collins’ wonderful 2015 translation of his novella Ein Ganzes Leben (A Whole Life), one of the most brilliant evocations of the passing of time you’ll read, so I am excited about the arrival next month of The Cafe with No Name (trans. Katy Derbyshire, Canongate, £16.99). Set in 1960s Vienna, the novel follows the fortunes of the staff and customers of a newly opened cafe, tracing their interactions, friendships, stories and secrets. I am really looking forward to this one.

Spring brings the long-awaited UK release of the first two volumes in the Danish writer Solvej Balle’s septet of novels On Calculation of Volume. Three years ago Faber & Faber beat off strong opposition to win a six-way auction to publish the first three books in Balle’s series – 30 years in the making – and the first two, On the Calculation of Volume 1 and 2 (both trans. Barbara J Haveland, Faber & Faber, £12.99), are published together in April.

The winner of the 2022 Nordic Council Literature Prize, On the Calculation of Volume 1 follows antiquarian bookseller Tara Selter as she wakes every day to find herself in the same Paris hotel room on the same day, November 18, following the same routine, knowing that she is somehow trapped in time. The first book tracks her first year of November 18s while in the second volume, she finds her routine changing for the first time, boarding a train as the season changes.

“A startling exploration of profound questions about language, human connection, and time,” according to the New Yorker, these much-anticipated books originally published in Denmark by the author’s own small press promise to be among the most sought-after reads for Europhilic English language readers this year.

The Irish writer Eimear McBride shot to prominence with the idiosyncratic and hypnotic prose style of her 2013 debut A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, winning the Women’s Prize for Fiction, followed three years later by The Lesser Bohemians and in 2020 by her third novel Strange Hotel. It’s fair to say the arrival next month of The City Changes its Face (Faber & Faber, £20) is keenly awaited by her considerable fanbase.

It’s 1996 and two lovers, a 40-something man and a woman half his age, in a Camden Town flat look back over their intense two-year relationship. Written in McBride’s characteristically original style, this promises to be well in the mix come awards season.

Other titles to look out for include the first novel in a decade from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Dream Count (Fourth Estate, £20), a meditation on love and happiness in the stories of four women set between the US and Nigeria, out in March, while February brings what Anne Tyler says could be her last novel, Three Days in June (Chatto and Windus, £14.99), an examination of love and the passing of time set on the weekend of a wedding.

August brings RF Kuang’s follow-up to the phenomenon that was Yellowface, Katabasis (HarperVoyager, £22), which is billed as a love story about two rival Cambridge academics on a bizarre rescue mission to hell to retrieve the soul of their adviser, while the spring brings a new novel from Dublin’s Colum McCann, Twist (Bloomsbury, £18.99), a literary thriller set on a cable-repair vessel off the coast of Africa that comes with endorsements from the likes of Elif Shafak, Kevin Barry and Salman Rushdie.

Clearly, whatever else might happen in the world this coming year we won’t be going short of absorbing reading matter. So don’t worry. We’ll get through this. With books.