Sergio Leone thought in widescreen. “In the future,” the great director once said, “I see gigantic stadiums. Each big city will have only two or three cinemas, but they will be huge. They will seat 10,000, 20,000 people – the opposite of venues being broken up into 10 small auditoriums.

“The screens will measure 50 metres, and certain films will be appropriate to be shown on them,” he continued. “The sensation you get from a huge screen with stereophonic sound, 20,000 people surrounding you, buzzing with conversation, living and pulsating with the shows they are watching – that can never be replaced by a television-sized screen, however big it is.”

Leone was a big man whose talk and ambitions were equally huge. In Sergio Leone: By Himself, a sublime and sumptuous (and appropriately sized) new book of Leone interviews and articles, his biographer, Christopher Frayling, describes him as “in some ways a Falstaffian figure – ample of girth, bearded, built like Orson Welles.”

When Frayling meets him for an interview in a London hotel bar, “just before the usual pleasantries, Leone did something I had never seen before. He picked up a large bowl of salted cashew nuts, transferred the nuts to his left hand, and emptied the entire contents into his mouth in one go, some of the cashews falling into his beard. He then greeted me, with a broad smile and a knowing twinkle in his eye, and we took the lift to his room while he munched.”

The maestro also indulged “a passion for double corona cigars (‘physically and sensually they suit me perfectly’), a taste for full-bodied Brunello di Montalcino wine and a prodigious appetite for Roman and Neapolitan delicacies; a deeply resonant voice – ideal for telling heroic or tall tales, or for making grandiose, allusive statements about his work.”

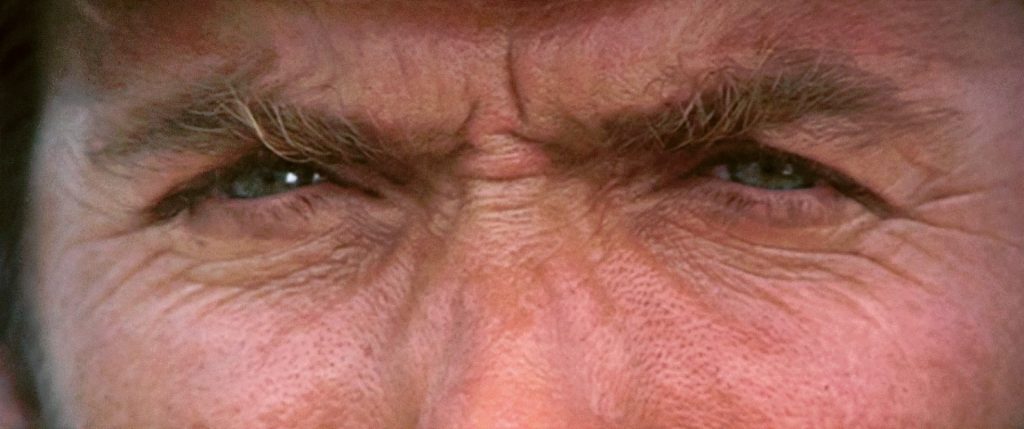

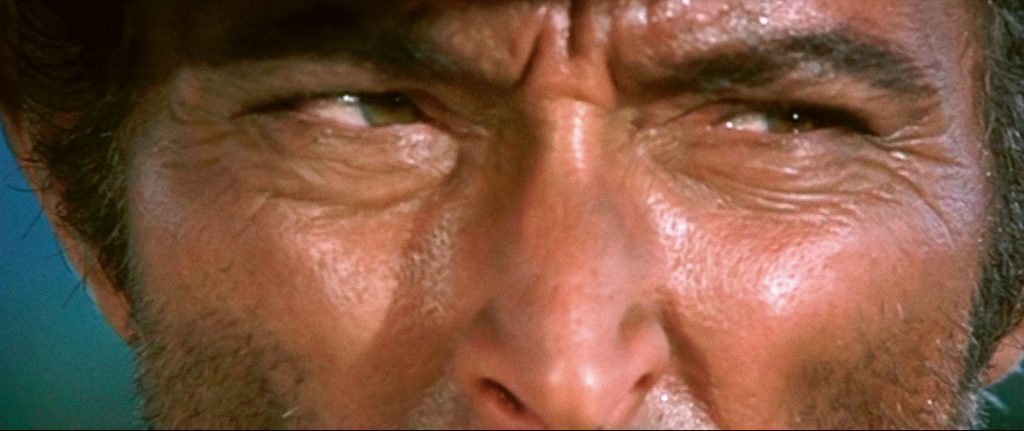

His vision, of course, was vast – visually magnificent creation myths of an early America populated by warriors for who the dream was already dead. Giant close-ups and sweeping long shots studded the typical Leone film, which he defined as the “picaresque epic told spectacularly in a mixture of fairytale and reality.” Epic heroes, epic vistas, epic betrayals, epic disenchantment.

Leone began his career as an assistant on a small-scale masterpiece, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. More influential to his future would be the American proto-blockbusters Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur, on which he worked at Cinecittà in Rome.

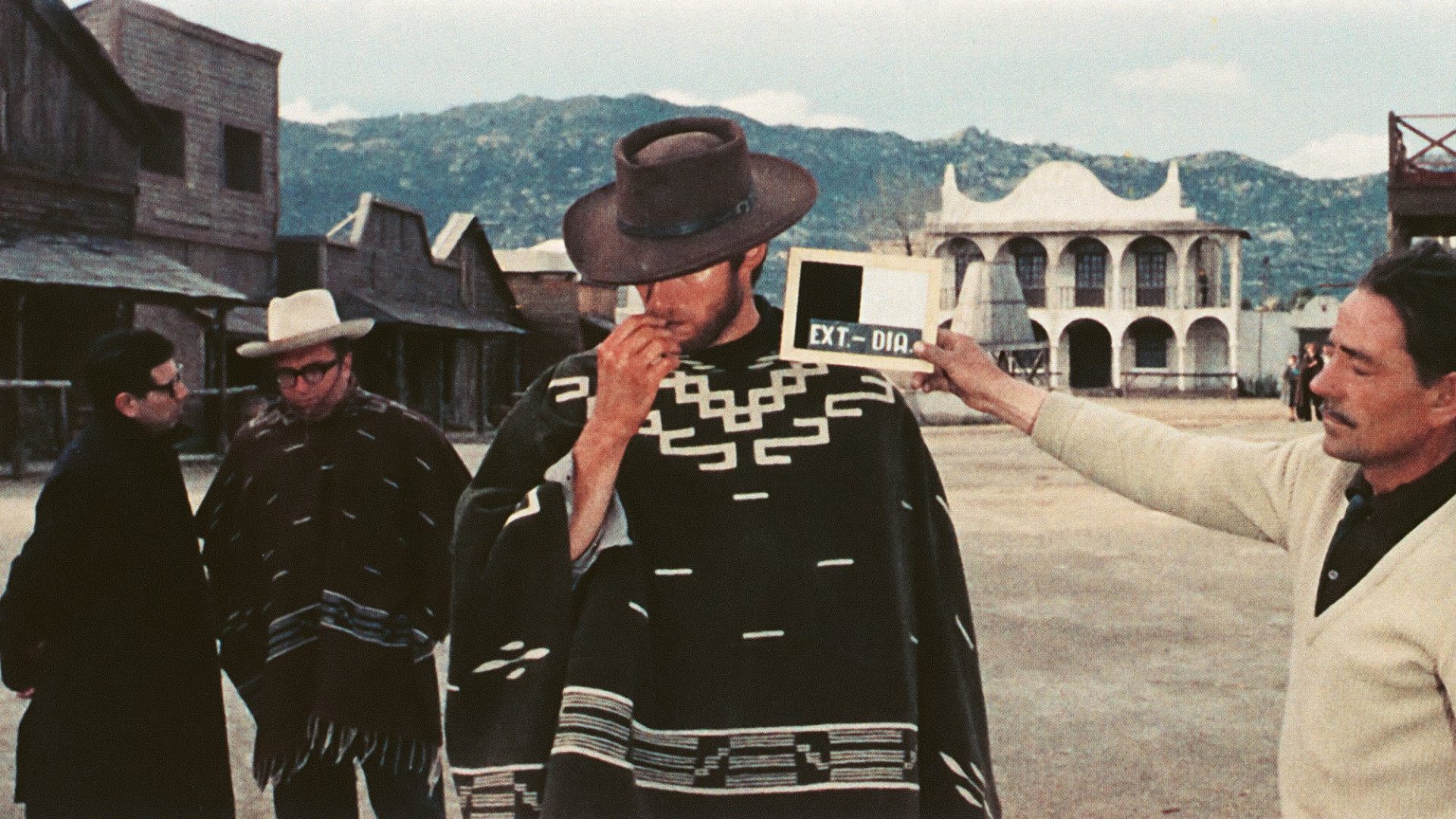

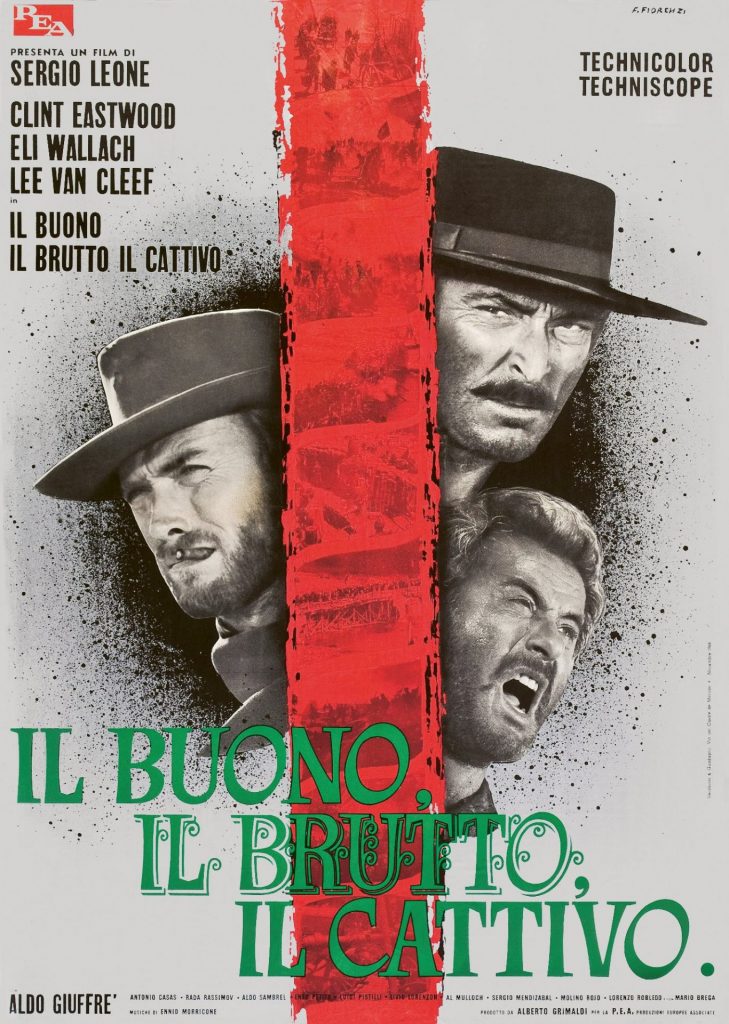

His vision took shape in the tightly budgeted spaghetti westerns A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965), after which, he said, “when my rating on the market had freed my neck from the producer’s noose once and for all, I started making films that were more complex and monumental… The reality is that epic cinema forces you to broaden the narrative scope and worry about the details almost obsessively.” He then reunited with Clint Eastwood to conclude the Dollars trilogy with The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966), which Leone fondly remembered as “an extremely expensive film, very long and over-elaborate, decidedly monumental. It was a pleasure to film, a joy even.”

The magisterial Once Upon A Time In The West (1967) took Leone to Monument Valley, Arizona, the sprawling playground of his hero John Ford, for “a ballet of the dead, a dance of death” that sought to bury not just the western’s stereotypes – “the whore with a heart of gold, the romantic bandit, the killer who wants to get on in the world of business, the businessman who fancies himself as a gunfighter” – but the genre itself.

A near-three-hour film was disdained by the studios for its length, and Leone spent much of the next 17 years trying to finance its pair. When Once Upon a Time in America finally emerged in 1984, it came at four hours long and shared its predecessor’s elegiac feel. Leone called it a “dream journey” through “a land suspended as if by magic between cinema and epic… where John Dillinger dies under the neon sign of the Biograph Cinema in Chicago and where Chaplin and Fairbanks electrify the crowd on Wall Street. Here, violence becomes almost an abstraction and the hero is unaware of what Fate holds in store for him.”

Leone never made another film, but he was always dreaming on the widest canvas. At the time he died of a heart attack in 1989, at the age of 60, he had three epic projects on the go.

There would have been a civil war spectacular with Richard Gere and Mickey Rourke chasing buried treasure amid the carnage and cruelty, a second world war love story (“a lost love, lost in hell”, Leone said) with Robert De Niro as an American journalist trapped in the siege of Leningrad, and an intriguing TV mini-series that followed a single pistol and its owners through the evolving American west.

His frequent collaborator Fulvio Morsella said: “Fifty years earlier, he would have been a great maker of lyric operas… he had that sense of the visual image, the sound and of course the spectacular. He had a theatrical sense of a scene. Unlike other great film-makers who stayed with the small, he would always make it big.”

Sergio Leone: By Himself, compiled by Christopher Frayling, is published by Reel Art Press